Photobook Review: My Grandfather Turned Into A Tiger... And Other Illusions by Pao Houa Her

-

Published13 Feb 2024

-

Author

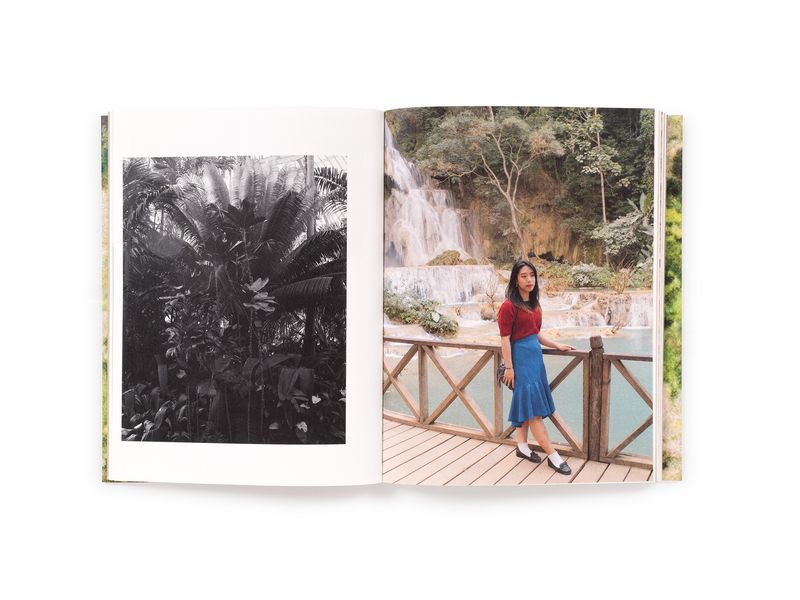

Somewhere between Laos, Minnesota and Northern California, Pao Houa Her’s work shapes a mythology of diaspora and displacement, with plastic landscapes coming to life and waterfalls turning into static backdrops.

“Can I tell you the story?", Pao Houa Her asks. "Back in late 2015, my great-aunt was dying with cancer. She was the youngest sister of my grandfather who I never met. I asked her to tell me about him. My grandparents had just got married, she said, and in 4 years they had 4 kids. When General Vang Pao came and asked the men in their village to fight on behalf of the Americans, my grandfather felt obliged to go. He left to fight, and he stepped on a mine. So he died and he turned into a tiger. He turned into a tiger and came back in my grandmother’s village to stay with her. The villagers and her were really scared of this tiger that was my grandfather, and people believed the story so much they would ostracize my grandmother. For a while she was isolated with the tiger. She became very sad, and asked the tiger to leave”.

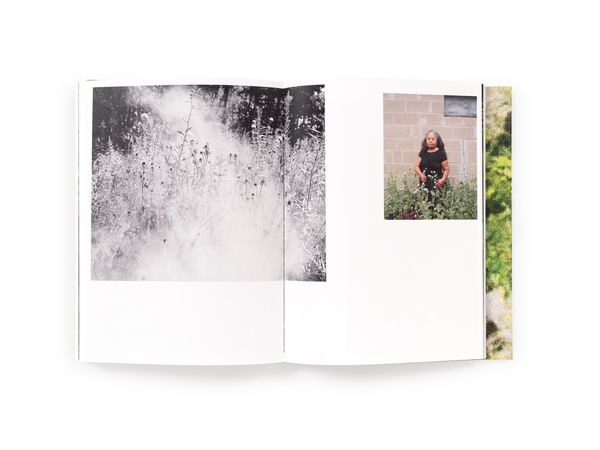

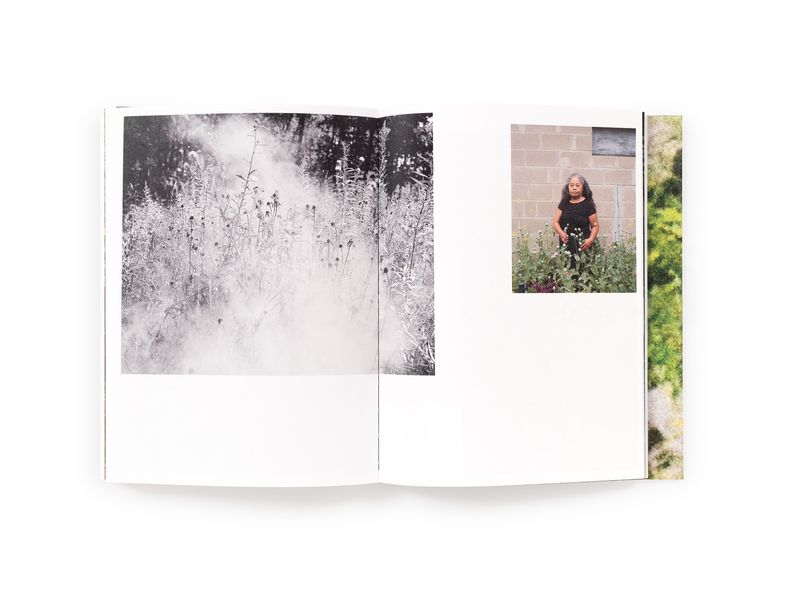

The tale giving My grandfather turned into a tiger… and other illusions its title is rooted in oral tradition. Its hallucinatory narrative has passed on through generations, carried by words different and similar at the same time. This and five more stories, originally belonging to separate series, weave the non-linear plot of Pao Houa Her’s first monograph published by Aperture. There are no chapters, nor captions guiding us through them: it’s as if we were listening to someone telling a story that started long before we came. We need to catch up with codes and tropes, to figure out connections and fill voids. “I’ve always thought of my practice as writing a story, or a letter. Every image is either a paragraph or a word or a punctuation mark. As they come together, they strengthen each other”, she says.

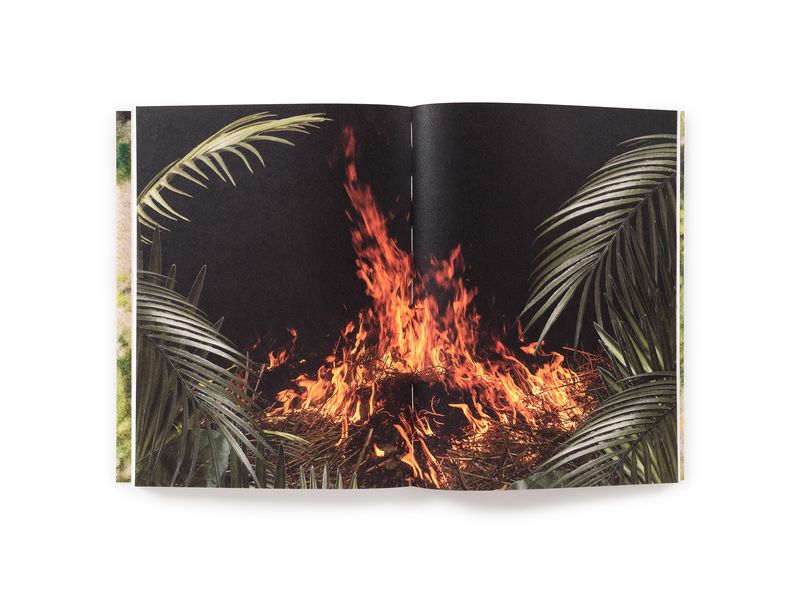

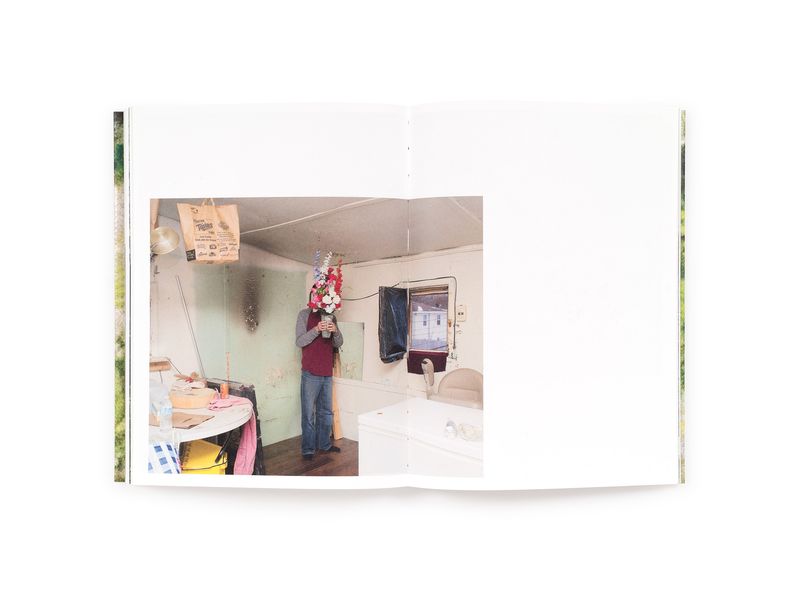

Pao Houa Her's images shape a story that is many stories at once. It is made of facts that haven’t been recognized as such, and need fiction to become real: it is the case of the elder Hmong men who served in the Vietnam War without ever having been acknowledged by the United States, here portrayed wearing uniforms and medals in a formal, military stance. It is made of fictional stories that sneaked in the everyday and became tangible: the tiger living by the side of Pao’s grandmother is as real as the fraudulent investment scheme that promised Hmong elders a new homeland, which never came. It is as real as the Hmong immigrants cultivating Marijuana in the Californian region of Mount Shasta, as the profiles of Hmong women on American dating apps, and as the flowers that recur and tie together this cosmos of characters, of poems and lies, where plastic landscapes come to life and waterfalls are turned into static backdrops.

Mythology is a place where non-humans, gods, and people act on the same level. They seem to live in separate, though connected parallel narratives, constantly moving from one backdrop to the next. Orality is at the core of this multiplicity: as many different voices tell and re-tell stories, they transfer knowledge that grows as it mutates. Pao Houa Her’s mythology of diaspora and displacement, of illusions of home and claims of belonging, seems to carry visual markers of some sort of orality, too. It has repetition and redundancy. It has a kind of formulaic character - those linguistic structures that recur to ease memorization. Characters, places, props and symbols keep circling. They disappear then they come back, slowly stratifying and consolidating meaning.

A photograph of a kid dressed in traditional Hmong clothes is printed on the cover, then repeated several times: it’s the same identical photograph, but every time the girl is someone else. She is one of Pao Houa Her’s cousins, and all of them at the same time. “It’s an image my grandmother had commissioned as she left for the US, having to leave the grandchildren she raised in Laos”, she recalls. “A photographer came with their portrait studio and made this photograph for my grandmother to remember her. It was the only photo that she carried with her. After she had a stroke and was completely immobilised, the photograph kept staying with her, the only one in her room and in every house we moved to. It calmed her down. When my grandmother died, I asked my father if I could keep it. One Thanksgiving my cousins came over and saw the photograph sitting in my living room. We talked about it, and I jokingly said I would put all of their faces in it so that we all could be my grandmother’s favorite grandchild. And I did: for Christmas I gave them ten copies of the photograph, with their faces replacing the original. At first it was this joke, but then it became something else. Because suddenly we were in this photograph that we knew our mother had commissioned. This cousin who my grandmother loved… we all became her at some point. It became this illusion for us all, right?”

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes’ evokes a photograph he found of his deceased mother as a kid, standing in a garden. He describes it without showing it. The Winter Garden photograph, so he calls it, is the image he holds on to, it is at once the essence of his mother and the essence of photography. The photograph of Pao Houa Her’s cousin seems to have been just as vital for her grandmother. Here, not only do we get to see it - it is proposed to us multiple times and we see it changing, we see it altered and falsified. Its aura is somehow both profaned and intensified: all the cousins can be that cousin. What is personal and unique can reach many. The absurd presence of a tiger, an obsession with fake flowers, an American military suit - scattered symbols can all reach the guts of a people and shape a mythology for its fragmented, its displaced identity.

Making their entrance into the book at quite an early stage, the manipulated portraits of the cousin(s) seem to state that there is no such thing as truth. There are lies - or better, illusions - and there are many truths that cooperate to create a story. “Historically the idea is that the camera always renders the truth, right?” Says Pao Houa Her. “The way in which I think about the camera is that photography is a truth - but it’s not the complete truth. In a lot of ways, it is a lie. The photographer gets to make the decisions. What image the world gets to see, and what image it doesn’t get to see. That’s very far from truth. And my truth is very different from somebody else’s truth”. This place we are looking at, this home so intensely longed for, is both Laos and America and none of them at the same time. It is the search for a place that never came, it is the crossing of altered memory and expectations, it is a way to animate loss and give it a meaning, if not a purpose. Ultimately, it is a statement of the importance of stories as realities we live by. And to the idea that in this, words aren’t necessarily needed. “It’s the idea of love, and loss, and desire. Allusion, disillusion. You know that my grandfather turned into a tiger, and it is your job to go into the images and try to decipher what are the players, and how this happened. That for me became the task of storytelling in a non-linear form”.

--------------

My grandfather turned into a tiger... and other illusions is published by Aperture

Format: Paperback / softback

Number of pages: 124

Number of images: 80

Publication date: 2024-01-23

Measurements: 8.5 x 6.7 inches

ISBN: 9781597115650

--------------

All photos © Pao Houa Her

--------------

Pao Houa Her (b. in Laos, 1982) is a Hmong American artist and assistant professor in photography and moving images at the University of Minnesota. She holds an MFA in photography from the Yale University School of Art (2012) and a BFA in photography from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (2009). Her’s work has been presented as a solo exhibition at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis in 2022–23 and she was included as part of the Whitney Biennial in 2022. In 2023, Her was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. She is represented by the Bockley Gallery, Minneapolis.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based in Italy. Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.