Of Affection Within Critique: Interview With Nadine Wietlisbach

-

Published20 Feb 2024

-

Author

A Show of Affection - Collection Constellation 1 is the first of a series of exhibitions inquiring into Fotomuseum Winterthur’s collection. Its director reflects on what it means to collect photography, and to try to preserve its meaning through time.

A museum is a fascinating, complex structure. Like an iceberg, it only shows a tiny percentage of itself. Crucial activities happen far from vitrines, frames, and curatorial paths. Entire teams of people relentlessly work to accumulate knowledge, embedded in material forms - a stone, a painting, a letter, a photograph. They need to preserve it, both physically and conceptually: shapes must not deteriorate and meanings must keep speaking, even when the context around them changes constantly. It is a fight, or a dance, with time. On its 30th anniversary and in the midst of a huge renovation, Swiss institution Fotomuseum Winterthur looks inward: what have they collected until now, and how? What have they not, and why? As A Show of Affection - Collection Constellation 1 was building up in the background, we met with museum director Nadine Wietlisbach to delve into her critical practice - and into all the love and care it needs.

Why did you decide to engage in a self-examination of the museum’s collection?

The museum has been existing for more than 30 years now. The collection starts from the 1960s to then go into the radical nowadays. It is organised through thematic focuses: there is documentary narrative photography, and post-documentary journalistic photography. There is conceptual photography, there is post-photography, there are acquisitions from young photographers. Then, there is a rather large ephemeral collection of works that aren’t necessarily artworks in a classical sense. We wanted to speak about these different typologies of photographic practices, while looking at specific work that carries a very particular meaning for the museum. It is the case of The Sky on the Eve of Philippine’s Death, Winterthur, Switzerland by Nan Goldin. Her exhibition here in 1997 was one of the very first ones in Europe. We tried to intertwine theoretical narratives, changes in photography, the background story of our institution, and the artistic voices we have in the collection.

Which works on show do you feel are particularly relevant to the aim of A Show of Affection?

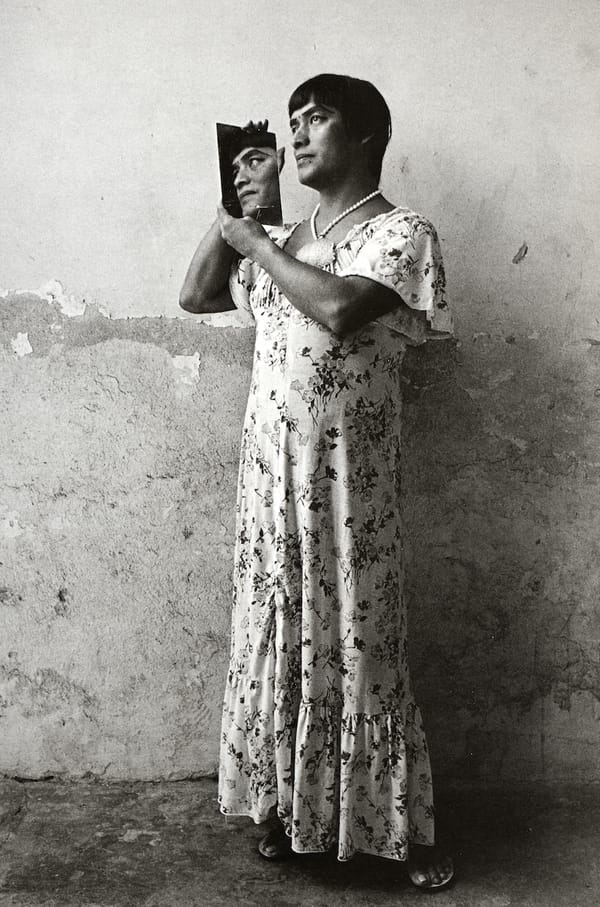

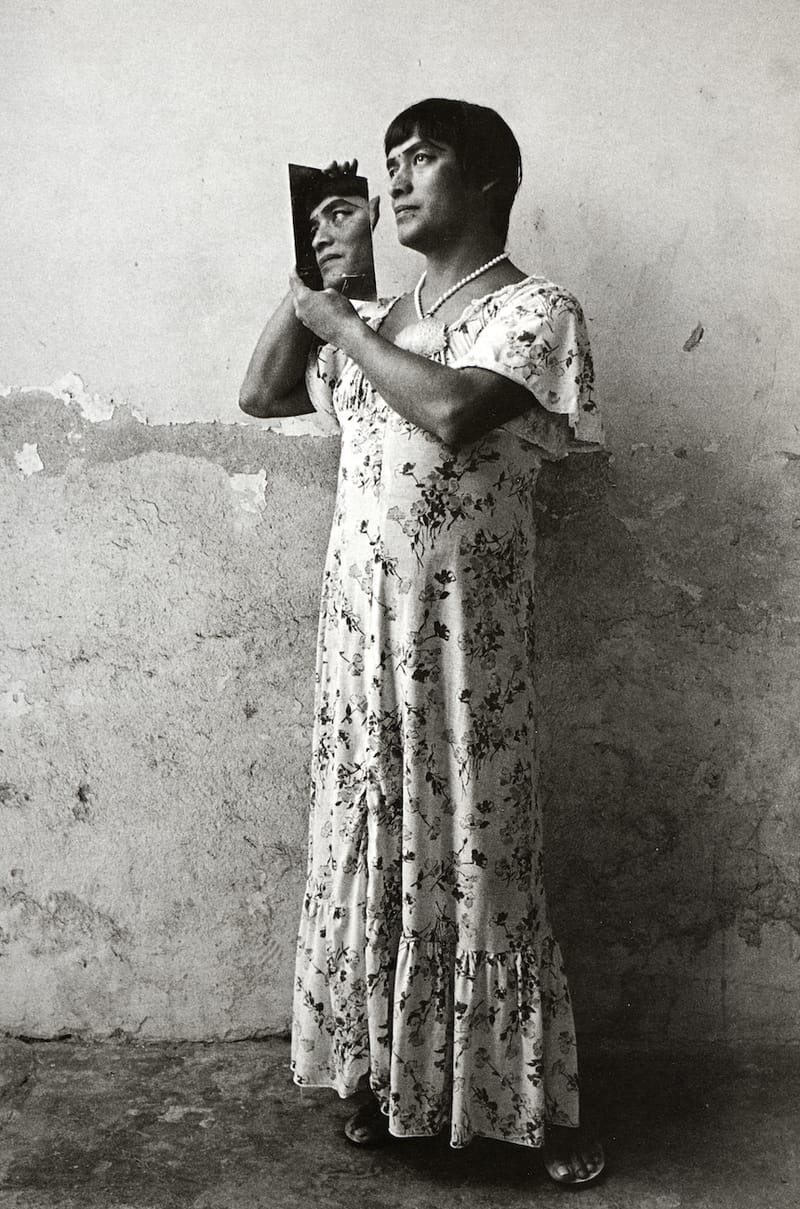

We got interested in looking at what we haven’t collected as much. Questioning our own gaps. We are not an exception in having more work by male artists, for example. So I focused on choosing very specific female photographers or collectives. Sherrie Levine’s After series is one of the examples. Or Graciela Iturbide, one of the rare female documentary photographers who was given a solo exhibition at the museum. A work I’m very excited to be showing for the first time is Lorna Simpson’s Summer ’57/Summer ’09, a highly conceptual body of images that speaks a lot of representation and self-representation. It was about showing work, but also speaking of what we aren’t able to show. This opens up a conversation about the fact that although the exhibition is almost 50/50, it does not give the idea of the actual (im)balance within the collection. And this imbalance cannot be changed that quickly - it is also a matter of time.

Speaking of Graciela Iturbide’s work, the exhibition booklet focuses on the way it was acquired. It says the 7 images now in the collection originally belonged to four different series. We read that “the inherent danger of reducing these series to individual images is that the diverse lifestyles of the Indigenous and queer community in Juchitan are only partially represented in the collection”. Then you write that whenever possible, the museum prefers to collect narrative works: “the photographers’ approach and the narratives manifested in their images are often only apparent in a series or sequence”. How is collecting and curating photography different than other mediums?

It’s always about multiplicity rather than singularity. In the way the work is presented, but also more broadly in terms of the narratives that surround image-making. How political the approach is, how ethically engaged it is, if it is a conceptual work, how the artist has been focusing on questions, how the editing process worked… these are multiple, very important aspects. I would say this is one of the main differences in regard to other mediums being collected. I did a lot of painting and drawing shows before focusing on photography, and it is a very different approach. In many, many ways photography needs sequencing.

You mentioned the collection started in the '60s. Developments in photography were rather fast - shifting from document to art, from photography to post-photography etc. Exhibiting photography it’s such a recent endeavor, taking so much from other types of museums - showing paintings or sculptures for example. What have you learned in your experience with curating photography?

Working in photography is incredibly challenging. It plays a role in so many different areas. It’s not an overestimation to say that no other medium is shaping us as a society as much as the photographic image does. So because we are working with photography, we are obviously not only looking at art practices involving it. We are also looking at visual culture, at everyday culture, and that’s what makes it so exciting. It has a meaning to you and me as individuals, but then of course it plays a huge role in the way we perceive the world as a community and a political entity. There is a lot to learn from constant changes, too. As a team in the museum, we need to adapt to those different questions that arise. What I learned is to keep a very open mind. Embedding in our practice the history of photography, the contemporary, and a speculative future, too. Which makes it very rich.

I’m guessing the museum has acquired pieces, such as series of prints, which have a specific, stable form. How is it like to put together different works having different, pre-defined shapes, that maybe don’t necessarily go along?

There is work that has sort of a fixed, stable form, like a print. But we also have work like <YO> <YO> <YO> by Roc Herms, which is changing because of the technical equipment it uses. I think it’s exciting if it’s both - very clear, conclusive, sort of non-negotiable forms and other forms allowing for freedom. Especially as long as the artists are alive and approachable, there is always the chance to have a conversation - how shall we edit, do we edit at all?

Thinking of the relationship between photography and collecting practices, do you think photographic material is somehow “resisting” collecting impulses? Or is it at the same time enabling, fostering them?

I love this question. I think it highlights the ambivalence of collecting a medium which has many different forms, and is in constant flux. This is one of the most exciting things to think about. Despite all the knowledge we have on conservation, at the same time we constantly have to figure out new solutions. How to preserve. And not only the works, right? How to preserve the context, the narrative, the poetics. I think it is something very intriguing. To briefly answer your question: it is both. There is a lot of friction. But at the same time it’s one of the most exciting mediums to collect. I’m very passionate about it.

Let’s imagine we are entering the exhibition space - what does A Show of Affection look like?

There is a very subtle grey wall colour and there is very little text. The artworks, the photographs, the practices are the main narrative. If you like, you can just wander through the exhibition space and sort of soak in all those different visual qualities. There are ephemera, too - and showing them in an exhibition context is always trial and error. They speak a lot of what photography can be. Used, created for, instrumentalized, adding a sort of counter-narrative. We included four media interviews done with different people speaking about the collection. There is Shirana Shabazi telling the story of how her work became part of our collection. There is Thomas Seelig, who was the collection curator from 2003 to 2018. Géraldine Feller, our conservator/art-handler, speaks about preservation; Doris Gassert, our research curator, reflects on finding a balance between research and experimental approaches within the collection. So there is also an auditory level in the exhibition, it creates different entry points also for different audience groups.

How does the institution work in terms of human resources? I’m thinking of conservation, of logistics… going a bit behind the scenes of what collecting means, also very practically.

We work collaboratively as a team, with a very interdisciplinary approach. We have a media scientist, a media artist, a photography historian as part of the curatorial team, I have a strong background in the contemporary arts, and education is also hyper important to us in developing projects. Those are the people working mainly on the content. Then, as you said, it’s very much interlinked with the person who is taking care of the collection, also as a critical care taker, the art handler. Then we have a person working on the loaning process, because we also give out loans to other museums. So there are quite many resources being part of this process. It takes a lot of responsibility to take care of a collection. And we are a mid-sized museum - smaller than a lot of people assume.

Why affection as a title and as a leading concept?

At Fotomuseum we tend to have a very critical approach, not only towards our own collection but towards photographic practices. Also the way we talk about photography in our communication doesn’t go like “oh, you know, this is the most important living photographer”. It’s never about superlatives. We react very nervously on the idea of the “genius-artist”, we are questioning that canon and its consequences. But in order to be critical, you also have to be affectionate. It’s maybe a bit of a bold statement but it’s important to say that our collection is really interesting. We are proud of it. We have admiration for all the artists that are part of it. But that doesn’t mean that we cannot ask a lot of questions. Being critical and being affectionate is an interesting combination to start from.

--------------

A Show of Affection – Collection Constellation 1 is open in the spaces of Fotostiftung Schweiz at Grüzenstrasse 45, Winterthur, until 20/05/2024.

--------------

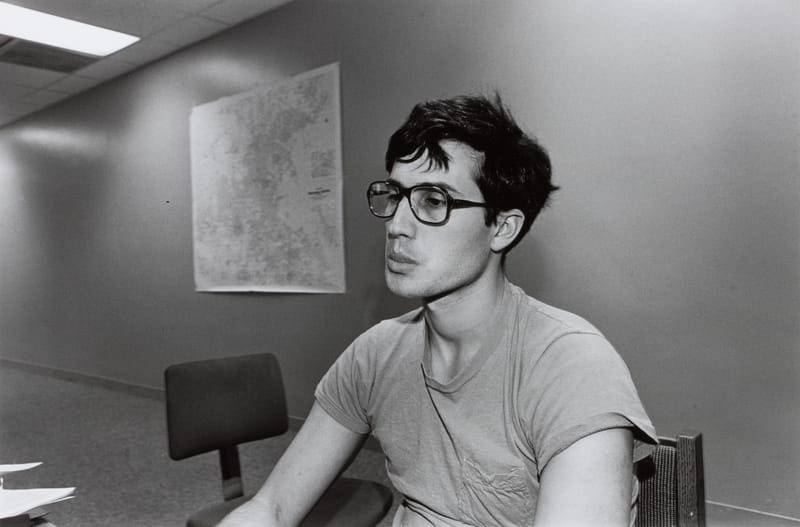

Nadine Wietlisbach devises exhibitions, publications and other discursive formats in the fields of contemporary photography and art. She is Director of Fotomuseum Winterthur since January 2018. From 2015 till 2017 she was the Director of Photoforum Pasquart Biel/Bienne, following her post as a curator at the Nidwaldner Museum in Stans. She founded the independent art space sic! Raum für Kunst in Lucerne in 2007. She worked for various institutions in South Africa and the States, lastly at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based between Italy and The Netherlands, graduated from MA Information Design at Design Academy Eindhoven (NL). Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.