On the Pleasure of Words, and Curatorial Irreverence: an Interview With Federica Chiocchetti

-

Published27 Jul 2023

-

Author

Started out with the exhibition "Le Plaisir du Texte", Federica Chiocchetti’s journey as the museum director of MBAL, Switzerland is one of contamination, generosity, and productive obsessions.

The online and offline platform Photocaptionist derived its name from a dream. A grumpy man, whose job title was indeed photocaptionist, daily produced texts accompanying photographs he received from institutions. The dreamer is Federica Chiocchetti, who for several years combined her independent curatorial practice, her editorial work as Photocaptionist, and a PhD at the University of Westminister, where she was delving into the photo-text relationship through history. Since 2022 Chiocchetti is the director of the Swiss beaux-arts museum MBAL: Le Plaisir du Texte, her first exhibition in this role, is an exploration of the pleasure of reading - one where words become images, and images become words.

Looking at your work as Photocaptionist and at your PhD research, the theme you’ve chosen for your first exhibition at MBAL feels very personal, and connected to questions that have been with you from very early on. What is originally attracting you to the analysis of photo-text relationships so closely?

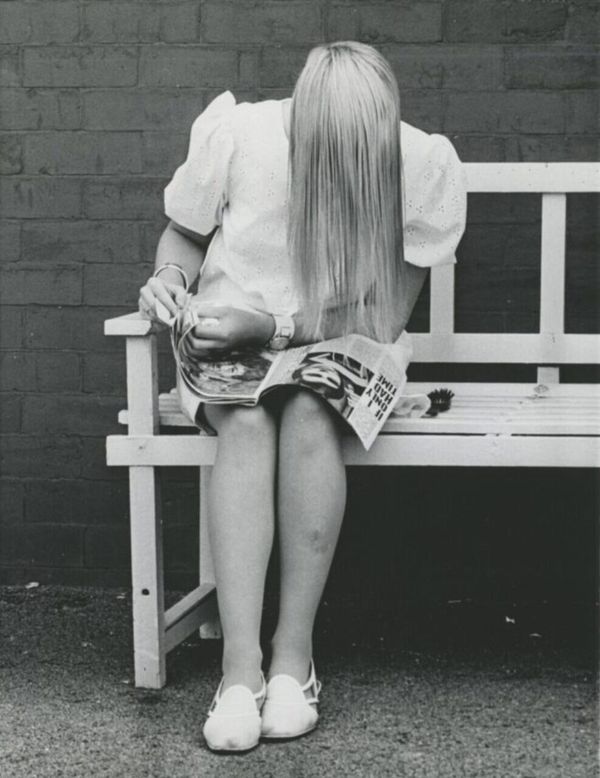

When you’re obsessed with something, you’ll unavoidably see it everywhere. Even when you’re not looking for it, the thing will periodically find you. I had just started working at the museum, drowned in complex information - going from working as an independent curator to being a museum director, with all the administrative and bureaucratic complications this carries, plus a one year old baby Orso, was a huge leap. I went hiding in the room of the permanent collection, looking for some peace. Going through the archival nets, I started noticing paintings that showed people, especially women, reading. This made me think of the book Les femmes qui lisent sont dangereuses by Laure Adler and Stefan Bollmann, a sort of art history through the lens of the female reader. A light bulb went on: maybe my PhD photo-text research could come back, and be re-translated into a multidisciplinary exhibition where all arts and all eras would meet, and intertwine. The Pleasure of Text, a very short book by Roland Barthes, was a main inspiration. From there on, I started building a two-axes path. One aimed to explore the diverse ways in which text can give us pleasure: as readers, as writers, as concrete poets, as graphic designers, conceptual artists, photographers. The other shaped a trajectory originating from an imaginary text: we cannot know what someone painted on a canvas is reading. Just as mysterious are the 467 books, sculpted in wood, that compose Swiss artists Lutz & Guggisberg’s imaginary library. From this virtual text that you cannot see, we then transition to a slow and gradual invasion of the image, where words become the artworks’ main characters, as in the case of Nora Turato or Italian photographer Luca Massaro.

When text is placed next to a photograph, it usually tends to define, to anchor, the otherwise fleeting meaning of the image. Looking at the works that you decided to exhibit, it seems like you went after an opposite kind of relationship: one where the ambiguity of images is invading, and fortifying, the ambiguity of text.

Absolutely. I did not choose Barthes as a source of inspiration randomly: he’s the only one who ever actually theorized text-image relationships through the notions of anchorage and relay. Anchorage, as you mentioned, takes place when a piece of text stabilizes the meaning of an image. On the contrary, relay doesn’t reduce meaning: it catapults it elsewhere. To a place that does not originally belong to the image. It impresses in the retina elements that wouldn’t be there otherwise. Unconsciously, but not even that much, I’ve certainly been attracted by works of this kind - showing a relay, more than an anchorage, mechanism.

Are there sides to this theme that you had not considered or crossed yet, and that instead you could explore through Le Plaisir du Texte?

It’s two historical extremes. On the one hand, it was the first time that I included old paintings in an exhibition. On the other, I had never addressed artificial intelligence. If you think of AI-generated images, they intrinsically are photo-texts: the image generates as you write it. With AI images becoming more and more of a trend, already too fashionable, I grew more interested in algorithmic text. South African artist Nelis Franken made for the exhibition a leporello called Perfect Forest, where the typical AI text-image relationship is reversed: here, the images are his own photographs, and the text - which is, creepingly enough, very poetic - was algorithmically generated starting from keywords. The leporello shape was really fitting to me, as the visitor can touch it, manipulate it, open it and close it, and read it all.

There are several books you exhibited as objects.

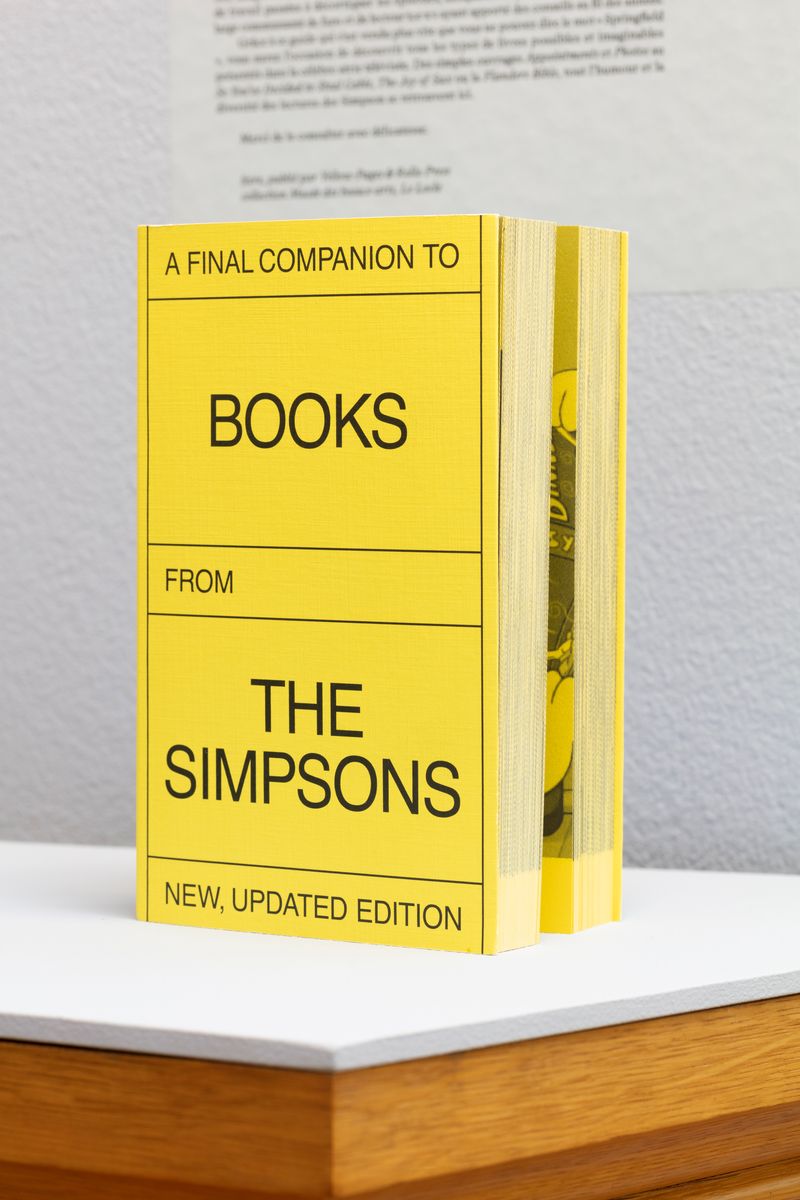

A book is a work of art. They have the wonderful characteristic of making a space more familiar and pacing the exhibition’s navigation as they slow down the visitors who consult them. More in general, I like to soften atmospheres and create contrasts between pop and rigor. I wanted, for example, to break the seriousness of the reading women’s paintings: this is why I exhibited Olivier Lebrun’s publication A final companion to books from the Simpson in their same room. Published by Rollo Press, the book collects screenshots of moments in the tv series where characters are reading a book - at times they’re existing volumes, at times they’re totally made up by the director.

Starting from how you approached this exhibition, but also looking at your work more broadly, how do you see your curatorial practice?

I see it as very eclectic, eccentric, and certainly a little bit irreverent, too. Swiss curator Harald Szeemann was for me a legend, and I often look at his work as a guiding reference. He was the first independent curator in history, making unsettling exhibitions that almost introduced new artistic movements. His Duchamp-like operations mixed non-artistic objects with works of art. In Le Plaisir du Text, I included artifacts that I saw as intruders, triggering tensions and hopefully amusing reflections. It was my humble hommage to him. I think curating is telling a story through objects, which are at times works of art, at times not. Humor, contrast, and an eye on the visitor’s rhythm are always needed: to break a flow, to astonish, to contradict, so that people can have fun, laugh, cry, get mad…

Before, you mentioned the struggles of adapting to your new role.

It was more intense than I expected. Naively, I thought I would deal mainly with exhibitions. Instead I’m searching for funding, managing a great team, taking care of the political and administrative issues that take a lot of energy. Thankfully in my previous life I also studied economics which really helps today, but I’d say this was the year when I learned the most in my life. Also, as a very direct Italian from Tuscany, I am learning Swiss diplomacy, which is very intriguing. Nevertheless, I want to be faithful to who I am: a transparent person who respects hierarchies, but prefers a horizontal way of management. I treasure everybody’s opinion, even though I know that the final decision is up to me; it is important to establish a friendly and collaborative environment where people care about one another, and where they aim to shape a beautiful project together.

Can you disclose something about what will be next at MBAL?

The next exhibition’s formula replicates the current one: the permanent collection works as a trigger for a theme to emerge. In this case, it will be animal instinct. There are many animal studies artworks in the collection, indigenous works of art from Canadian Inuit artists, bears that are made out of whales’ bones… it’s a beastly cabinet of curiosities. I invited contemporary artists working with photography, such as Marta Bogdanska with Shifters and Vive La Résistence, a project where she studies all the forms of resistance that characterize man-animal relationships. Video artist Patrick Goddard will show his brilliant dystopian video pieces Animal Antics and Lonely Planet, Italian Emilio Vavarella will bring his award-winning video Animal Cinema, an incredible work of art that uses found footage of animals who by chance encountered, or stole, cameras, activating them with unconscious movements.

Is this a method you’re developing, always keeping the museum's permanent collection as a starting point?

Yes at the moment I am really enjoying this method. I start from the collection, find a theme, and invite Swiss and international contemporary artists. Sometimes, as in the case of Marta Bodganska’s work, the two dimensions come together: she will include the permanent collection’s artworks in her installation, choosing paintings that are in line with her iconographic research. She will create clusters and clouds shaping new links, new relationships, between her practice and the heritage of the museum.

--------------

Le Plaisir du Texte is open in Le Locle, Switzerland, at MBAL until 18/09/2023.

--------------

Federica Chiocchetti (b.1983) is a writer, curator, editor and lecturer specialising in photography and literature. Appointed director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Le Locle (MBAL) in June 2022. Founding director of the platform Photocaptionist, collaborating since 2014 with international institutions such as Jeu de Paume, Foam and Fotomuseum Winterthur. PhD in Photo-Texts (University of Westminster, 2020), she was Art Fund Curatorial Fellow of Photographs at the V&A and Nottingham Castle Muesum. Her book 'Amore e Piombo' with The Archive of Modern Conflict won the 2015 Kraszna Krausz Best Photography Book Award.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based between Italy and The Netherlands, graduated from MA Information Design at Design Academy Eindhoven (NL). Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.