Bolivian Women Fighting Social Discrimination

-

Published10 Apr 2020

-

Author

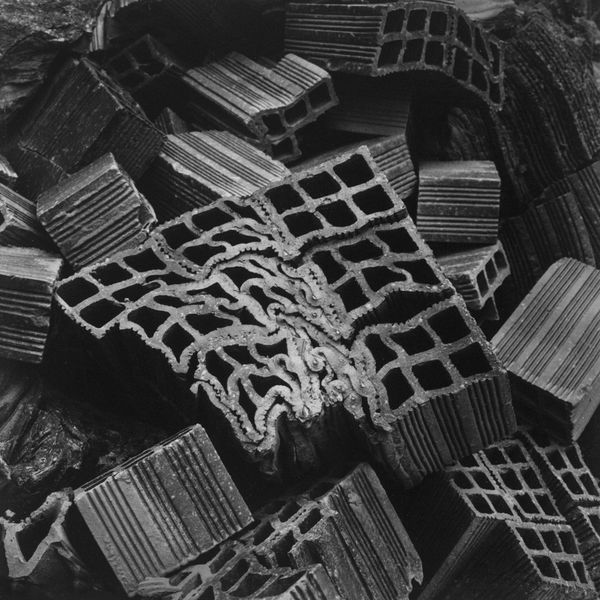

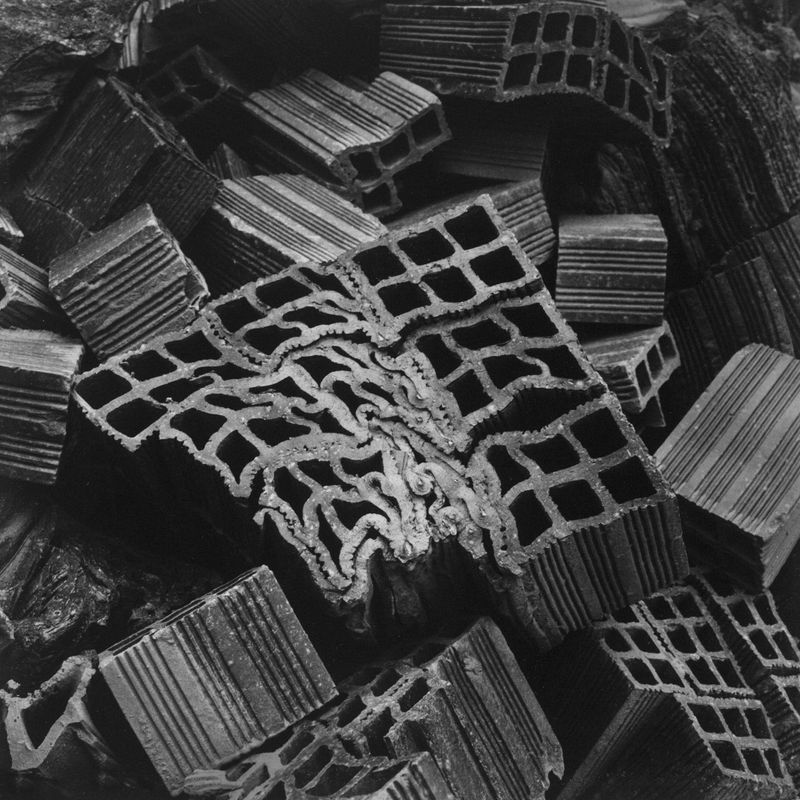

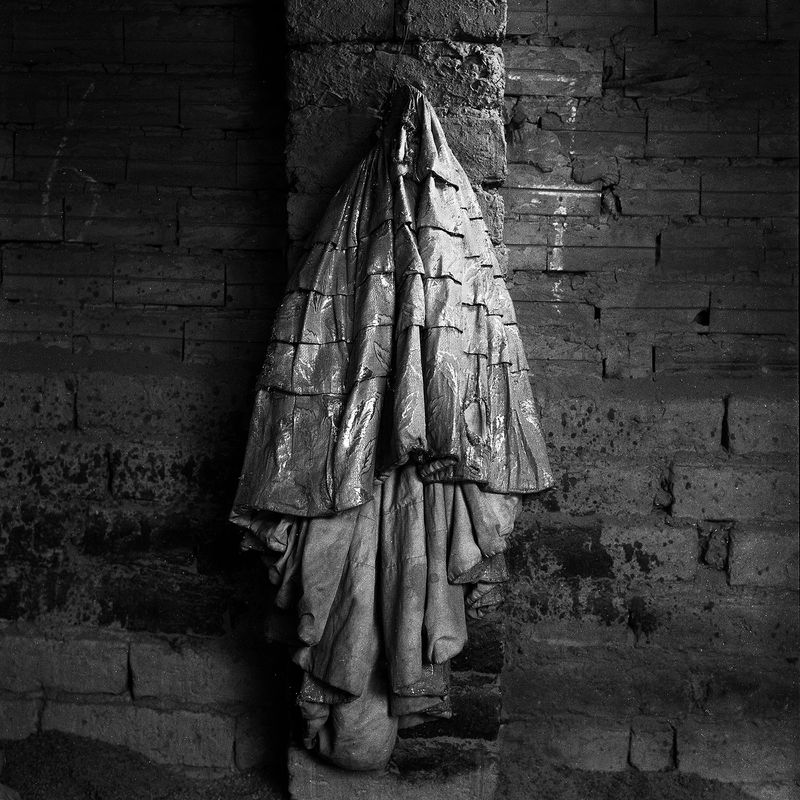

Sofía Bensadon portrays the women behind Bolivia’s construction industry. By documenting their work and recording their testimonies, she looks to capture their resilience and determination despite the marginalisation they are subjected to.

Since the Chaco war in Bolivia real-estate development has been evolving, especially during Evo Morales presidential period. As a result of this rapid demand, today many women have joined the construction industry in their country. In La Paz and Alto, it is socially questioned that women have joined this traditionally male expected labour. Despite social discrimination Bolivian women have continued to work in the field and gained their work pal and family members respect. Bensadon inspired by her father’s traditional views on construction’s sites, she embarked on this ongoing personal project that looks to give a voice to Bolivia’s resilient women.

What first motivated you to work on your series 50KG about female workers in the construction industry?

The sounds of hammering and shovelling were the lullabies that would send me to sleep during my afternoon siestas as a child. The construction industry is part of my family’s everyday life. However, it wasn’t until I was working as a photographer for a construction company that I had the opportunity to be part of it, instead of observing from the distance. Up until that point, I would always think about something my father once said: “Construction sites are a no woman’s land; a dangerous place for a woman.”

In 2015, I created “Behind the Frame”, a photographic essay that documents different encounters with masons on a construction site in Buenos Aires, Argentina. This experience led me to Bolivia after a group of Bolivian workmen said to me in passing: “In our country, women work in construction”. In January 2016, I decided to travel to the city of La Paz, Bolivia to meet these women who were working in a work field that is historically a man’s world in my country. For me, it challenged what my father had once said and that motivated me to capture it.

Could you talk about the title of the series?

The 50KG cement bag represents one of the central elements of construction sites when measuring the skills of workers, especially strength. The salary of an assistant, for example, suffers discrimination by gender for not “performing” in the same way when it comes to moving the cement bags. That is "the excuse" that employers use. Not being able to easily carry that bag, makes women be seen as less profitable for this job. The weight of this element creates a problem, a challenge, an abuse, an ambiguity, when it comes to thinking about strength and working with bodies in construction.

I use the weight of the cement bag as a title to indirectly introduce a question about the empirical construction of force. Through this trans-media project, I am interested in exploring the different profiles that construction women experience in Bolivia. A "force" that from the body will find many forms, and from their stories, it seems that it is not only physical force. With this project by using the tools of anthropology and audio-visual I am trying to problematise the notion of strength between women and men that affect different spaces of our life. I am trying to generate a space for dialogue, debate, and reflection to invite questions about things that we have very naturalised.

I find we know little about women working in construction, even though is becoming more common or perhaps accepted in society, is this something that you have been working on for long?

I started this project in 2016 and still ongoing, but women in Bolivia have been working in construction since the Chaco War in the 1930s. In most Latin-American countries brickwork has traditionally been seen as a male occupation. For the past years during Evo Morales presidential period, Bolivia has undergone a growing demand in the real estate business, with the subsequent need for manual labour as construction workers.

Even though construction is a trade of high physical demand that offers no respite, self-recognized Aymara, Quechua, and Bolivian women have found their way into this field, which have increasingly involved in the construction industry. Now they are more than 21,000 women working in construction, representing 4.5% of Bolivian employees who work in construction.

The job carries a world of discrimination. Despite this, the daily salary for brickwork scores above the minimum wage; representing a gainful opportunity in relation to other jobs like; informal commerce or cleaning jobs. There is no place for resting nor showing your weaknesses. Most of them see themselves, every day, performing the role of mother, father, and mason. Women builders perform all types of activities: shovelling, removing debris, preparing cement, cleaning ditches and carrying materials. They range from assistants to masters. They carry out different trades: masons, plumbers, gas workers, painters. Many of them find in the trade a passion. The age range of women builders goes from 17 to 66 years. Despite the hardship on the body, these ladies do not give up. Here I share a part of the testimony of Maria del Carmen, she works in the local government emergency unit in La Paz:

“Will is the only thing you need for this job. When you start, you can only handle small stones, and, with time, you will be able to handle big ones. Every day you become stronger. Woman builders are for me the strongest because they not only have to resist physical effort but also, they have to stand up against discrimination. In this job you grow old”. Words by Maria del Carmen

Do you see yourself continuing on this project in other cities of Latin America?

If I receive the invitation, I would not refuse it at all. I know there are women working in construction in Mexico too. But at the moment the questions I have are specifically related to the people, the territory and the history of the city of La Paz and El Alto, Bolivia. Coming from abroad, entering work in Bolivia implies starting to know and understand other logics different from those of my territory.

The project has taken me to wonder about the ancient conception of building in the Andes and how “modernity” has an impact too. This project also led me to wonder about the concept of inhabiting. Now I become an observer of the mixture and juxtaposition of gestures of building.

Do you think these women have inspired your own practice in any level?

This project, on the one hand, constantly confronts me with the complexity of the social and the responsibility of generating a representation of another social group or culture. That motivated me to start anthropology and documentary film studies that I am currently carrying out. In this way it inspired me, challenges invite me to question my own practices. Today, I am wondering about the history of the tools I work with, both; photography and anthropology. Now I am in the fourth year of the degree and this project is becoming my bachelor thesis. It has given me the opportunity to learn in the practice, and in addition work with long-term projects that gives the time to aboard this complexity.

Did you find any similarity between the challenges of photography and the work they face?

Yes, both of them are hard work. Most of the discrimination women builders faced can be mirrored to the challenge’s photography faces. It is sad and discouraging when your skills are questioned in relation to your gender. Discrimination furthermore is more complex than just gender, it is intersectional, crossed by notions of race, ethnicity, class, among others.

Any person's skills do not have to do with individual abilities, but especially with the learning and development spaces for those skills to emerge. I believe if one asks questions about how they develop their skills, behind there is always a good teacher, or work experiences that have been challenging them and making them grow as a professional.

Intersectional discrimination that denies entry into work spaces, limits access to knowledge and learning environments will block any capacity to develop the potential of the workforce of in this case women. The capacities and skills to carry out a job do not depend on gender, but on the generative potential of the development system that allows the incorporation of learning experiences to different people from more job opportunities, grants, fellowships. For example, this grant give visibility to my project. In photography, things are slowly changing, and editors are trying to hire or give more possibilities to women. Similarly, active networks of mutual support are being built between women who are setting up the majority spaces for men.

-------------

Sofía Bensadon is an Argentine photographer and anthropology student currently based in Buenos Aires, Argetina. Sofia’s work focuses on social stories occurring in her nation and neighbouring countries; Chile and Bolivia. Her work has been exhibited in Peru, Colombia and Argentina. Follow her on Instagram.

Verónica Sanchis Bencomo is a Venezuelan photographer and curator based in Hong Kong. In 2014, she founded Foto Féminas, a platform that promotes the works of female Latin American and Caribbean photographers. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

-------------

This article is part of In Focus: Latin American Female Photographers, a monthly series curated by Verónica Sanchis Bencomo focusing on the works of female visual storytellers working and living in Latin America.