Passion Play: A small history of anti-semitism in pictures

-

Published27 Apr 2023

-

Author

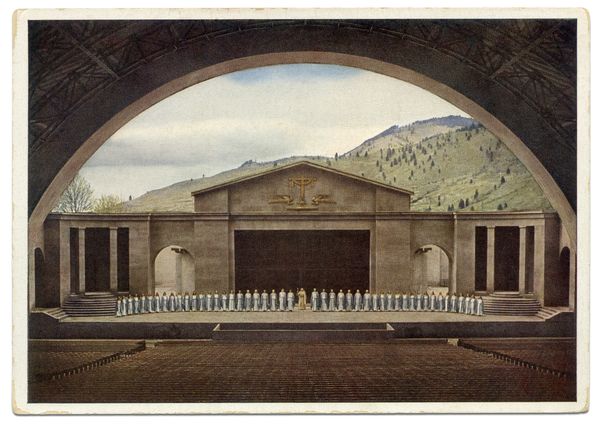

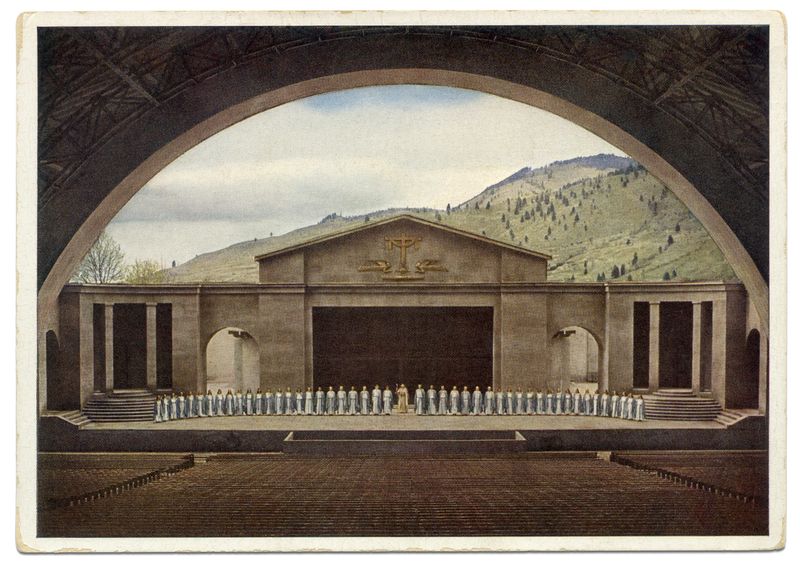

Passion Play by Regine Petersen is an exploration of the story of the last days of Christ as performed in a Bavarian village. It’s a story where Nazism, persecution, and the underlying white supremacist representations of Jesus, Judas and Mary loom large.

It was Kaspar Schisler who brought the plague to the isolated Bavarian village of Oberammergau. Sneaking past the guards who sought to quarantine the hamlet from the ravages of the disease, he returned home to visit family he missed while working in a neighbouring district. Schisler died soon after reaching his family in Oberammergau. In the years that followed, so did half of the village.

Laid low by plague in a region reeling from the horrors of the 30-year-war (as featured in Daniel Kehlmann’s enjoyable novel, Tyll), the villagers pledged to God that if only he would relieve them of their sufferings from the plague, every 10 years they would turn out in their entirety to perform the trials, tribulations, tortures, and death of Jesus Christ.

And so the Passion Play of Oberammergau was born.

Petersen’s book is a recounting of the 20th century history of the play through travelogues, through local news bulletins, through denazification trials, and through postcards. It’s a recounting in which representation is made to be seen to matter, in which the theatrical representations have an effect on real life, where the line between history, fiction, and politics all overlap.

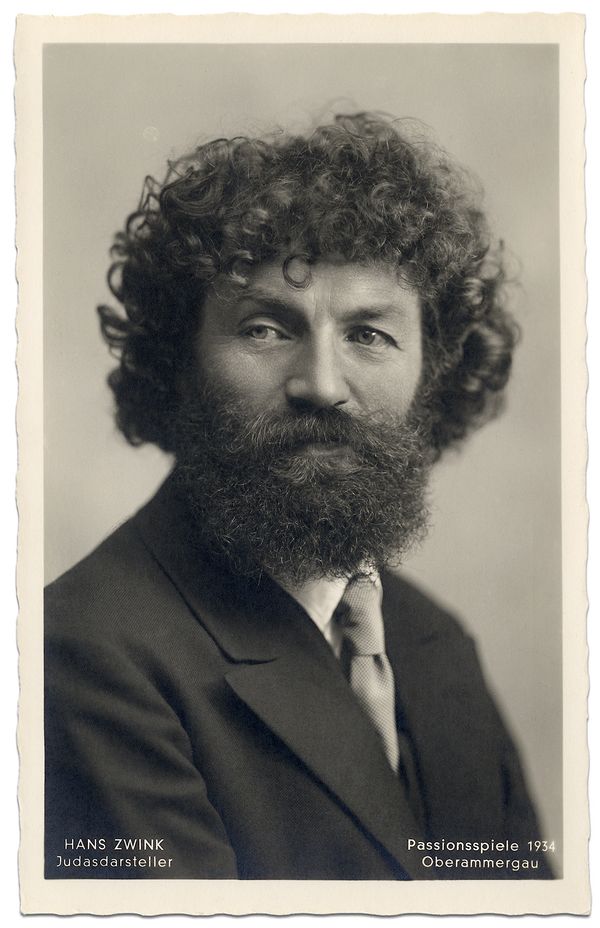

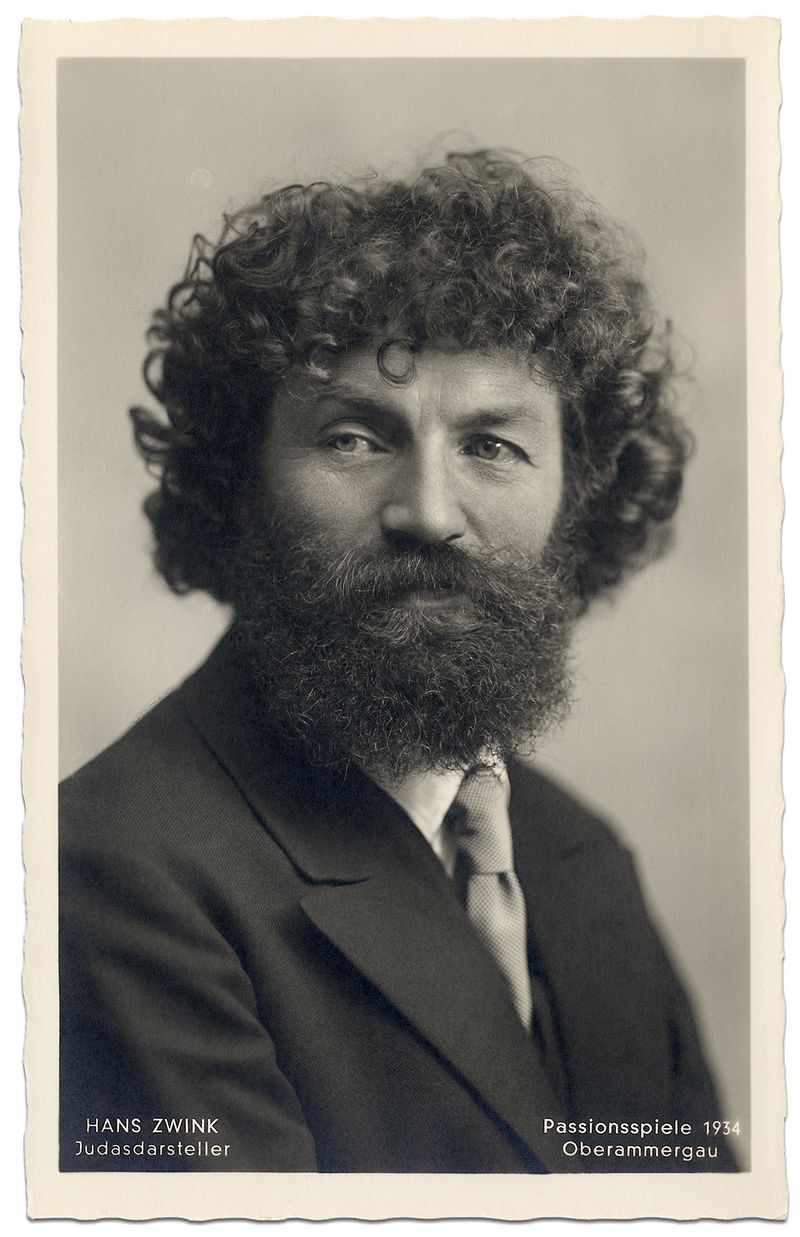

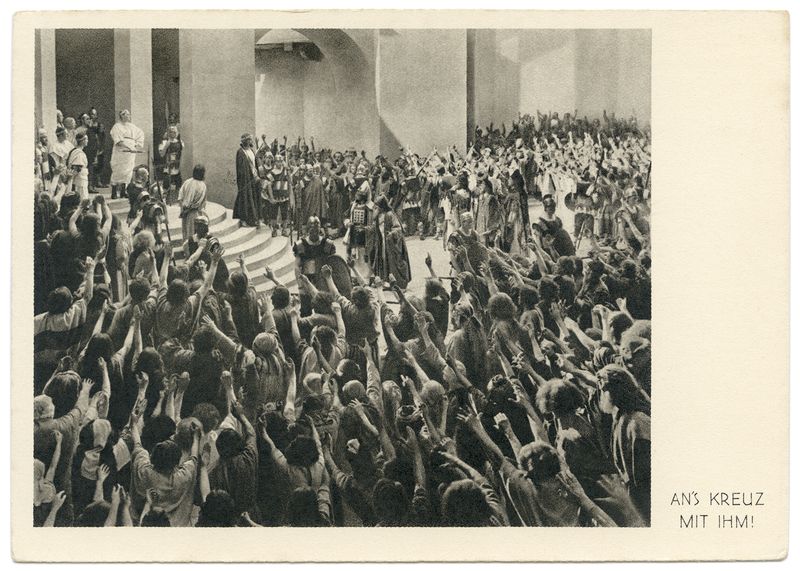

So we see postcards of the performers playing Judas and Caiphas (the Jewish high priest who oversaw the trial of Jesus), symbols in Nazi Germany of Jewish involvement in the murder of Jesus, a reading that always skips over the Jewishness of Jesus himself.

The casting of Judas and Caiphas goes along Nazi physiognomic principles, with the same being true for those actors playing Jesus and both Marys, fresh-faced, straight-haired, white-skinned, and straight-nosed. It’s casting straight out of the Hans Gunther (Hitler’s favourite photography ‘theorist’ and visual eugenicist) playbook.

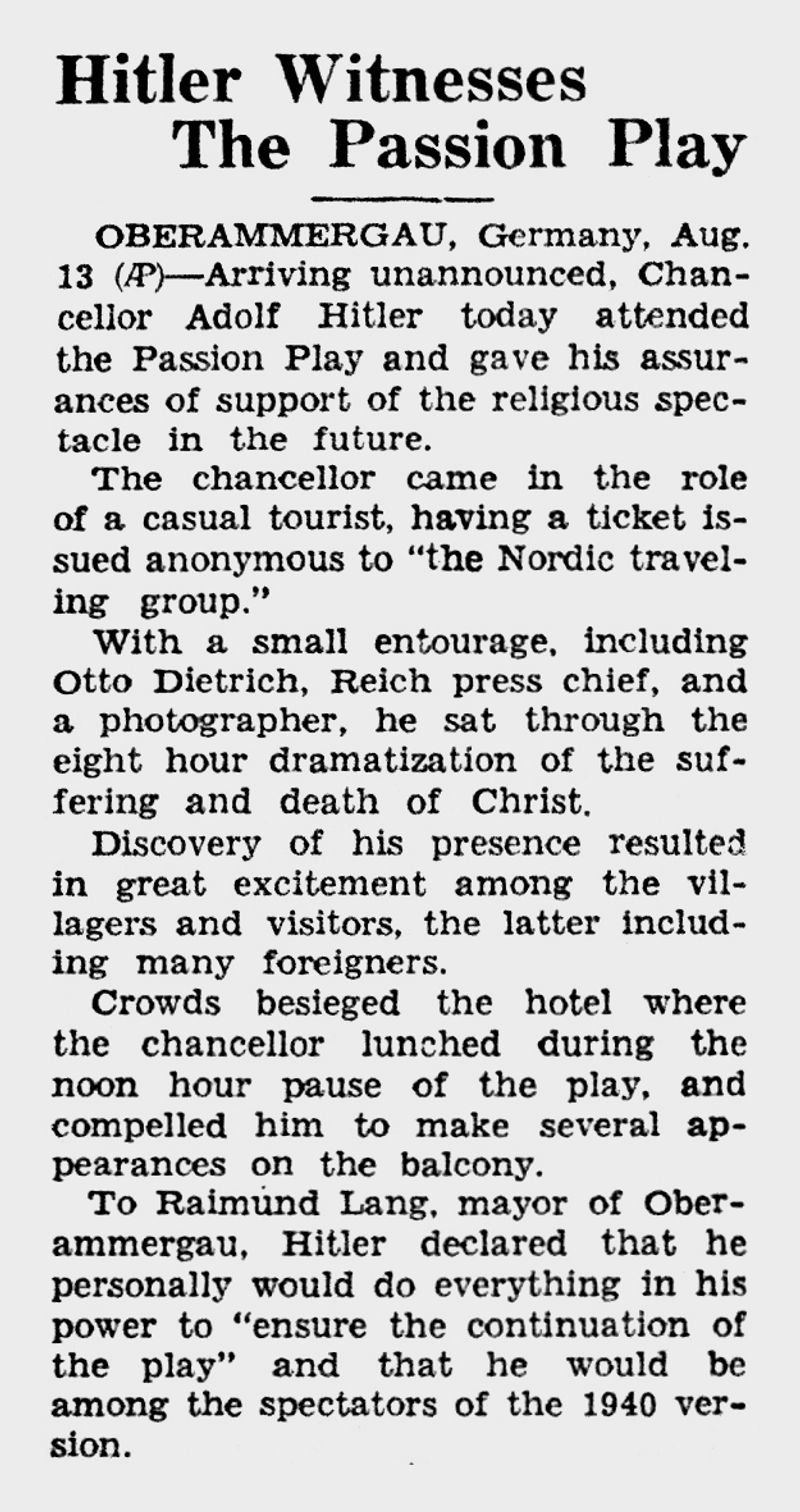

Hitler attended the Passion Play in 1934, and as the decade progresses so the banal violence of Nazism seeping into every corner of village life begin to dominate. We see this in police reports of events in the village in the 1930s. We hear about the lack of incident, how the cultural policy of press coverage is consistently ‘keeping within the framework of the National Socialist framework. Writing and books with subversive content are not being distributed.’

Most of all we hear about Max-Peter Meyer, the ‘Jewish resident… who was baptised in April 1935 and subsequently joined the Catholic church.’

We hear about his participation in village life, his increasing isolation as the decade progresses and then learn (in an extended essay at the back of the book) of his persecution during Kristallnacht, his imprisonment in Dachau and his escape to Britain. While in Britain, he is exiled to Australia on a ship with relatives of Sigmund Freud and Walter Benjamin as fellow passengers. He returns to Germany in 1949 and dies in 1950.

In the postwar years, there are texts dealing with denazification. Alois Lang, a Nazi party member is replaced in the 1950 revival of the play by Anton Preisinger, another former Nazi party member. Hans Zwink, the performer who played Judas in the 1930s, was not a member of the Nazi Party, and does not get a part in the 1950 revival.

The post-war years are years of denial, of an asymmetric amnesia where people ‘no longer hate each other’. It’s a world in which Preisinger, the director of the play in 1970, says ‘people should stop talking about these things.’

Today, non-Christian residents of Oberammergau have been allowed to perform in the Passion Play, there have been alterations to the lines, Jesus is referred to as Rabbi Yeshuah, and some of his lines are spoken in Hebrew. Things have changed in other words.

Petersen’s Passion Play helps us question how religious figures are represented in art, in theatre, and the political ramifications this may have in real life. The Oberammergau performances are a small manifestation of how we see and think of historical figures, how white supremacism inserts itself into almost every visual facet of our Christian institutions and, if we are that way inclined, our spiritual lives. Then. And now.

Passion Play – published by the Eriskay Connection

Regine Petersen

155 × 220 mm | 176 p

EN | hardcover

First edition: 750

ISBN: 978-94-92051-81-3

€ 35.00

Regine Petersen is an artist and researcher with photography at the core of her practice. Her work starts with specific and often coincidental findings, which she uses as departure points to gain insight into more universal notions of memory, history, storytelling and ideology.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His latest book, Sofa Portraits is available here. Follow him on Instagram.