Photobook Review: Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography

-

Published30 Nov 2023

-

Author

How do you reconcile the conflicting powers that go into making a photograph? How do you balance power and control manifested by the person photographed, the photographer, the viewer of the image, the gallery, newspaper or archive it shows in?

The authors of Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography describe it as a ‘messy book’, made in a ‘disorderly way’ through workshops, exhibitions and seminars in which the five authors had different ways of thinking about what collaboration is and how it can be organised.

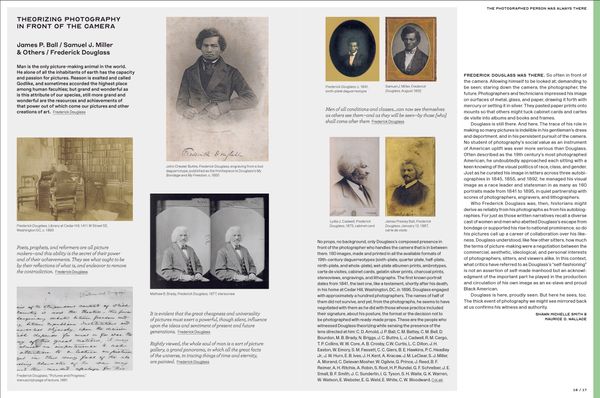

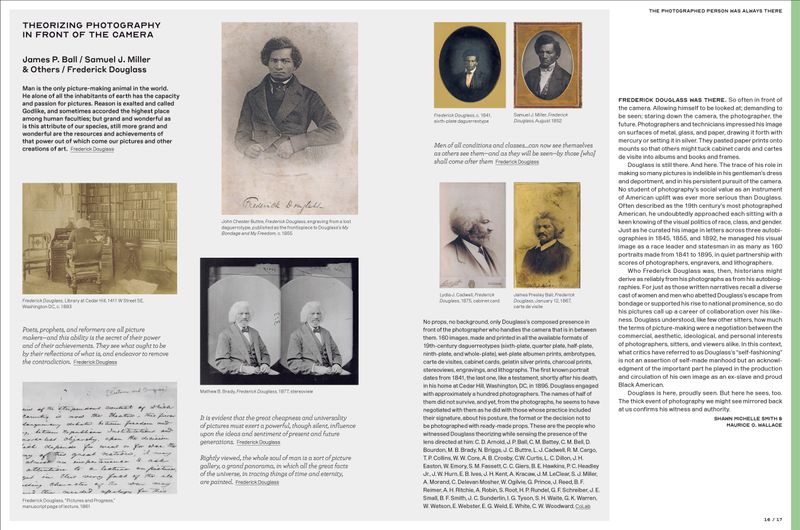

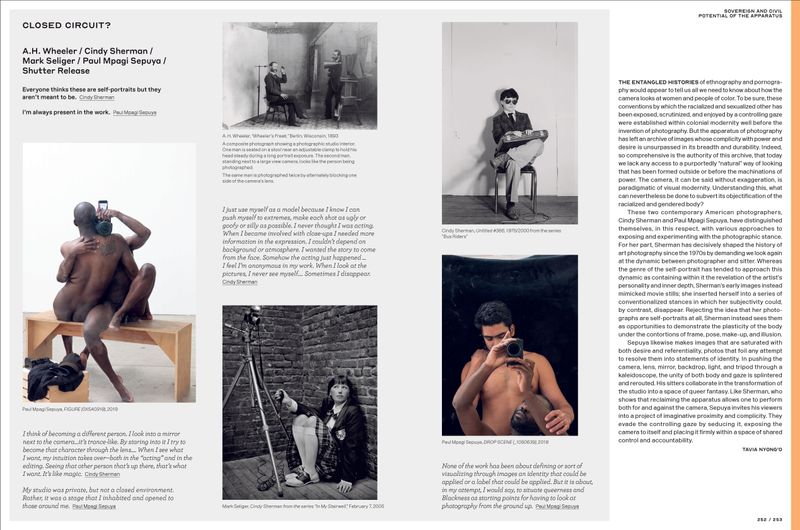

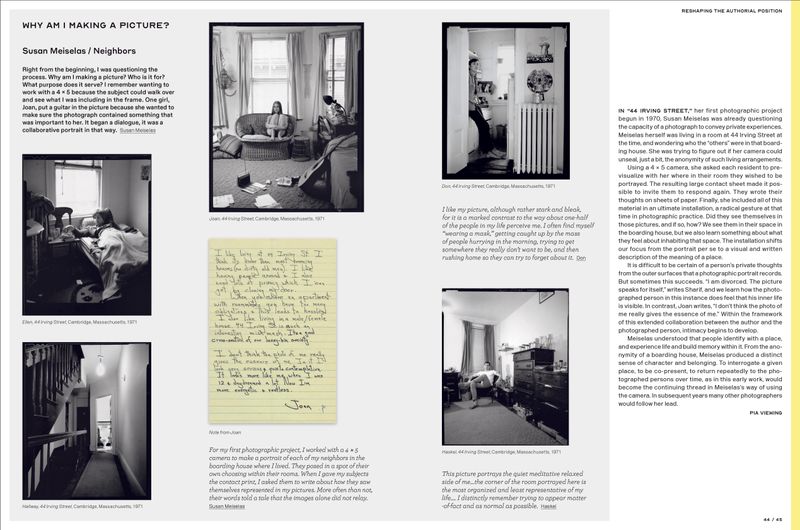

The result is a multi-layered book where five different voices - those of Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, and Laura Wexler - exist layered on top of each other. Divided into ‘clusters’ with titles like ‘The photographed person was always there’, ‘Reshaping the Authorial Position,’ and ‘Iconization is preceded by collaboration,’ it’s a book that is directed to the reader with some prior knowledge of photographic history and practice.

Anthony Luvera (who is not featured in this book) described his collaborative process as one where, ‘Ultimately, I am interested in how involving participants as contributors to the processes of representation can inscribe a different, more nuanced view, or otherwise complicate commonly held perceptions of their lives.’ There is a lovely transparency to that idea, a clarity and accessibility that is at the heart of so many collaborative projects.

An example of this transparency, and the idea of adding nuance and humanity is evident in Photo Requests from Solitary, a beautiful project where prisoners in solitary (subject to human and sensory deprivation) make requests for images from the outside world. It’s a project where the process is to the fore, a process that is evident in the provision of some form of human and visual contact to the prisoners, but also one where the story of that process served as part of a broader campaign to end such a brutal form of incarceration.

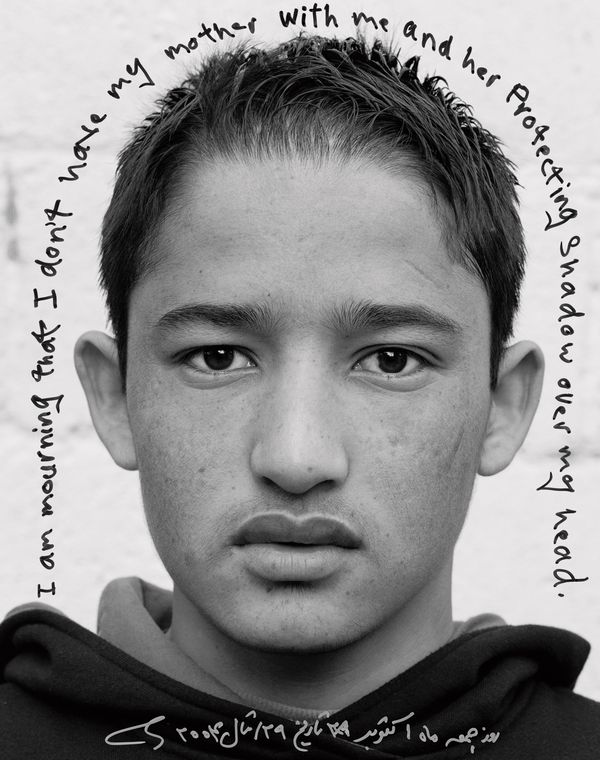

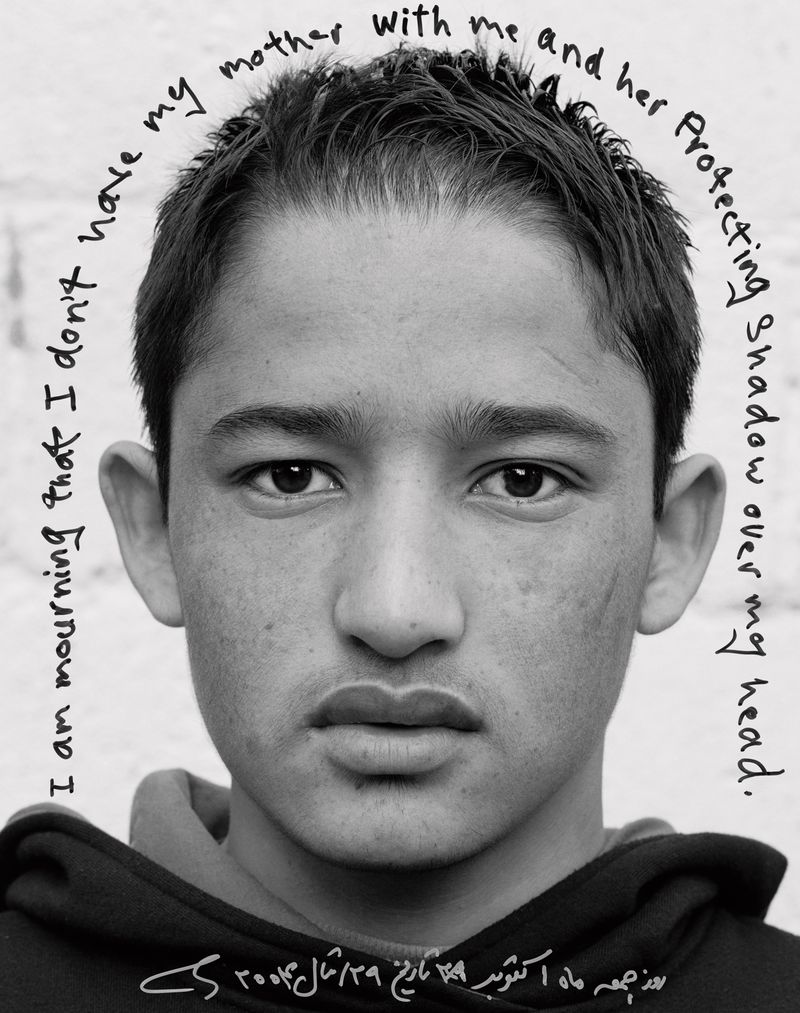

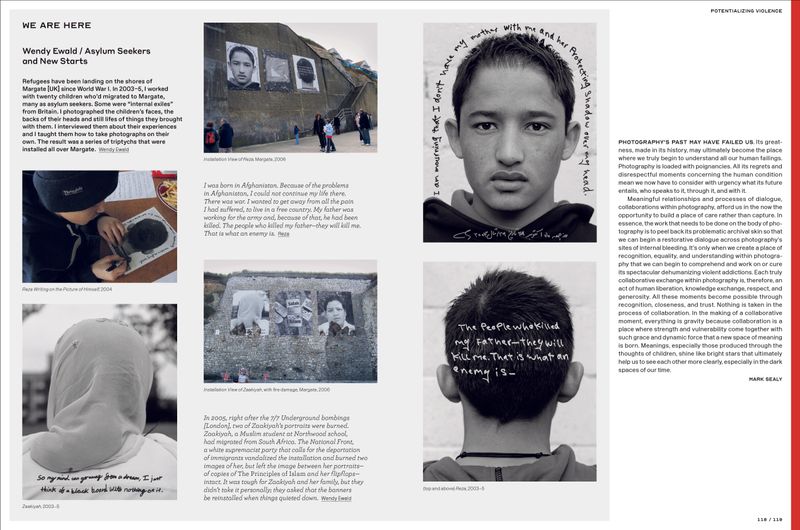

More well-known works involving participation with the people photographed come from Bieke Depoorter, Wendy Ewald (one of the authors), Jim Goldberg, and Carolyn Drake.

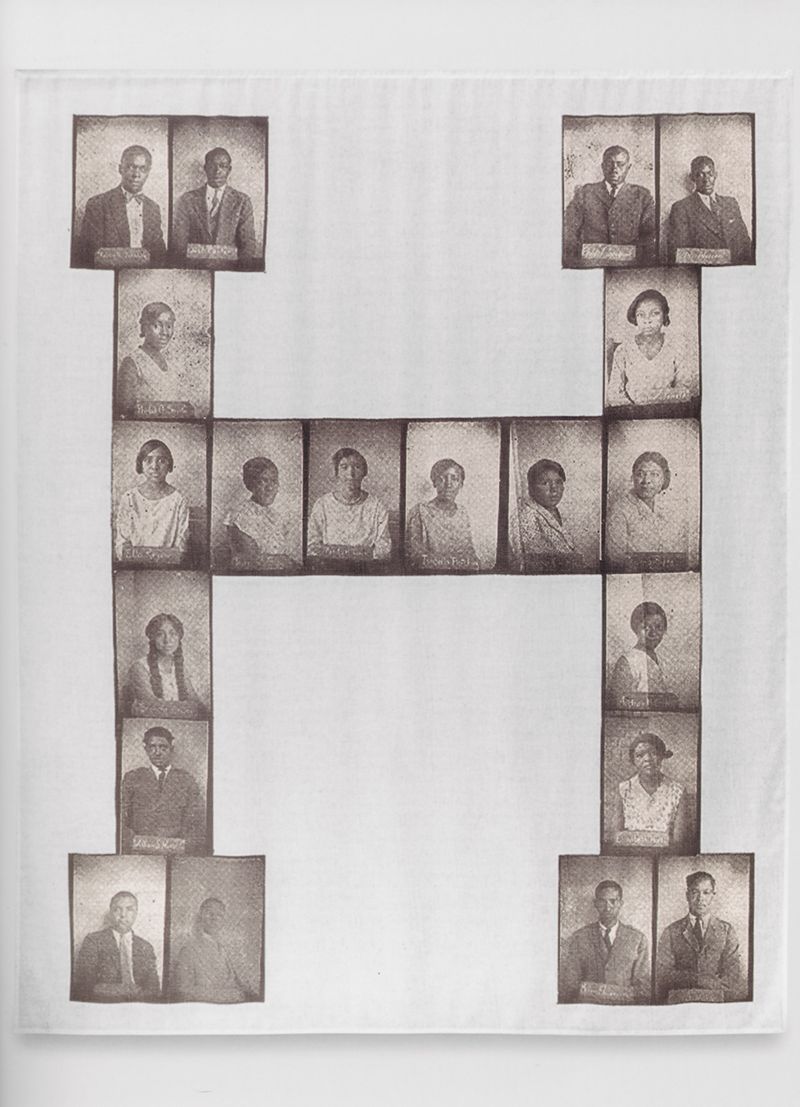

Transforming the archive is at the heart of the Feminist Memory Project in Nepal. ‘The feminist movement of Nepal has a deep history but there has been no sustained effort to document the progress and the struggles of the movement…,’ writes co-founder NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati. The digitisation of photographs is part of making this progress and struggle visible. ‘To become public is to be seen and accounted for in history,’ she says. It’s a very simple idea, one that everybody can understand; if you change the archive you change the representation.

A related idea is apparent in Femen's use of the politicised female body 'to break out of the prison' (of the male gaze). For Femen, the body internalises injustice, is frozen by injustice. To regain the joy of the body, to rediscover its freedom, '...you turn your body against this injustice, mobilizing every body's cell to struggle against the patriarchy and humiliation. You tell the world: Our God is a Woman! Our Mission is Protest! Our Weapon(s) are bare breasts!'

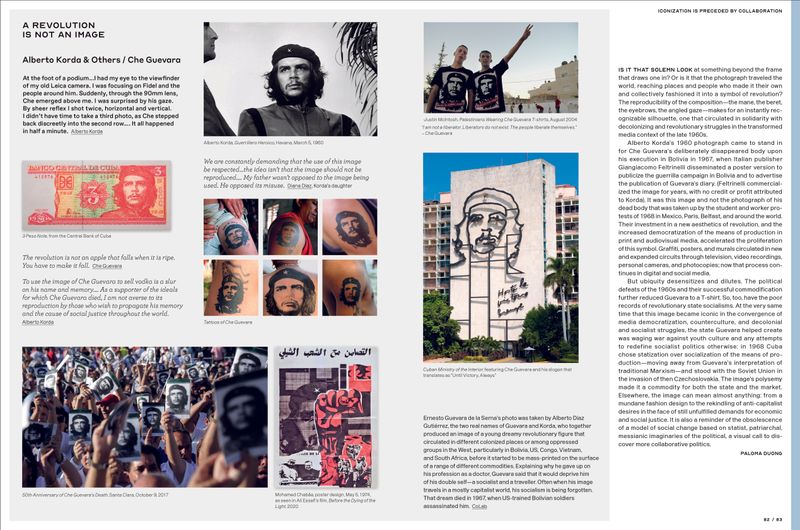

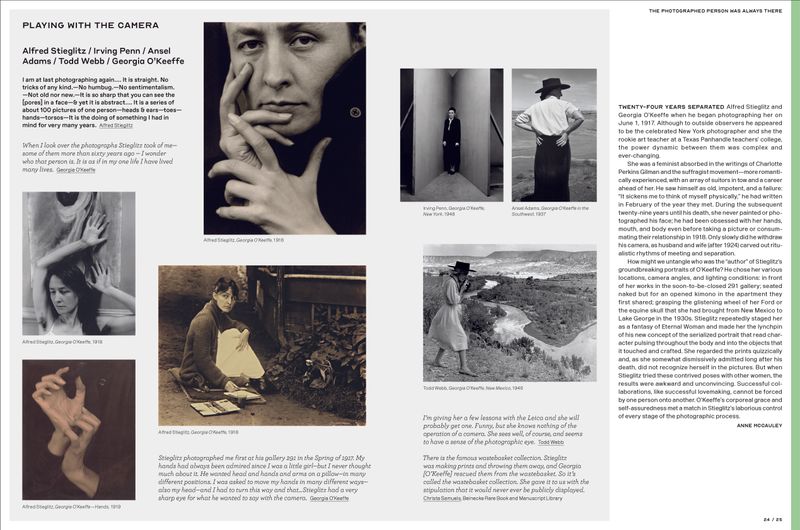

The way images change in time are evident in iconic photographs such as Nick Ut’s picture of Phan Thị Kim Phúc screaming as her skin burns from napalm, or Steve McCurry’s portraits of Sharbat Gula, the fates of the people photographed changing something (though this, like much in the book, is up for debate) of the rhetoric of the image.

At the start of the book, there is a series of (Notes) towards a manifesto that explains the importance of applying ‘the lens of collaboration to see how people who involved willingly or not in… violent photographic situations.’

Some examples of these violent photographic situations are Marc Garanger’s identity pictures from Algeria (under the title, Forced to Collaborate), Li Zhensheng’s pictures from the Cultural Revolution, and the identity pictures from the Tuol Sleng archive (an archive that formed a central part of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum) in Cambodia. This archive is one where (with the exception of the handful of prisoners who survived when the prison was liberated), the identity photograph was an initial step before torture and an inevitable and terrible death. Here photography is described as collaborating in the ‘bureaucracy of death.’ It’s something the prison’s main photographer, Nhem En participated in fully. In this 2008 interview he said, “They knew they’d die… The work was necessary,” he says. “We needed to know who our enemies were.” The world should thank me for my work. If I hadn’t taken those photos, if it weren’t for me, no one would know or care about Cambodia.”

Sited in the Sovereign and civil power of the apparatus cluster, It’s an example of how the book stretches ideas of collaboration into those ethical areas that are beyond the pale, as a counter-example of how photography serves as a tool in larger, more significant histories.

Martha Rosler famously wrote that ‘Documentary, as we know it, carries information about a group of powerless people to another group addressed as socially powerful,’ and even in the most collaborative of projects, there is the question of how class, caste, education, wealth, gender, religion, nationality, political power, and many more factors play out in collaborative projects.

Does collaboration always add nuance to a project or can it be used as a kind of participation-washing that will blind the viewer to the otherwise all too apparent power imbalances between the photographer and the people or communities photographed?

This book raises questions about who a photographer is, where they come from, who they work for, and what it means for them to photograph in a particular place at a particular time. Not all the questions are answered, possibly because they are questions that are too numerous and complex to answer in the confines of a book that, in the messiness of its multi-authored construction, will take multiple readings to even begin to try to answer. It might be that there are no answers. Only questions.

--------------

Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography

By Ariella Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, Laura Wexler

Published by Thames & Hudson: 2 November 2023

£60.00 hardback

--------------

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His latest online courses begin in January 2024. Follow him on Instagram