Rediscovering the Magic of Rituals in Southern Italy

-

Published5 May 2022

-

Author

When she realized that the work of southern Italian photographers seldom appeared in photography books on the Italian South, photographer Alessia Rollo launched a research project with two burning questions: Who has represented the South? And which stories have been presented?

“There was a representation of the social cultural life of the South categorized by rationalism and positivism that didn’t match what I remembered and the whole southern cultural and social system,” Rollo says.

The challenging answers that emerged pushed her toward an archival study of fellow photographers’ work. Her effort aimed to recover the magic of the rituals that had been overlooked by so many directors and photographers who had approached the south with a detached, analytical “documentary gaze.” Rollo also noticed how regional rites had lost their original meaning for the communities that had created them. They had become commercial festivals, popular attractions devoid of their original purpose.

Thus, she embarked on a journey—with her Parallel Eyes—mapping out the origins of southern rituals, and documenting them in a way that highlighted the collective spirit of the community rather than the profit-driven aspects of their performance.

Many of the rituals had pagan origins, tied to the cycles of nature: fertility rites for the earth that happened at roughly the same time in different regions, on solstices and equinoxes. But Catholicism had absorbed many of these rituals, obscuring their connection to nature. In Apulia, for example, the “Focara”—which stands for “fire” and centers around a tall pyre—celebrates Sant'Antonio Abate on January 16. It coincides with the Campanacci in Basilicata, another rite of fertility and purification that once hinged on community life.

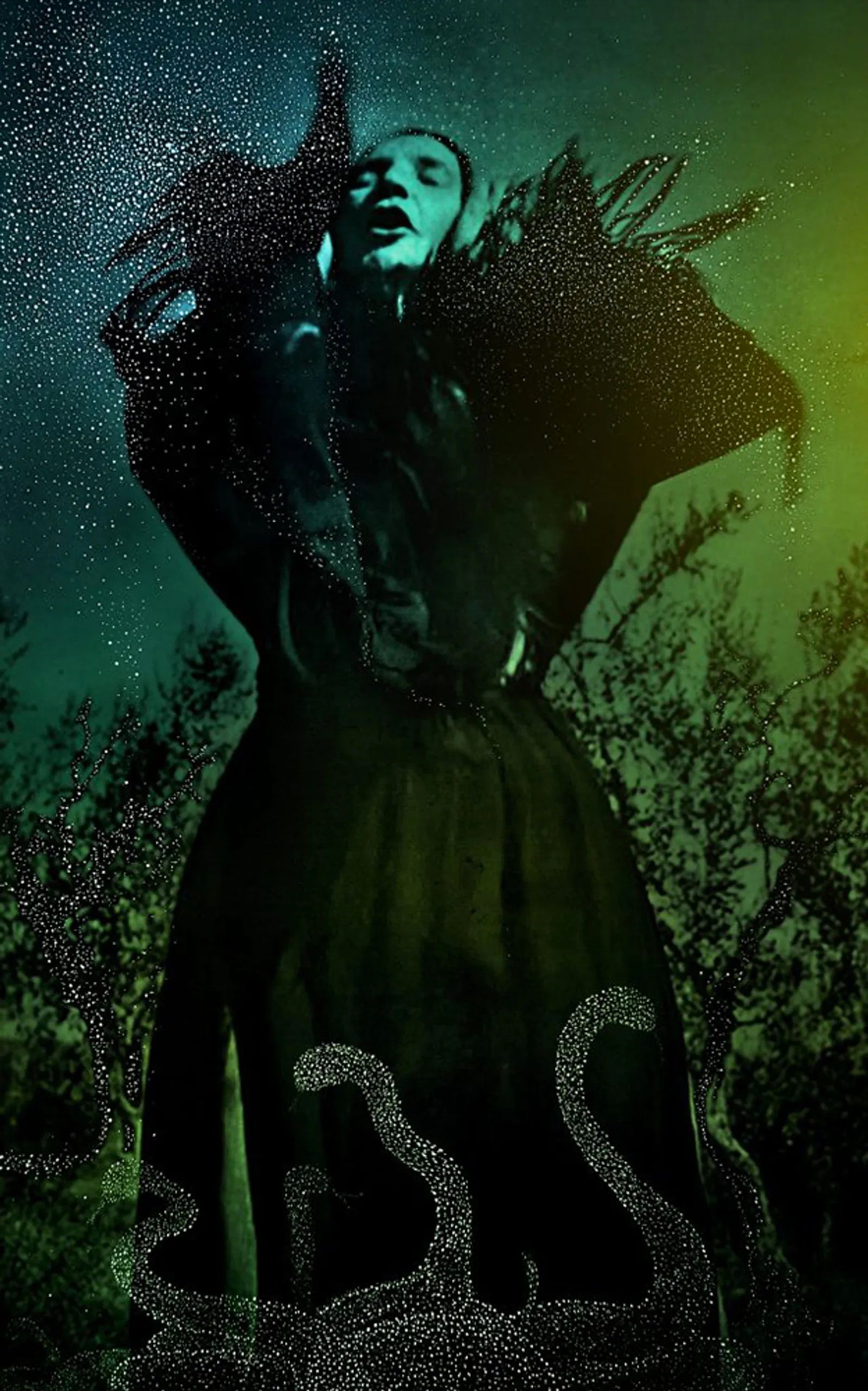

Among her many inspirations, Rollo studied the work of Ukrainian-American filmmaker Maya Deren, an avant-garde artist from the 1940s and ’50s. Deren belonged to a school of visual anthology that rebuked the documentary approach. As her Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti took shape, she abandoned the idea of documenting rituals because, she says, “rites exist” for those who have faith, but the camera inevitably fails to show what people “feel.” Echoing this sentiment, Rollo aims to show what people feel, beyond what’s visible to sightseers.

“That’s what I had felt too, [watching] these documentaries, as if they wanted to ‘prove’ something that had nothing to do with the community's need to perform the rites. I wanted to put into images what was not seen—this attention towards the invisible.”

In these numerous transformations, rituals become flattened. The “Notte della Taranta,” a regional dance from Apulia, loses its significance as it appeals to a community that is no longer its community of origin: it becomes a musical attraction whose roots are incomprehensible to tourists. “They don’t have an ‘anthropological interest’ in the rites of possession . . . [Visitors] come because it has become a huge festival,” Rollo says. “This is why the sense of these rituals has been lost.”

The rites were, for Rollo, aesthetic manifestations of a social structure that had been reduced to mere folklore. One of the many reasons, she explains, is that in the 1970s and ’80s, Italy yearned to prove itself as an important cog in the European machine, so there was an incentive to conceal the more ceremonial and traditional aspects that the south represented.

Major structural changes within society also fit the historical moment of industrial progress, contributing to the rituals’ disappearance. The introduction of factories led to industrial growth and the dissolution of peasant culture. Only recently has an appreciation emerged for the diverse microcultures that characterize these territories and their ancient rituals.

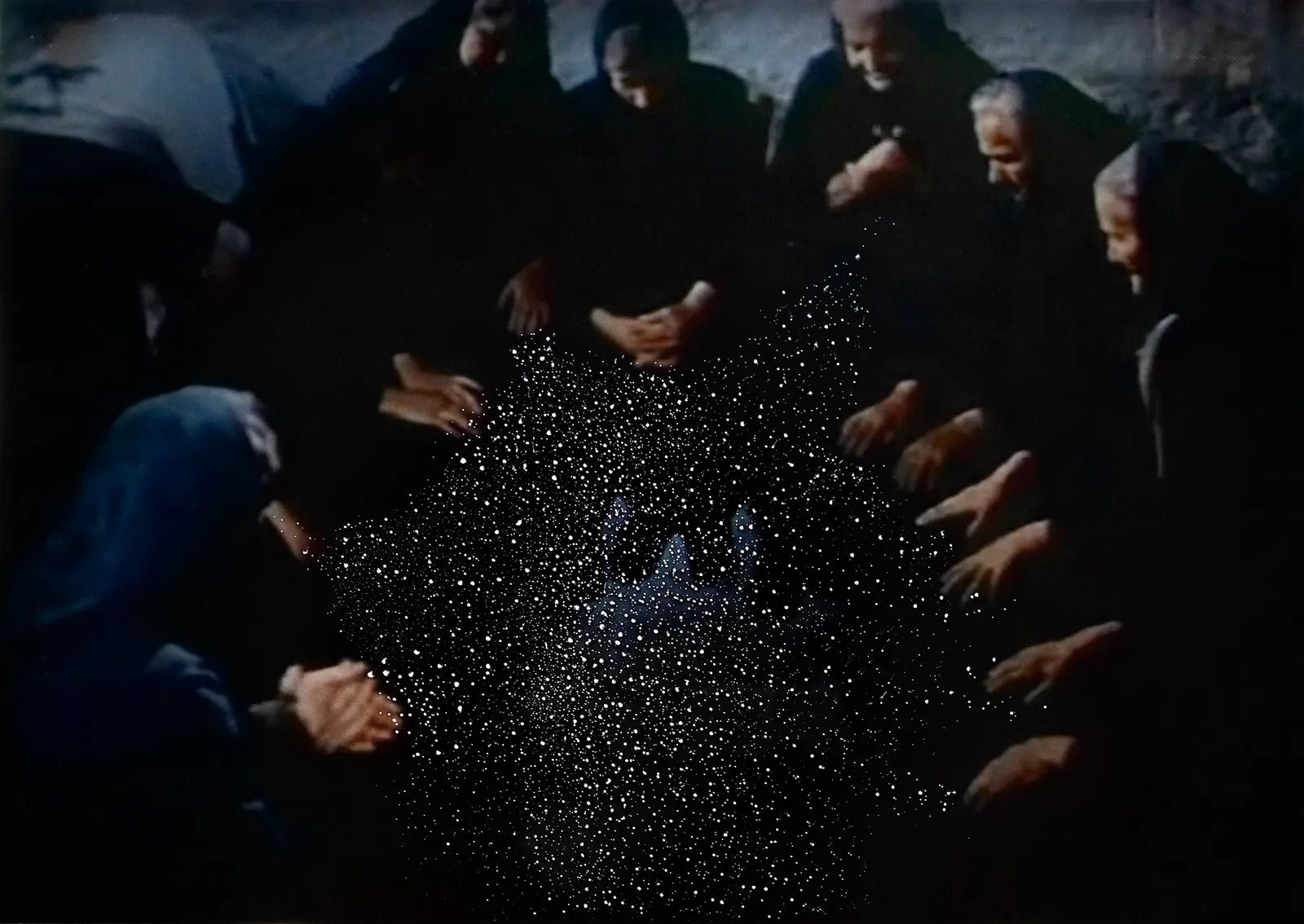

Looking at the works of authors who had played with the ambiguity of the photographic medium, Rollo began manipulating images, applying elements of analog and digital distortion, reintroducing “magical ritual” back into archival photos. When working on some images, she introduced symbols—water, fire, earth—elements that rekindle a connection to the essence of the rites.

For one image, she poked tiny holes in a light box to create a cascade of light. She describes this application as “creating another presence:” She added another dimension inside the image, and superimposed the two photographs.

The idea is to make a multimedia project in which different timeframes are present, an important aspect of rituals. “Time always comes back to the same moments, the same rites, the same manifestations, the same hierarchy within the rite.” Therefore, the lightboxes make manifest the circularity of time, she explains, and provide a layered perception.

This circularity is an important aspect of rites. In the last century throughout Italy, and more notably in the remote south, life has been marked by repetition—the same actions and habits performed again and again. This idea—inconvenient from a commercial perspective—has slowly disappeared, tarnishing the essence of the rites, their spiritual sense of devotion.

Take for instance the “Focara” mentioned above. Dating back more than 1,000 years, it has absorbed the winter solstice and requires thorough preparation and teamwork as olive branches and grape vines are cut and laboriously amassed into a pyre three stories high. The image of Sant'Antonio Abbate, placed at the center, is then set aflame and burns for several days.

The care that Rollo puts into the re-evaluation of the rites and their re-creation through images fosters an understanding and acceptance of different ways of living, bridging the cultural gap between north and south.

Those same customs that were once condemned, even rejected, have been reconsidered and turned into attractions: “Salento Lento”—a wordplay on the region’s name and the feeling of slowness—has now become a catchphrase where relaxation, once stigmatized, is now embraced. Moreover, Rollo feels that her commitment to chronicling the south can bring justice to an authentic narration of rituals, restoring their true essence.

“I would like to see other multifaceted views on this story, more personal and subjective, and less documentary,” Rollo says.

“I would like to take more courage and get [more] hands on this story, “ she continues. “I don't want things explained. I would like to ‘feel’ things. I would like this story to be open to many points of view because mine is just one. There are many stories within.”

All photos © Alessia Rollo, from the series Parallel Eyes

--------------

Alessia Rollo is a conceptual photographer based in Italy. Find her on Instagram and PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer focusing on photography, illustration, culture, and everything teens. She lives in New York. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.

--------------

This article is part of the series New Generation, a monthly column written by Lucia De Stefani, focusing on the most interesting emerging talents in our community.