When Monuments Become the Narrative

-

Published22 Jul 2020

-

Author

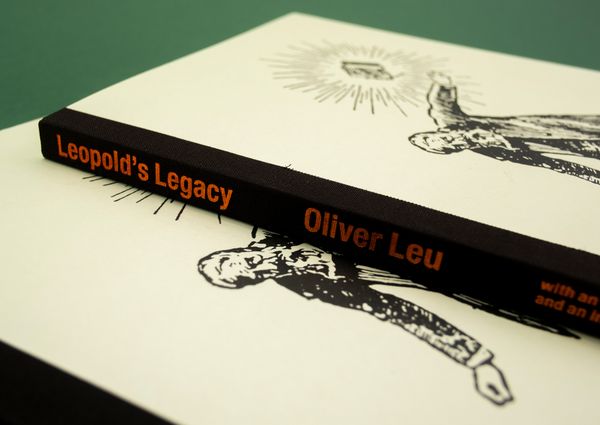

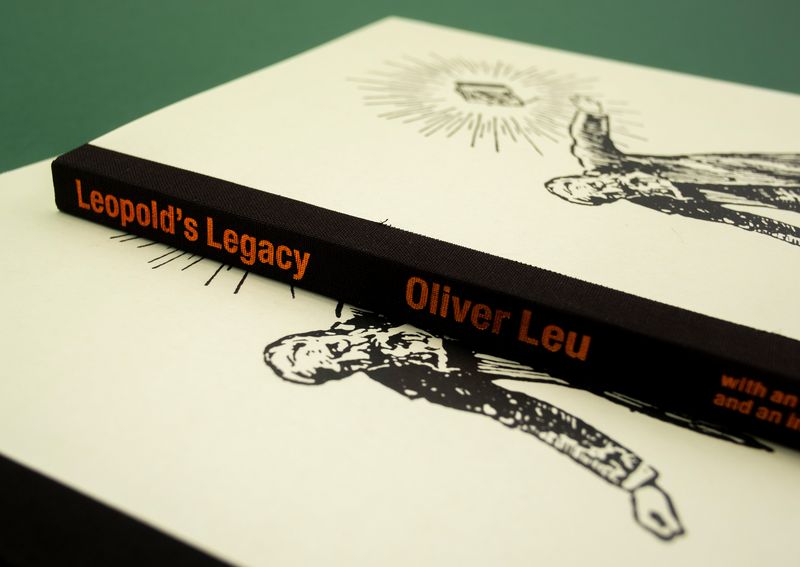

Leopold’s Legacy by Oliver Leu is the most timely of books. It details how Belgian monuments to empire sustain narratives that abdicate responsibility, divert blame, and ultimately deny Belgium’s role in the mutilation and murder of millions of people.

Leopold’s Legacy by Oliver Leu is the most timely of books. It details how Belgian monuments to empire sustain narratives that abdicate responsibility, divert blame, and ultimately deny Belgium’s role in the mutilation and murder of millions of people.

I live in Bath. It’s a beautiful city with beautiful architecture. Every year millions of visitors come to wander around its Georgian crescents and terraces, to soak in its hot-water springs, or visit its beautiful abbey.

It’s a town which since the 1700s has been a holiday town, a place of leisure and pleasure and easy decadence. You came to Bath when you had lost all ambition and just wanted to enjoy the pleasures of life. You still do.

You can wander around Bath and you will find histories of the Romans, the Georgians, the Victorians. You’ll find museums, churches, exhibits and houses dedicated to Austen, to Herschel, to Gainsborough, to fashion, work, and architecture. What you won’t find is so much as a mention as to where the money that built Bath came from, to the cast-iron connections it has to the slave-trade, to the sugar industry, to the suffering that funded the construction of so many beautifully designed honey-coloured buildings.

It’s part of our collective amnesia. We like to gloss over certain things, not even start to remember them. And if we do remember them, then we rationalise them. People had different values back then, it was a different time, there were different standards, they were killing each other anyway. And if that doesn’t quite stick, we conjure up the gifts we left behind. We look at India and highlight the civil service, the railways we built, the cricket we gave them. We take our lead from people like Bruce Gilley who wrote about how colonialism upheld ‘the primacy of human lives, universal values, and shared responsibilities’ and constituted a ‘civilizing mission” that ‘led to improvements in living conditions for most Third World peoples.’

Or we look to Niall Ferguson who wrote in 2013 that ‘no organization in history has done more to promote the free movement of goods, capital and labour than the British Empire.… And no organization has done more to impose Western norms of law, order and governance around the world.’

One thing we try not to do is let our true feelings show. That can be costly, as David Starkey found out in June this year when he said that ‘Slavery was not genocide otherwise there wouldn't be so many damn blacks in Africa or Britain would there? An awful lot of them survived.’ He has lost a lot of jobs in the week since he said that.

English rationalisations for empire are written into education, politics, and the church, but they are nothing to do with racism, we assure ourselves. They are to do with order, and economy, and helping infant nations develop and grow with Britannia as its caring nurturing guardian and protector.

And if anyone cares to argue to the contrary, well, we will say, at least we weren’t as bad as the French, who let’s face it are frightfully foreign. Or the Portuguese, look what happened to their possessions. And let’s not even mention the Belgians. They were absolute monsters. We can all agree and shake our head in horror at what the Belgians did in Congo. We’re not as bad as the Belgians!

Leopold’s Legacy by Oliver Leu is all about Belgium and Congo, the horrors that were inflicted there, and their airbrushing from Belgian history. The modestly sized book begins with a Contents Page that is a statement of intent, with eight chapters that examine the history, the memory, the monuments, the crimes, and the continuing presence of the empire in Belgium today.

The history of Congo is complex. Belgian involvement began with the establishment of the Congo Free State, a country privately ‘owned’ and run for the profit of King Leopold.

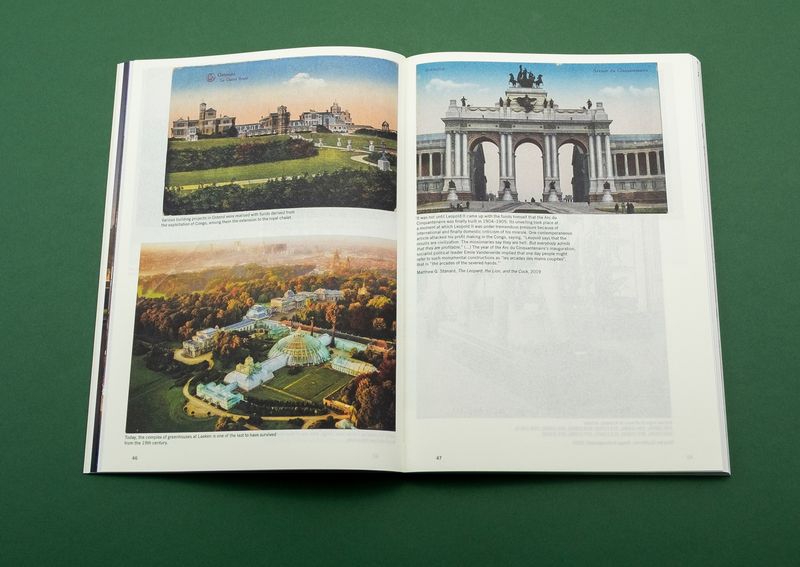

The Congo Free State became a byword for colonial horror, a slave colony where the inhabitants were forced to tap rubber for Leopold’s private gain, their forced labour both a ‘tax’ and part of the civilising influence that would break them away from their natural ‘indolence’. The population halved as starvation, kidnappings, and the amputation of the hands of people who didn’t fulfil their rubber quotas led to the population falling from maybe 20 million to 8 million in the period of Leopold’s rule.

It was a regime which led to one of the first campaigning uses of ‘atrocity photographs’ by Alice Seeley Harris. The most famous image shows a man called Nsala mournfully gazing at the amputated hand and foot of his 5-year-old daughter. She was killed along with her mother for failing to tap enough rubber.

Harris’s photographs were part of a campaign that helped lead to the death of the Congo Free State and the founding of the Belgian Congo in 1908, a colony that ‘endured’ until independence in 1960.

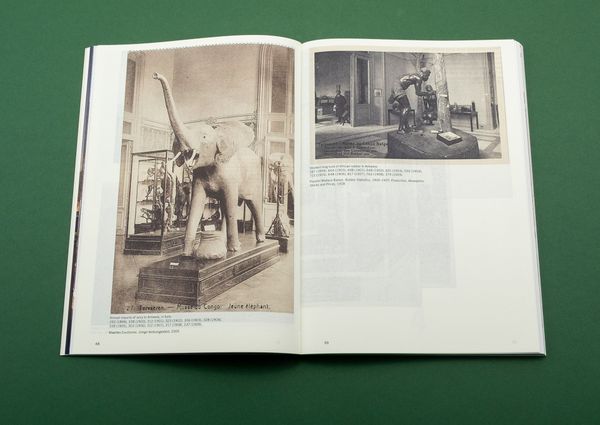

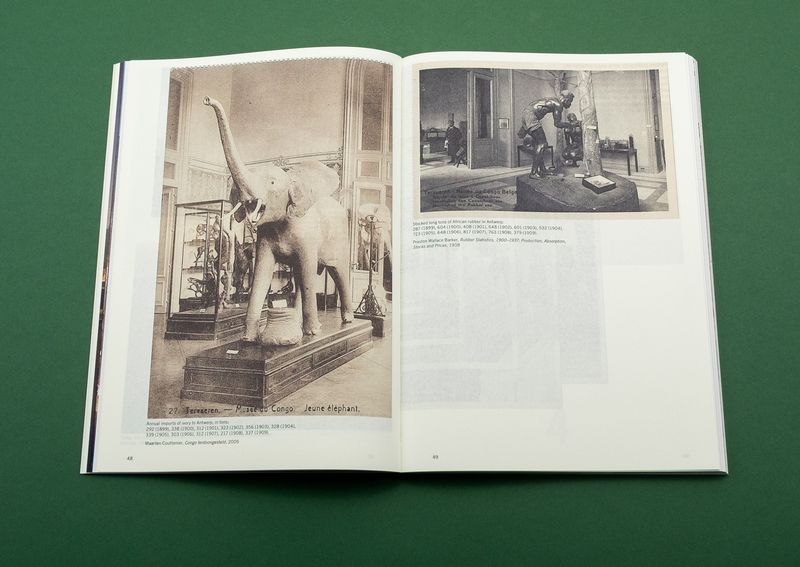

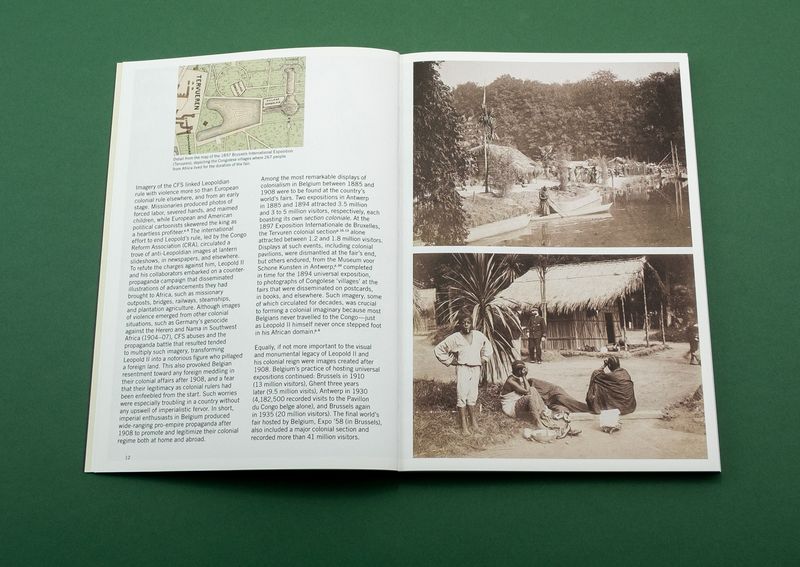

Leu’s book looks at the visual legacy of colonial rule. It includes archive images of Congolese villages recreated in Belgian for the 1897 Brussels International Exposition, and the coffins of seven Congolese who inhabited those model villages and subsequently died of tubercolis. They were buried in unconsecrated ground to the jeers of spectators.

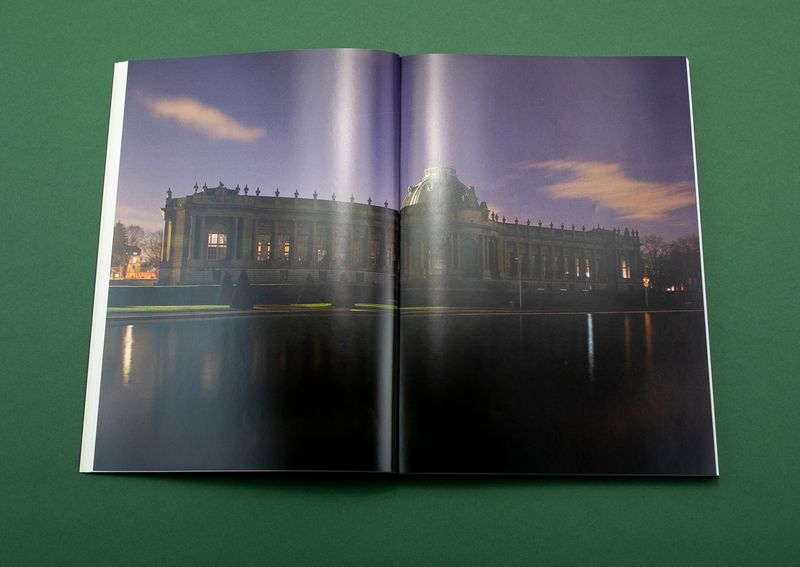

It shows the statues of Leopold II in contemporary images, in postcards, in archival photographs, statues that played a part in the resurrection of Leopold II, helping him go ‘from worst to first’.

There are also statues in which Congolese are shown as anonymous supplicating figures, symbols for ‘a conquered Africa or a conquered African people’, there to be rescued from Arab-Swahili slave traders and civilised by Leopold. These visual elements are part of what academic Bambi Ceuppens describes in her accompanying essay as ‘cloistered remembering; ‘cloistered memories’ are truncated, skewed and fragmentary, made up of legends and stereotypes, elaborated out of fear of telling the truth.’

This psychology of collective amnesia extends to the Belgian history of colonial rule (the one accessible book mentioned by Ceuppens is Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost), the continued recycling of colonial era propaganda photographs, and a polarised view of Leopold as either Empire-Building Saint, or Hand-Amputating Demon, a view in which Congolese become either ‘(grateful) receivers of the ‘civilisation’ or unfortunate victims…’

In both cases, there is no nuance to the story, no detail on the wider involvement of parliament, judiciary, and church in Belgian rule, nothing that enriches our emotional understanding of what happened to the millions who suffered and died. ‘What moves us are images, memories, music, objects, songs, sounds and statements that individualise victims and in doing so, allow us to identify with them.’

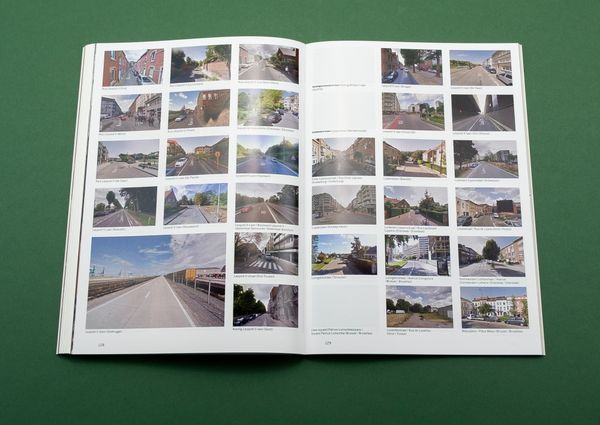

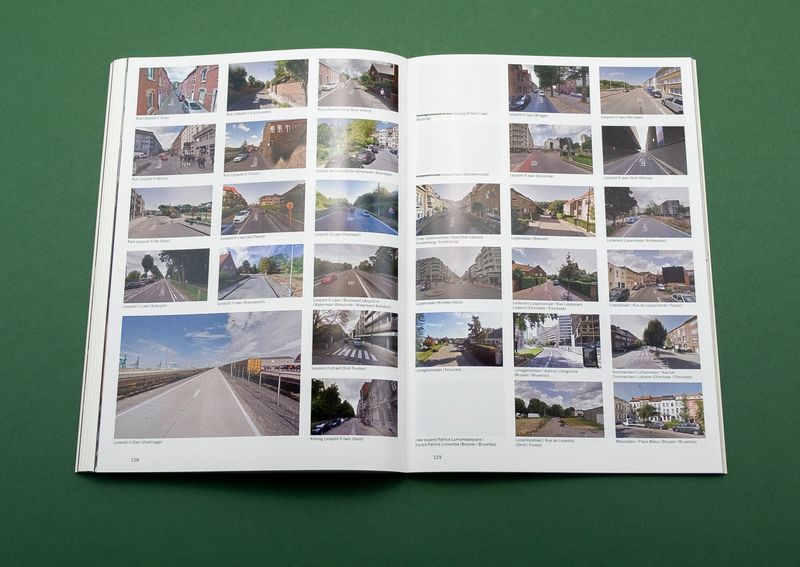

Leopold’s Legacy ends with images that reflect Belgium’s involvement in Congolese history; there are images of Lumumba, the assassinated leader of independent Congo, Leopold-centred collages, a series of screengrabs of colonially-named streets, images of monuments and statues that have had paint thrown over them, images that have Alice Seeley Harris’s atrocity photographs stuck to them, and statues have been modified to tell a story that would otherwise remain completely untold.

A week after Leopold’s Legacy arrived in the post, the Black Lives Matter demonstrations began. A week after that, the statue of Edward Colston, a former slave owner, was pulled off its plinth in Bristol and tossed into the harbour. The plinth now stands empty.

In towns and cities across Belgium, many of the statues and monuments that are re-remembered in this book have been removed, or marked, or repurposed in some way. In the UK, the argument was made that the removal of a statue was an erasure of history. The problem is people had been trying to get the history of Colston and his involvement in the slave trade remembered for years. They were blocked at every path. In Britain, we have great difficulty remembering our history.

The same is true in Belgium. To remember is difficult and takes time. It is a process which is complex and connects to narratives that extend from the personal to the political to the geographic. And that is what this book is about. It’s a remembrance that examines how these monuments, streets, and statues that honour ‘those who brought civilization to Congo’ are part of the ‘cloistered memories’ that deny history, responsibility and prop up a world view where one group of people is placed on a pedestal and another cowers beneath their feet. The monument becomes the narrative, and that is what Leopold’s Legacy makes abundantly clear.

--------------

Leopold's Legacy by Oliver Leu

Concept and photography by Oliver Leu // Essay by Bambi Ceuppens // Introduction by Matthew G. Standard

Design by Carel Fransen // Production by Jos Morree (Fine Books)

152 pages // 17 x 24 cm // €25

--------------

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His latest book, All Quiet on the Home Front, focuses on family, fatherhood and the landscape. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.