Healing Trauma Inherited from Previous Generations

-

Published25 Nov 2021

-

Author

The house looked very different now. Not so much in its structure, its rooms, or even its surroundings. What had changed was intangible.

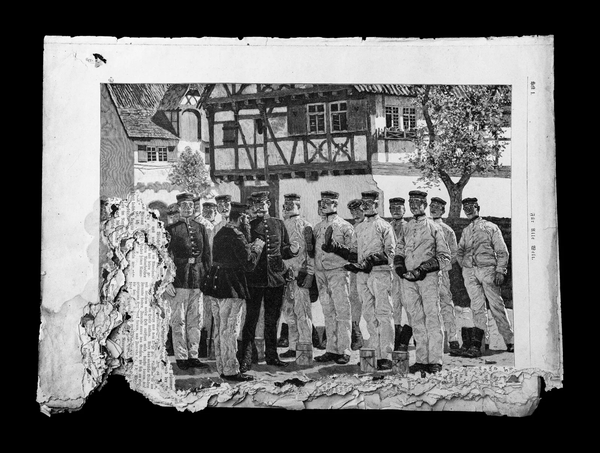

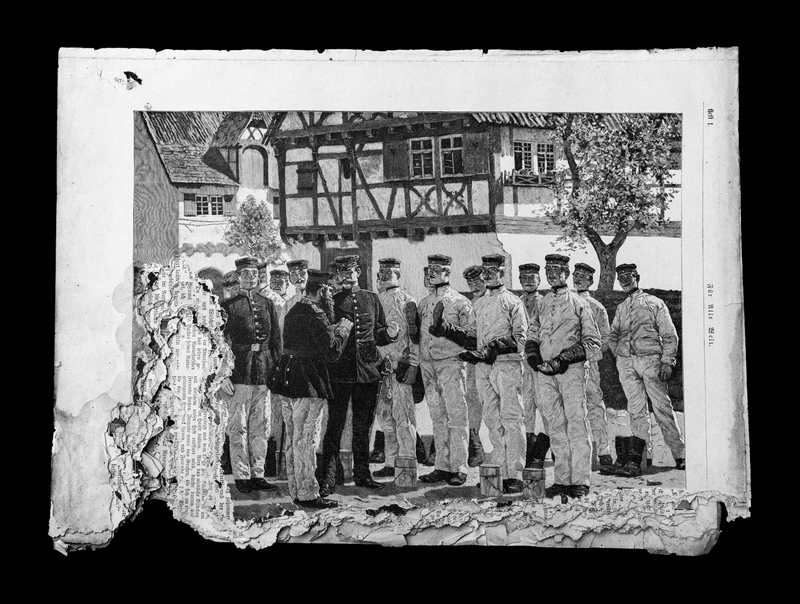

Her grandmother was no longer there—no longer on this earth—and her relationship with the house could no longer be the same. By revisiting these spaces, German photographer Elena Helfrecht evaluated her relationship with not only the family house, but also with her deceased grandmother, and what remained intertwined and suspended within their lives.

“I saw the house differently, which was essential for the series,” Helfrecht says of her work Plexus. Some geographical and emotional distance was needed to reconnect with these objects that were familiar yet unknown, in search of underlying meanings.

In Plexus, Helfrecht reflects on the shared experiences of generations, and how trauma passes from one generation to the next, as seems to have happened in her family too, from her grandmother to her mother to herself. A pattern, though, that is sometimes necessary to break, a hole that can be closed. “These wounds can be healed if you take care of them, if you nurse them,” Helfrecht says, “otherwise they stay open and grow worse, get infected, and devour you.”

Through a lengthy practice of self-analysis, Helfrecht discovered the main objective of Plexus: “to really make those psychological processes of inherited trauma visible, to visualize what can actually not be grasped or seen,” Helfrecht says. “I believe you can only confront and fight what has a material form, and therefore you must define it first.”

Starting with stories from her own life, she distilled their “essence” in order to transcend her personal experience and open the imagery to multiple interpretations. Her goal was to make space for the “inheritance of trauma” and “postmemory”—a memory not experienced directly but one that leaves an impression so vivid that it becomes a memory of its own—accessible to the viewer on an emotional plane.

Inevitably, one’s personal history intertwines with the broader history of one’s nation, as happened for many members of her generation in Germany, whose past still echoes with painful memories. To some degree, however, this resonance goes beyond geographical borders. “These processes by which trauma is passed on are always similar,” Helfrecht says. “National backgrounds don't matter anymore, no matter where you come from. The way you're impacted is always the same and always shared, something that connects us all across borders.”

We enter her family house and her analytical perspective by stepping into the attic. In the image she took of that room, a spotlight projects a sharp circle of light. As the eyes adjust to the shadowy space beneath the roof, “things come to light”—just as the mind gradually grows conscious of its situation.

Helfrecht drew some inspiration from French philosopher Gaston Bachelard’s book “The Poetics of Space,” in which parts of a house are associated with aspects of human consciousness. The cellar, for him, is a place of unconsciousness, a space where we may confront our fears. The attic is where things come to light.

Coiled around a miniature wooden house, the bodies of three snakes intertwine and twist—arousing perhaps such emotions. The image is based on a recurring dream, but Helfrecht points out that its sense remains open to interpretation.

Helfrecht creates subtle links between the images she captures and the titles she chooses, adding a layer of meaning without forcing an explanation. She pushes the image into purposeful ambiguity to trigger the viewer's imagination. The titles serve to spark viewers’ intuitions, she explains. “What I depict and show is not what it seems. I photograph one thing, but I mean another—it becomes a symbol for something else.”

Here again, an unequivocal meaning is lost to multiple readings; the snake symbolizes evil for one culture but wisdom for another. By changing its skin, the serpent also renews itself, a cycle of new beginnings similar to familiar patterns that recur throughout history. Helfrecht allows such symbolism to surface naturally. “The symbols have often emerged all by themselves. I have not sought them out, I have just photographed.”

In her work, an important role is played by animals—particularly birds. For decades, her grandfather kept pigeons; her grandmother had geese and chickens. Poultry was part of the natural cycle of living and sustenance for the family. “These animals were always accompanying the people of the house and were living here for generations. There was always this constant circle of life and death.”

In another image, a moth has found its final place of rest in a teacup filled to the brim, its wings dampened and therefore ruined. The crease in the tablecloth aligns with the border between light and shadow that is reflected in the calm surface of the liquid. The image compels us to ponder duality in life, different possibilities and different outcomes. But the cup of tea also invites us to quietly reflect. Out of the many possible interpretations, Helfrecht offers a personal one: “It represents the sort of silence in which traumatic events are shrouded,” she says. “This generation and the generation of our grandparents is a generation that is very silent about these events…. It's very hard to talk about this, [but] it's our duty to break the silence,” she says. And a cup of tea, served in fine porcelain, becomes a symbol of sitting together, a symbol of this important conversation to have.

--------------

All photos © Elena Helfrecht, from the series Plexus

--------------

Elena Helfrecht is a German visual artist working with photography. Her work revolves around the inner space and the phenomena of consciousness, emerging from an autobiographical context and opening up to the surreal and fantastic, at times grotesque. Interweaving memories, experiences, and imagination, she creates inextricable narratives with multiple layers of meaning. Find her on PHmuseum and Instagram

Lucia De Stefani is a writer focusing on photography, illustration, culture, and everything teens. She lives in New York. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.

--------------

This article is part of the series New Generation, a monthly column written by Lucia De Stefani, focusing on the most interesting emerging talents in our community.