Everything Precious Is Fragile: Interview with Azu Nwagbogu, Curator of the First Benin Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

-

Published16 Apr 2024

-

Author

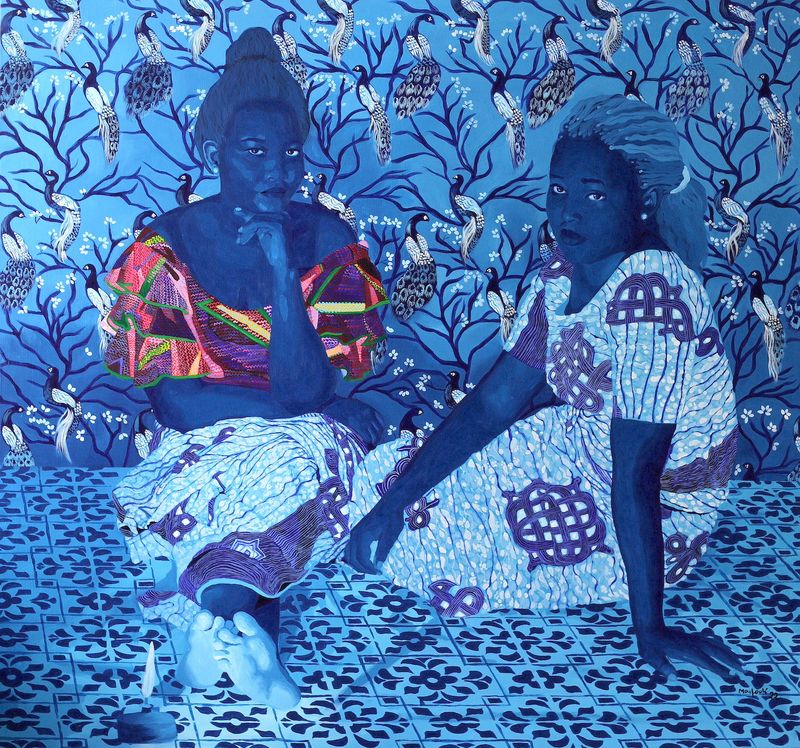

Bringing together Ishola Akpo, Romuald Hazoumè, Moufouli Bello and Chloé Quenum's works, Everything Precious Is Fragile embodies the unfinished and the suspended, the vulnerable and the incomplete to express a story of post-colonial restoration.

The first pavilion ever presented by the Republic of Benin in Venice has a delicate equilibrium at its foundations. Between the four works on show, whose completeness is only accomplished when seen as a whole. Between the urge to restore indigenous knowledge and the will to create a dialogue with the existing, Western structures of the art world. Between contemporary art, photography, and design.

Founder and director of the African Artists’ Foundation and LagosPhoto Festival, curator Azu Nwagbogu walked us through the feminist, ecological ideas nourishing Everything Precious Is Fragile, with concepts of restitution, repatriation, and re-balancing at its core.

If you look back at your practice until today, what do you think are the steps that brought you where you are now, curator of the first-ever Benin Pavilion in Venice?

I was the middle child in a family of 9 siblings, where everyone had diverse talents and interests. I have always thought that my role was to connect generations and bring people together. That’s what I’ve always done as a curator – all of my research is about creating harmony and synergy. But also, as you get aware of the way the world has been constructed to keep other people out, you realize what the strong political aspects of your job are. Breaking those barriers is what, I believe, I’ve been working towards all these years.

How did you come to the title Everything Precious Is Fragile, and what does it mean for you?

I was doing research in Benin, interviewing the custodians of culture, who are the traditional rulers. I wanted to know their thoughts about the history of Benin. Benin has a kind of a dark past because of the slave trade: statistics describe that between 30 and 40 percent of enslaved people from West Africa were shipped out of Ouidah. Unlike other African countries, the residues of those atrocious events are quite evident. I also wanted to discuss why Africa, the cradle of civilization, is sort of lagging in its contribution to the arts, politics, technology, philosophy… why is it that we have migrations, too? I asked them questions about all of these issues.

They trace the causes in the way women were removed from their position of equality in society. The Earth is a mother, the Earth is feminine: for ecology and nature to come back into order, we need to restore that balance. During the interview we spoke about Gelede, a philosophical feminist movement. One of the custodians told me its etymology translates to: everything precious is fragile. This comes from an apocryphal story of a very wealthy, influential man who dismissed a bunch of children who were playing with the Gelede mask, dancing and making noise. After this episode, the gods made him sick – they were displeased, as the children were praising and honoring them. He then confronted a horacle, who said to him: everything precious is fragile. Your life is precious, and it is fragile. So you should be careful of how you communicate, and of the words you use.

In Africa you don’t just pluck a tree, or a leaf, or kill an animal. You say a prayer before you do that. It’s not about just respecting human life, but about respecting all life and its secretiveness.

Listening to him, I said to myself: “Wow, ok – that is going to be the theme”. It encompasses issues of diversity, ecology, charity, family… all of these things that are precious and fragile and that we dismiss today, in our relentless quest for capitalistic profit.

How have you brought fragility to the way you conceived this exhibition?

I believe that once you put yourself in a vulnerable position, not trying to protect yourself, you can feel more. Each of the artists I’ve selected made themselves a little bit more vulnerable, as there isn’t one complete work in the pavillon. We have four artists, but not four solo exhibitions: they are one of four, and two of four, and three of four, and four of four. They all made incomplete work that fits the whole. Their fragility is in trusting the process, in accepting to have an idea, but not giving it fully, leaving something out. They all sing the same tune, but in different notes.

Fragility is in materiality, too: the Gelede mask sculpture was made in Murano. Not many people know that Venetians learnt to make glass from Senegal. Glass is a very interesting object – it has such an incredible ancient history, it is very fragile and transparent. Its materiality can tackle many of the thematic problems we are dealing with today: climate change, biodiversity, the way society has become increasingly more suspended. And the way knowledge and memory are so fragile, too.

Colonial, hierarchical structures are so embedded in the way art has always been shown and talked about in the Western world. Is this something you came across, wanting to challenge those same structures through your practice?

I believe in not playing the victim. Existing structures can either be destroyed, or transformed. You can destroy Babylon or you can go in there, change its architecture, and the intelligence that made it stand. It’s iconoclasm or reflection. We are here now in Venice. Twenty years ago, there were not many African Pavilions here. Now, the neighboring Pavilions are Albania and Senegal. During the 1884 Berlin conference which cut Africa out, there wasn’t one African in the room. For four months, a bunch of Europeans were making decisions, with only two of them having ever stepped foot in Africa. There is now the opportunity to have a dialogue, and we should never not find a space for that.

What is your relationship with Benin?

I come from Nigeria, which is a neighboring country. Before colonial times, when these absurd nation-states were created, there was no distinction between Benin and Nigeria. My practice, my religion, my belief is Pan-Africanism – I believe in a united Africa. People speak the same language in Benin and in Nigeria.

About Benin more specifically, its leadership has taken a strong stance in shaping a new identity through arts and culture. And I feel all African countries can really learn from this.

Looking at your experience as the founder of LagosPhoto, what do you think of the relationship between photography and contemporary art? What role does it play in your practice?

I believe that photography and design are the pillars of contemporary art. Photography has a wonderful quality: it illuminates things. It clarifies anything that it turns its lens upon. In my work within contemporary arts, photography is a natural way for me to think. It is a language everybody can understand and relate to, it is the most transmittable art form. I see a lot of curators who do not consider it, and I can see there is a difference in the way they work and think. This process is so slow because photography suffers from a paradox: it can be used as evidence and documentation. But you know, in life all great truths have a paradox in them.

Can you guide us through the four works exhibited in Everything Precious Is Fragile?

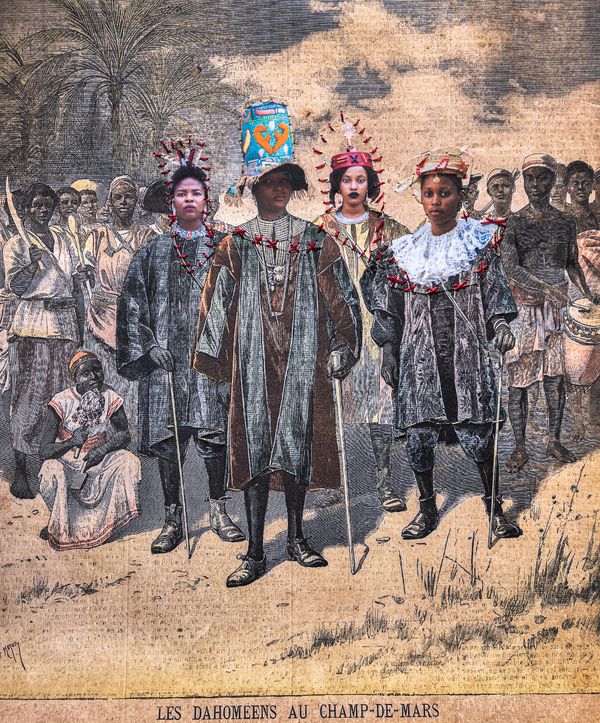

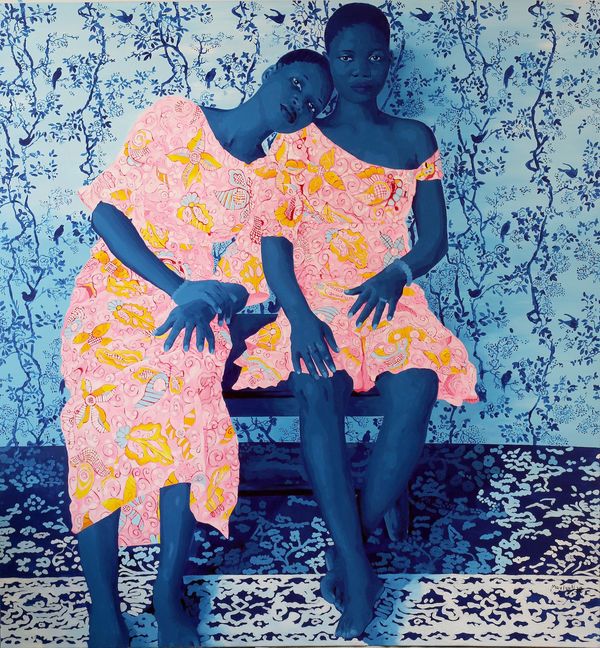

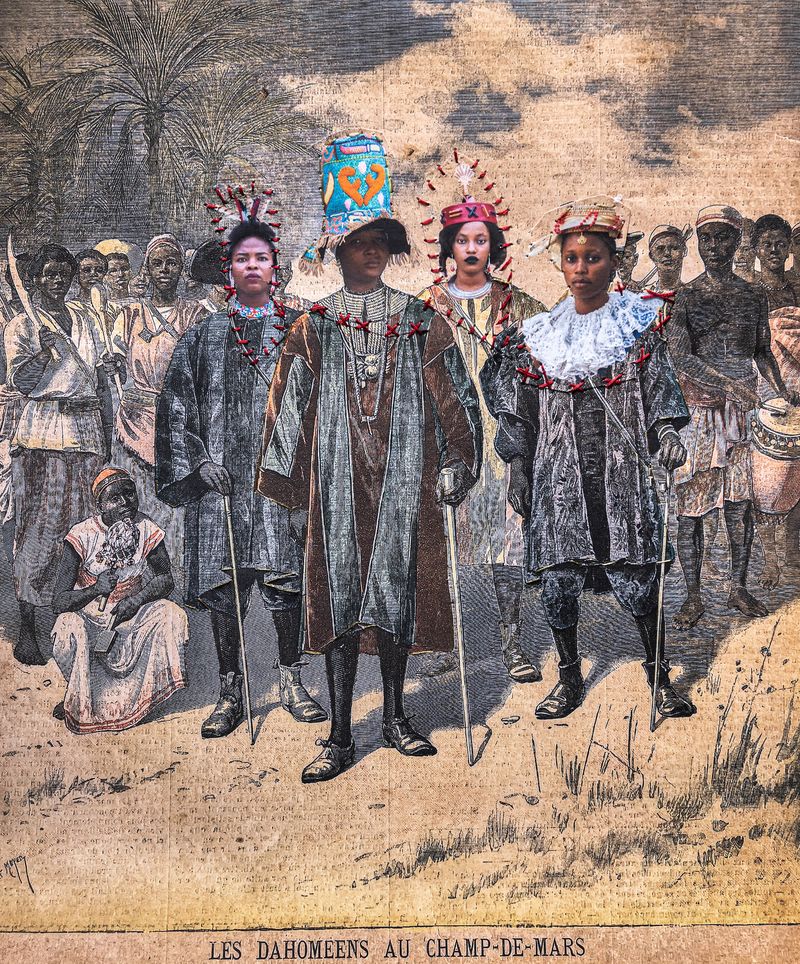

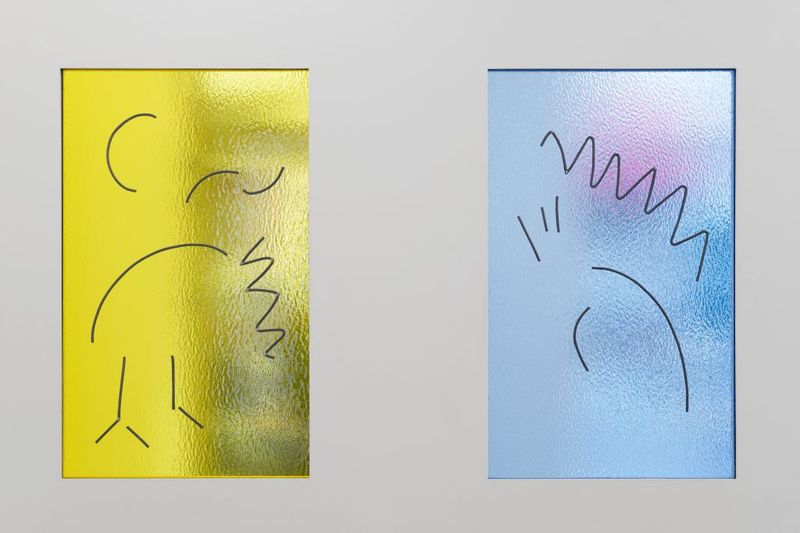

All the four artists work with photography, whether it is a tool for documentation, for research, or the way they present their work. We have Ishola Akpo, who delves into Benin’s archival material representing women and into the role they cover in positions of authority. Moufouli Bello is creating a sort of visual archive of the history of Benin drawing on the Gelede feminist philosophy, and she’s also putting together a library called the Library of Resistance – an attempt at capturing the history of women’s thought through publishing. Chloé Quenum reflects on the architecture of the Arsenale, its rules and history, and she works around objects photographed in museums in Europe which have been taken out of Africa. Romuald Hazoumè gives shape to a cathedral, creating a moment where we can come together.

What was the process leading you to come down to these four names?

It wasn’t easy. There were a few obvious choices, people I knew I needed if I wanted to work in a certain way. But as I really aimed to create something that wasn’t individualistic, I had to research to understand who would be able to carry this humility of giving up space, while understanding the bigger picture. I believe that everything you do, you should do with more time, with more care. A little extra, my dad used to say, makes a genius. So obviously you have an idea of the direction things will take, but you should just give it a bit more time. The title of this exhibition came from the very last visit that I made to Benin. To really do the job, you have to dig deep.

--------------

Biennale Arte 2024 runs in Venice from until 20/04 to 24/11/2024.

--------------

Azu Nwagbogu is the founder and director of the African Artists’ Foundation (AAF), a non-profit organization based in Lagos, Nigeria. He is also the founder and director of the LagosPhoto Festival, an annual international photography festival held in Lagos. He is the editor of Art Base Africa, a virtual space for discovering and learning about contemporary art from Africa and beyond. In 2021, Nwagbogu was awarded the title of «Curator of the Year 2021» by the Royal Photographic Society in the United Kingdom, and was also ranked among the one hundred most influential people in the art world by ArtReview. In 2021, Nwagbogu launched the project “Dig Where You Stand (DWYS) – From Coast to Coast”, which proposes a new model of institutional construction and engagement, raising issues of decolonisation, restitution, and repatriation. The exhibition took place at Ibrahim Mahama’s Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) in Tamale, Ghana. More recently, in 2023, the National Geographic Society named Nwagbogu “Explorer at Large”, making him an ambassador for the organisation who will benefit from support to continue his storytelling work in Africa and throughout the world.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based between Italy and The Netherlands, graduated from MA Information Design at Design Academy Eindhoven (NL). Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.