The Last Time I Agreed to Dress in the Same Way as My Sister

-

Published10 Jun 2020

-

Author

Two identically dressed sisters, a three-year age gap, and a compulsion to make the sisters dress the same. That’s the puzzle contained in Eliane Heuser’s Betty e Eu.

Two identically dressed sisters, a three-year age gap, and a compulsion to make the sisters dress the same. That’s the puzzle contained in Eliane Heuser’s Betty e Eu.

There is a whole slew of photobooks and projects about family, about the archive, about parental or ancestral histories. There are books that try to make sense of who a person was, there are books where the images found are used to redefine an identity, to provide the author with a grasp of who a person used to be, or simply to create an alternative vision of who they might once have been.

Books like Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home provide a multi-layered perspective of who his parents are, the conflicting accounts of their relationship, and how their personal lives were entwined with the social, cultural, and corporate transformations of the late 20th century.

Maria Kapajeva’s You can call him another man invites the viewer to fictionalise her father through images from the time before he met her mother. In a different way, Caroline Furneaux’s The mothers I might have had uses old slides her father took of his girlfriends to imagine who her father might have been.

All these books work on the idea that images are not fossilised entities, that visual histories are flexible and fluid, that when we view a family album, we very easily stray from any one fixed narrative, because there isn’t one fixed narrative.

The classic idea of the family album photograph that gets repeated again and again is that they are there to mythologise an idealised family, to show enjoyed holidays, meals, and celebrations with all the family happily gathered around.

There’s that but then there are the cracks where the family neuroses emerge. That’s both down to the generosity of the image; there are places where the oddness and obsessions of a family inevitably peek through, either accidentally or deliberately.

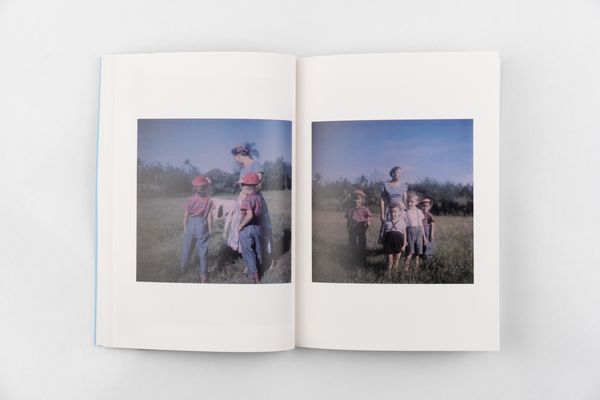

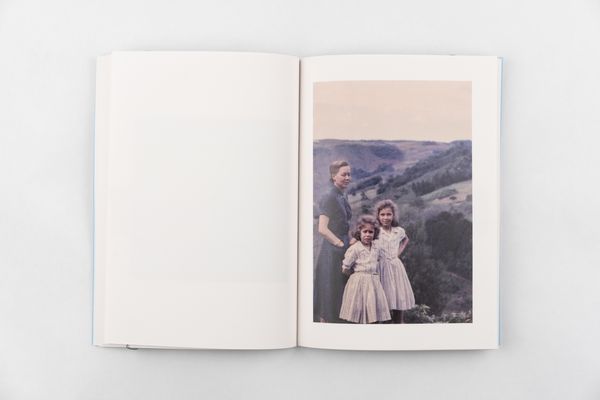

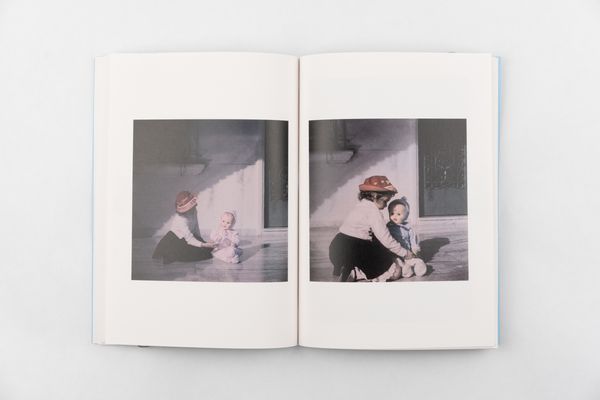

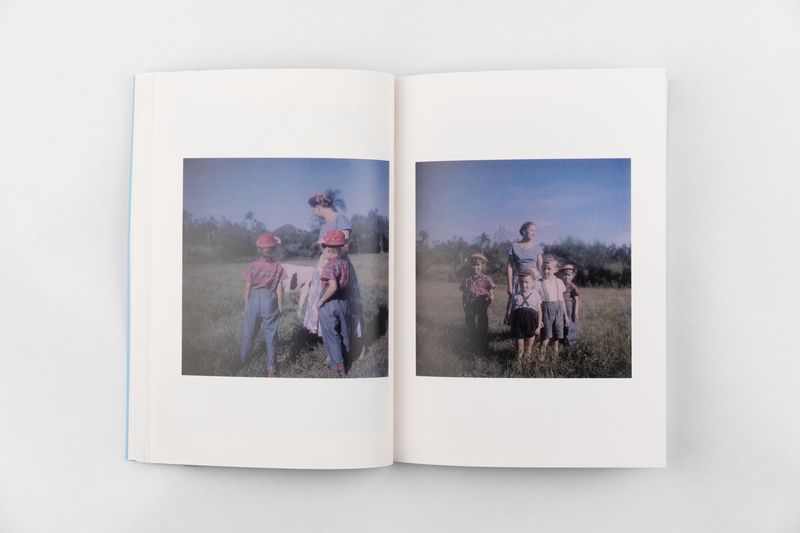

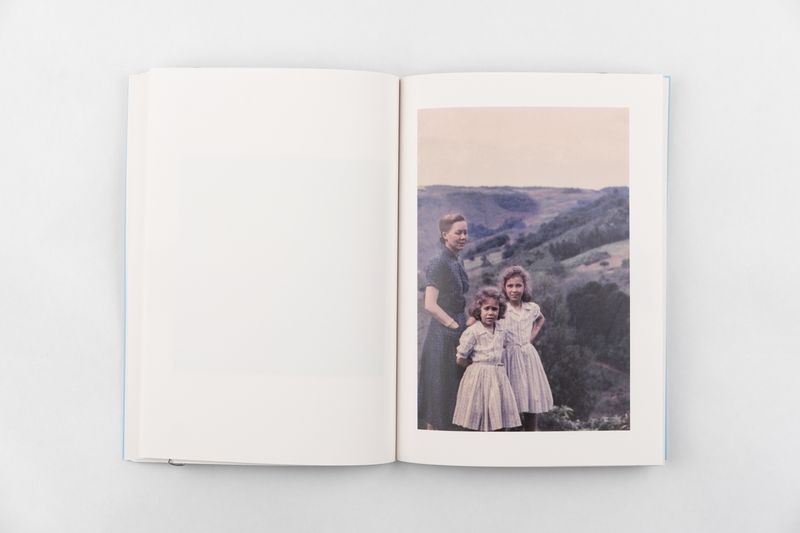

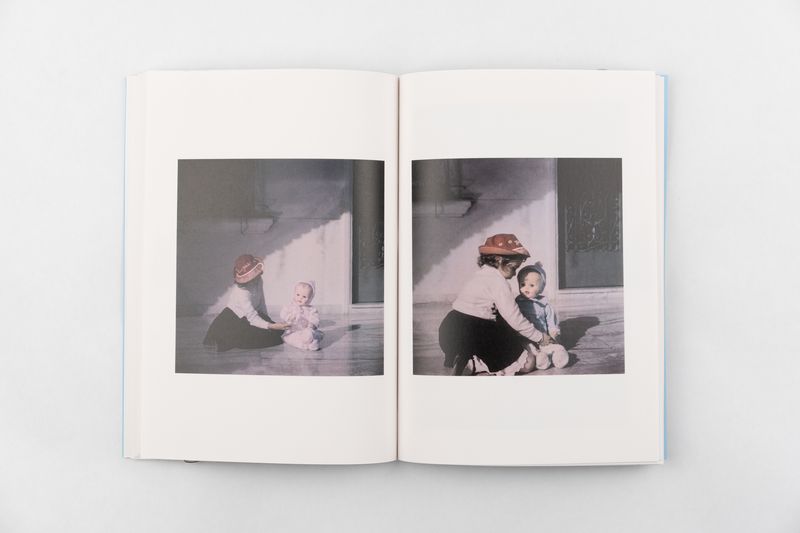

And that’s kind of the point of Betty e Eu. It’s a book of pictures of Betty with her sister Eliane, the author. Betty is three years older than Eliane, and the book starts with the two of them standing side by side on a tiled path, manicured lawn with curled hosepipe snaking behind them. They are both wearing identical three-quarter sleeved v-neck jumpers, pleated knee-length cream skirts, and white pumps.

They’re dressed like twins. And that’s what the book features, pictures of Betty and Eliane dressed alike; at home, with a tapir at the zoo, in the rockpools by the sea, by a babbling stream, in front of an apartment building, on a farm, in a field. And wherever they go, they wear the same thing.

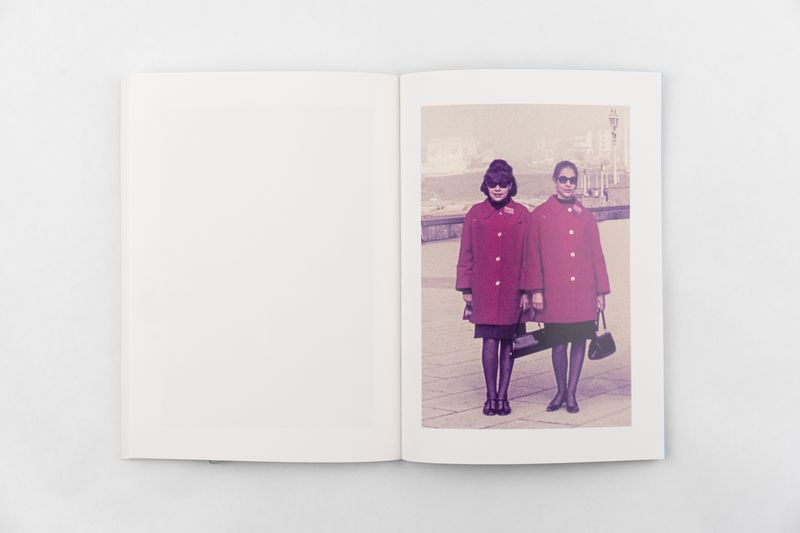

The final picture shows them as adults wearing fuchsia coats and sunglasses, black handbags and black silk stockings.

Why they’re wearing these similar clothes we are only left to guess. Is it the younger Eliane looking up to her older sister? Is it some kind of sibling identification. We don’t know because there’s no text in the book. So we submerge ourselves in the pleasure of looking. That’s the remnant of the album that we get, the pleasure of looking at these jumpers, and dresses and skirts in an upper-middle class Brazilian setting.

There’s another little bit of text that is on the Photoireland website (and it should be in the book. Just as a one-liner) that changes everything. ‘The last photograph in the series,’ writes Heuser, ‘depicts the last time I agreed to dress in the same way as my sister,’

It’s an odd thing to read, it’s an odd thing to happen, and it changes how we see these images of likeness. The idea that this was all the younger Eliane’s doing goes out the window, and instead we are stuck with a neurosis, a desire for one child to dress like the other. Instead, we are left to wonder who these dressing up orders came from? Were they from the parents or the sister? Was there some strange twin obsession being played out in these pictures, were these pictures perhaps a result of some earlier loss in the mother’s life. Or were they an attempt to make one child conform to the other’s behaviour, demeanour, appearance, or tidiness. Is it a question of making Eliane be more like Betty, and if so how? Where did this come from? The parents or Betty? Or someone else?When we see the title, Betty e Eu, the perspective shifts to the sister. The sister who made her sister dress identically, or the sister who was the preferred child? And so we are on another path and we are searching for clues for why this might happen, for how ‘…the way we dress refers to a desired and imposed equality’ as Heuser writes.

The disappointment and sorrow of childhood is embedded in these pictures, and that’s the puzzle of the book. We are invited to fictionalise this relationship, to read the poses, gestures and glances, and wonder at how and why this dressing game took hold, the how and why of this sororal relationship. Who is smarter, prettier, more graceful, and socially adept. Who is awkward, difficult, angry, or confused?

There's the idea that the family album is much more than a simple collection of photographs (partly because almost no collection of photographs is a simple collection). It's a localised family ideal wrapped up in images, it's a fantasy of who you'd like your family to be, it's an act of mimicry, it's a ritual, it's a collection of ritualised encounters, it's a site of your childhood alienation, it's concealed dysfunction, and then it's an object in itself, part of the house, or room, or box to which it belongs.

But most of all it’s a disguise, and it’s a very visible disguise. Betty e Eu is a disguise and we are left to guess at what lies beneath that disguise, what disappointments, what mouldings, what neuroses, what resistance. It’s in there somewhere. You only have to look. And you might be wrong. But when did that ever matter?

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His latest book, All Quiet on the Home Front, focuses on family, fatherhood and the landscape. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.