Agathe Kalfas & Mathias Benguigui Offering A Different Face to the Refugees Crisis

-

Published22 Sep 2022

-

Author

On show this year at PhMuseum Days 2022, the four-hander collaboration Asphodel Songs attempts to provide a fresh viewpoint to a heavily represented place and issue—the one of migration on the island of Lesbos.

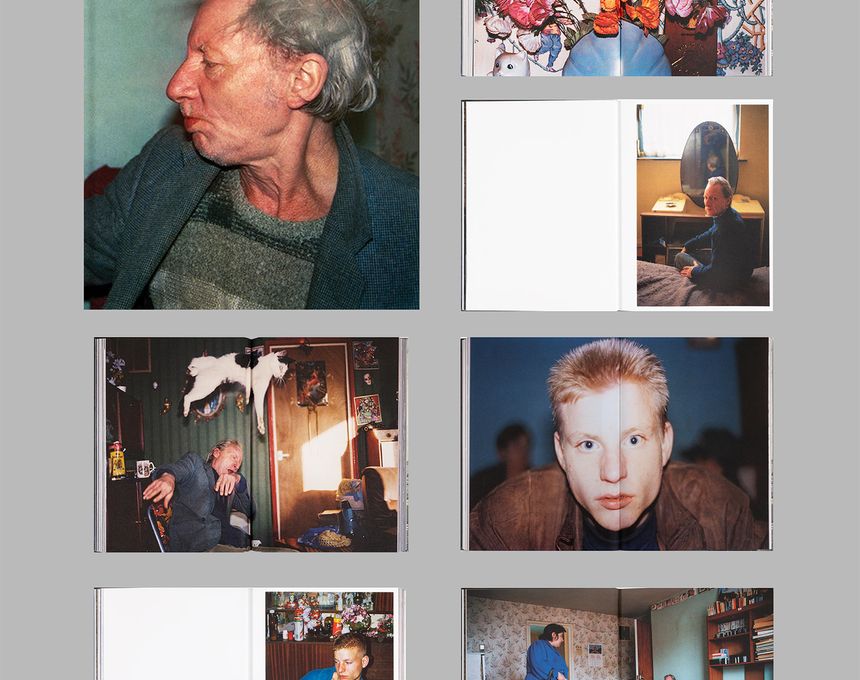

What should a refugee look like? As a person caught in a foul paradox, between oppression and freedom, robbed of their possession and their pride? Tired, frantic, damp, arriving at last on a boat too small, sorrow in their bones? Could they, on the other hand, stand in front of a camera with dignity and poise, flowers around their head? How do you portray a refugee? Who is a refugee? What does it mean to be a refugee? Asphodel Songs, a choral work by photographer and photo editor Mathias Benguigui and photography consultant and artistic producer Agathe Kalfas, addresses some of these themes.

Compelled to tell a different story—or, better yet, the same story in a different way—the project began as a creative collaboration between the two, quickly evolving into a lyrical work that reveals the many traits of immigration—various as the faces of people who took the perilous journey, their stories, their struggles—and everything in between.

“We felt a big hole in the iconography of the island,” Kalfas and Benguigui say, as images from Lesbos, the third-largest Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea, right off the coast of Turkiye, all told the same tale. When Benguigui was a photo editor, most of the photographs from wired photographers on the ground echoed the same message—a flat vision of the island, portraying the same face of the immigration crisis: Refugees arriving on packed boats, migrants deep in water trying to reach the coast, weary individuals on a beach, and people waiting in line to collect their food at a refugee camp. That's when Benguigui decided to try something new, teaming up with Kalfas, who is half French and half Greek and felt compelled to create a tale that resonated with her background.

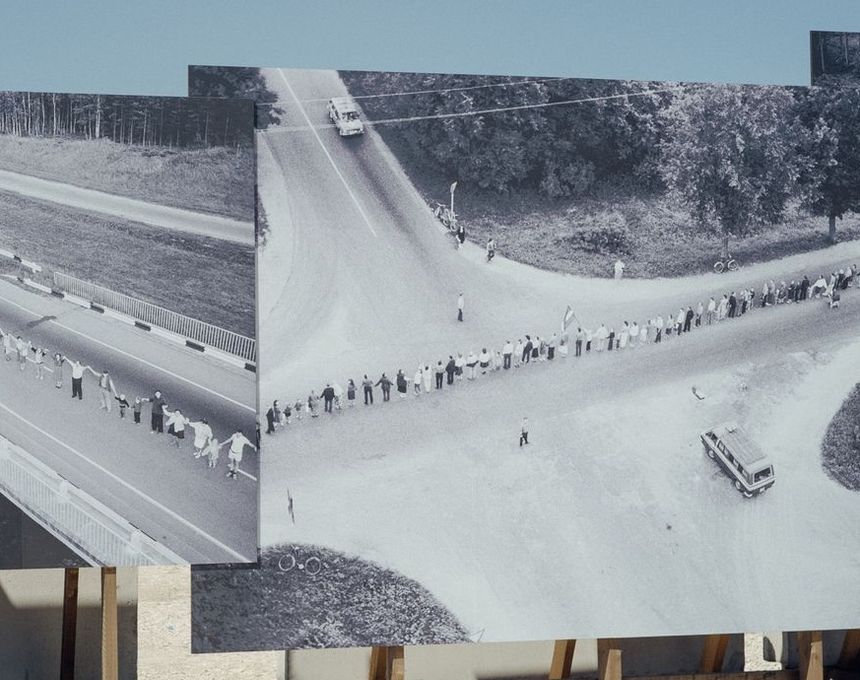

They proceeded deeper into the historical method, investigating mythology, the first stratum of local culture, and the ancient waves of immigration that history creates. They began by documenting the landscape, typically overlooked in mainstream photography: Lesbos is Greece's third largest island, however, images in the media only cover roughly 10 percent of its total territory. They discovered signs of the past in the landscape. The Ottoman empire controlled the island for four centuries; it's not uncommon to witness antique minarets or etched Arabic letters in a typical Orthodox community. They identified several layers—iconography, history, sociology—as well as the remarkable position Lesbos symbolizes as a bridge between east and west, as well as for the civilizations that passed through the island.

A feeling of “collective memory” pervades the island, held by both those who arrived long ago and those who do today. “There is a huge collective memory about migration that you can feel in every stones, in every person, in every tradition; it's [as if] the past is alive all the time. It's all the different strata of histories living all together,” Benguigui and Kalfas explain.

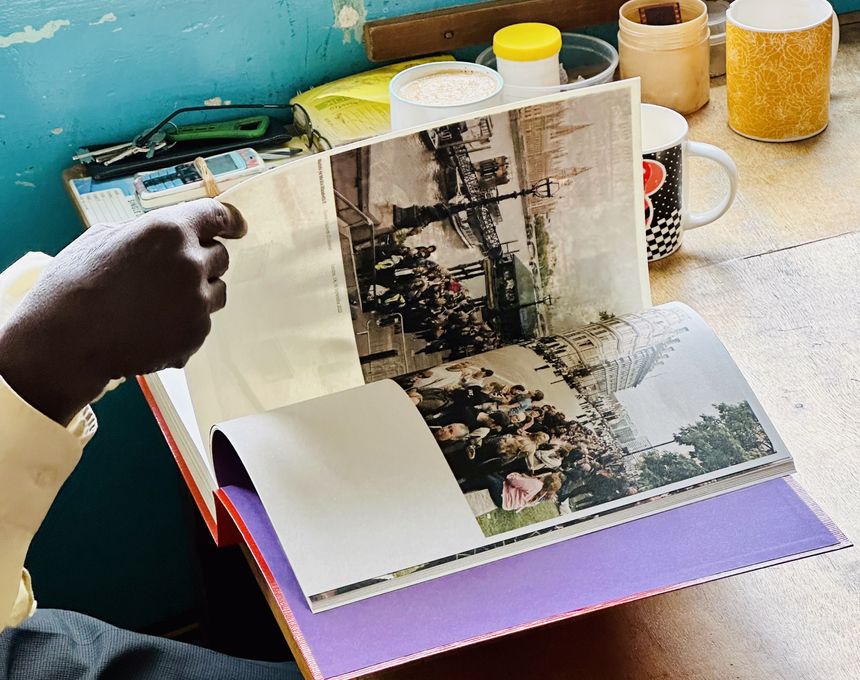

Along with landscape photography, they made portraits “in collaboration” with the inhabitants on the island, with no backdrop to make it unclear if the subject is a freshly arrived refugee or a Greek descendant of immigrants. They place everyone on the same level, with no preconceptions or disparities, avoiding clichéd depiction through acquired stereotypes. They were successful in their goal. During a photo exhibit, people asked why they hadn't photographed any refugees, given the subject and location: “‘You are talking about an island with refugees, you are talking about a migration crisis, [yet] there is no refugee in your pictures,’” several observed. There were plenty of migrants in the photos; they just didn't match our internalized predictions.

Through evocative images, they inspire the spectator to project something beyond what is obvious. Three young males are seen partially submerged in the sea in one photograph. It's unclear if they're bathing or drowning, victims of a sad fate as they worked strenuously to build a brighter future for themselves. Intuitively, we know that what has been revealed is not exactly what it is. “All the pictures show tragic things, but you don't see that it's tragic,” say Benguigui.

With this approach, the audience takes on the role of engaged actor, reappropriating and reinterpreting the images. In this scenario, the photograph becomes a metaphor for something broader, and the cloudy fate of migrants comes to the forefront: “You don't know if you [get] inside Europe, if it would be worse or not,” Benguigui argues. The image itself contains this question, the uncertainty between them playing and drowning. Asphodel Songs also employs subtle symbolism, exposing the truths and challenges behind the photographs only afterwards and through captions.

Aware of the subjectivity of their work, Kalfas and Benguigui are open to a range of viewpoints. “It's the cohabitation of all those points of view that could touch the audience differently.” They aim to engage individuals who are weary of seeing the same photos, who “don't want to look at it again, and they don't want to question themselves about what it means to be a refugee?” It is a contemporary malaise resulting from the present overload of information, in terms of format, medium, and content. “Democracy is also about diversity of point of view. So this work touches the intimacy, but also the politics,” Kalfas says.

Finally, the initiative wishes to respect and honor the Greek population. The migration problem is a tragedy for refugees, but it also has an influence on the local community, their self-image, how it is depicted in the media—a "prison" for foreigners living in deplorable conditions. Many Greeks feel disconnected from their territory. The massive economic crisis, exacerbated by the epidemic and the fall of tourism, one of the main financial resources, intensifies the emergency and the disconnection.

Benguigui and Kalfas want the Greek population to be seen, beyond the imagery of immigration shown in mass media. The Moria camp, one of the most well-known refugee camps, gets its name from a nearby village, not the other way around. But while everyone is familiar with the camp, few are familiar with the village and its inhabitants. “It is important to put those complexity together, to work on the dignity of people.” They also aim to bring the project to the Greeks and the migrants on the island, in order to foster a genuine debate that takes place not just conceptually, but also in real life and with the protagonists. “We are all human and we are all people moving around,” Kalfas says. “We are all descendent of refugee. So why do we have to show those people in those types of situations to be sure that they are refugees?”

All photos © Mathias Benguigui and Agathe Kalfas, from the series Asphodel Songs

--------------

Mathias Benguigui is a French photographer focusing on long-term personal documentary projects, questioning memory, identity and uprooting.

Agathe Kalfas is a French photography consultant and artistic producer. Find their project, Asphodel Songs, here.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Twitter.

--------------

This article is part of the series New Generation, a monthly column written by Lucia De Stefani, focusing on the most interesting emerging talents in our community.