Reviving the Stories of Peru’s Forcibly Sterilised Peasant Women

-

Published29 Jul 2020

-

Author

Peruvian photographer Liz Tasa revisits the stories of Indigenous peasant women who were forcibly sterilised during Alberto Fujimori’s dictatorship twenty years ago. Tasa sets out to investigate the aftermath of these violent events that continue to torment many women and their communities today.

Peruvian photographer Liz Tasa revisits the stories of Indigenous peasant women who were forcibly sterilised during Alberto Fujimori’s dictatorship twenty years ago. Tasa sets out to investigate the aftermath of these violent events that continue to torment many women and their communities today.

During Alberto Fujimori’s presidency in Peru - between 1990 and 2000 - the National Program of Reproductive Health and Family Planning was executed. The main goal of this program was to reduce poverty and it aimed to reduce fertility among rural indigenous women with high levels of poverty who were mostly peasants. According to Peru’s ombudsman's office, 272,028 women were sterilised through this program says Liz Tasa.

The systematised program had doctors comply with sterilisation fees and make direct reports to the president at the time. Given the urgency of reaching the nation’s goals, a high level of negligence was committed. Due to malpractice, many women have died since, and others have developed cancer of the uterus or strong infections in their wounds that have prevented them from working the land as they did before. Photographer Liz Tasa brings light to their stories and looks to pay homage to those who are no longer here to tell their version of events.

Liz, to start with, could you tell us more about the meaning of the title of your project, Kápar? How did you come to choose it for your project?

Kápar is a word that comes originally from Quechua – a South American language spoken in parts of Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador - which means animal castration. For me this was the right word to refer to the violent way in which these women were sterilised. During the project’s process, I had the opportunity to meet and portray the scars of almost all the women I interviewed. There were around 40 women and I could see the violence and brutality that was exerted on their bodies.

Another reason was that many women were disparagingly called Caponas, which refers to the word castrate, within their community. In the Andean areas, fertility is important, that's why not being fertile is embarrassing.

I remember a very strong phrase that the leader of the Ayacucho community, Dionisia Calderón, told me about how her companions made fun of her: “You are a Capona, you are like a mule, why do you think your husband has left you? You were castrated like a pig, like an animal". Doctors have also referred to these women as animals, they told them that if they would get sterilised they would stop reproducing like rabbits. In general, in all my research, I came across these kinds of phrases that reinforced the idea of the title.

In general, my initial projects have been related to issues of social and political racism, I feel that it is a line that I have been working on unconsciously throughout my career. And the issue of forced sterilisations is not only a clear example of racism, but it was also a eugenic, classist and machista practice. It seemed that for the state, being a woman and an indigenous person was synonymous with being a third-class citizen with whom they could violate their rights. For this reason, portraying the subject was important to me; it was to open the wound again and say that as a society we have not lost our memory and that we can still denounce. Since the case still goes unpunished, I was interested in generating spaces for discussion on the subject in the hope that in that attempt something could change, either in the history of these women or in those who encounter the subject for the first time.

Why do you think it is important to raise this issue now?

It is important to bring the issue up to date because many people, mainly the new generations, still ignore this fact and its consequences in the lives of these women 20 years later. Beyond the physical wounds that bad operations generated and that have left these women sick with cancer or infections, there are also emotional wounds.

The fact of being sterile in a community where fertility is so important not only generated rejection in their community, it has also fragmented their homes, becoming abandoned by their husbands for considering it an excuse to be unfaithful to them.

Another stigma is the negative pressure that their community have laid on them making them feel useless for not being able to work more on the land and others have had the need to sell their properties in order to pay for medical expenses, making them even financially poorer. That’s why its importance of returning to the subject and denouncing it to give voice to their stories. It is urgent that the state provide them with an economic and psychological reparation.

Do you think your peers judge as well these women who were "castrated"? Or do you find more sympathy among women regardless of age or background?

I definitely feel that it is a topic that has much more interest among women. During the last years, it has been the different feminist groups in Peru who have continuously demanded justice for the rights of the ladies, especially Somos 2074 group. In fact, my investigation was much easier due to the previous work of other colleagues such as Alejandra Ballón, who has spent years researching the subject, creating in the process the PNSRPF file that is the largest file on the case of forced sterilisations in Peru. They have been in this fight for years.

Is your intention to continue investigating this topic in other countries where women have equally been abused or do you want to keep your attention in your homeland?

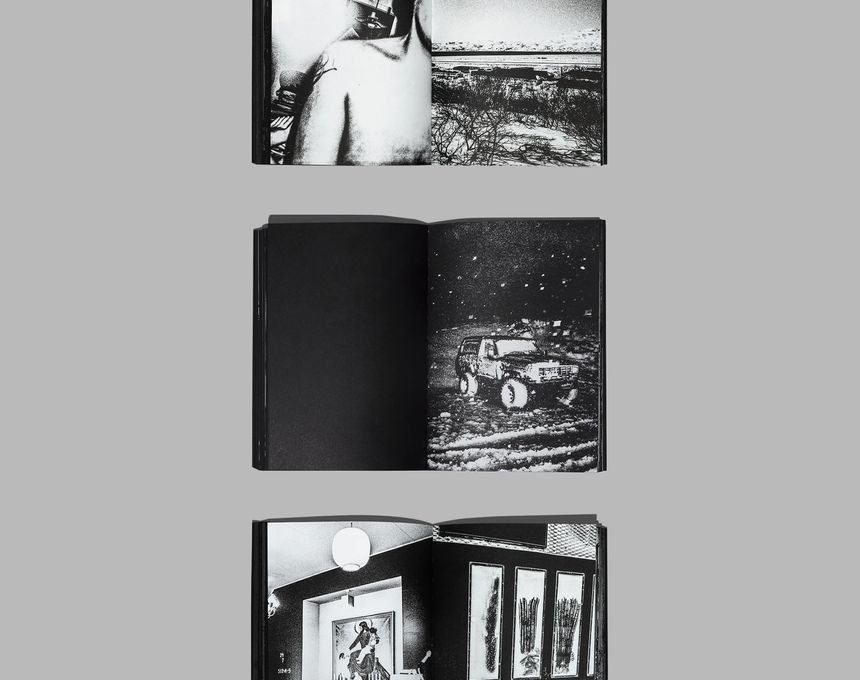

The Kápar project is not yet finished. So far my research has only been based in the southern highlands of Peru, such as; Cusco and Ayacucho, but I would like to continue it in the jungle and in the highlands of Piura, which were important places for the sterilisation campaigns. In the future, I would like the project to be a photobook because I consider it important to leave a visual document on this topic.

Yet, I am interested in working on the subject in other countries, mainly with Mexico, because the same pattern of sterilising indigenous women, and women from rural areas, continues to be repeated. According to what I have read, it is a practice that has been denounced since 2001 to the present. My wish is to be able to look for financing aid to make this connection between both cultures since they have a very similar worldview.

-------------

Liz Tasa is a Peruvian documentary who focuses on topics around social exclusion, racism and human rights. She has been shortlisted for prestigious contests like; PHOTO IILA and POY Latam 2019. She has participated at numerous group exhibitions in Peru and overseas. Follow her on Instagram.

Verónica Sanchis Bencomo is a Venezuelan photographer and curator based in Hong Kong. In 2014, she founded Foto Féminas, a platform that promotes the works of female Latin American and Caribbean photographers. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

-------------

This article is part of In Focus: Latin American Female Photographers, a monthly series curated by Verónica Sanchis Bencomo focusing on the works of female visual storytellers working and living in Latin America.