A Paradise Lost: The Dark History of Pitcairn Island

-

Published4 Jul 2018

-

Author

Surrounded by hundreds of miles of open ocean and an exotic expectation, Rhiannon Adam set-off to Pitcairn Island in the south Pacific to unveil the true realities of life in paradise.

Surrounded by hundreds of miles of open ocean and an exotic expectation, Rhiannon Adam set-off to Pitcairn Island in the south Pacific to unveil the true realities of life in paradise.

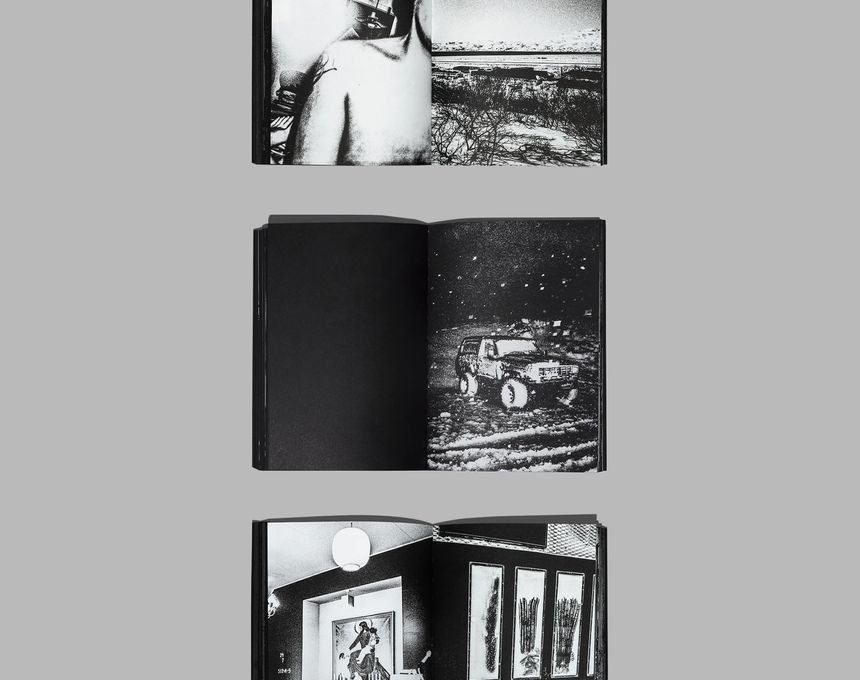

Pitcairn just a small two miles long and one-mile wide island found in the vastness of the Pacific Ocean. In here, lays an almost mythical and remote landmass, which is only accessible by a quarterly supply vessel. Once you set foot on the Anglo-Tahitian idyll island there is no scape until the ship returns. Big Fence, A Portrait of Pitcairn Island - is a close picture about an island that calls for paradise but unveils a community’s obscure truths.

Rhiannon Adam, ventured to the island in order to document this minute community, which today is only made of just one child and 42 islanders. A tense and claustrophobic sense is perceived throughout Adam’s uncanny single portraits, all juxtaposed by a sense of exotic tale, Polaroid immediacy, as well as, found photographs and objects.

Can you talk about how you reached Pitcairn Island? What was that journey like? How did you first hear about the island?

Pitcairn Island may be a minute blip in the middle of the vast Pacific Ocean, but in certain circles it is quite well-known. In my case, I came to know about the island as a child – my parents gave me a copy of the famous book, Mutiny on the Bounty.

At the time, we were embarking on a journey on a boat of our own, with the aim of sailing around the world – just my mum, dad, and I. I was a voracious reader, and our boat was very back to basics. There wasn’t enough daily electricity to run a tv/video player, so I read. A lot. When we first left on the boat, and in fact, through to the end of our journey, I wasn’t happy – I hadn’t wanted to leave my home in Ireland, or my friends. When you’re a kid in that situation, it isn’t freedom, it’s a prison. So, I would escape into the pages of books. When we were sailing, we didn’t have any money, so we didn’t have the funds to dedicate to photography or chronicling our journey... I have so few images from that period – instead, I’d collect souvenirs. Things that had a memory for me. It was an eclectic mix.

To get to the island, you have to book on one of these quarterly rotations and get yourself to Mangareva – the furthermost point in French Polynesia that you can fly to, a tiny island in the Gambier group. The boat trip from Mangareva is a couple of days at sea, but when it leaves you on Pitcairn, you’re stuck for the next three months until the boat returns. Watching it motor away is gut wrenching. On my way back, I elected to take the long trip back to the supply ship’s home port, Tauranga, in New Zealand. That took 17 days at sea, and at times it was pretty rough.

Your initial motivation for starting this project was based on the notion of the "utopian" image of how one imagines an island in the Pacific: paradisiacal or nightmarish. How do you find your initial idea evolved as you worked on your project?

Well, I didn’t have a completely set idea of how the project would evolve, but initially I had not planned to focus on the negative, nightmarish attributes. Those aspects just became more and more difficult to ignore as time went on. I knew it wouldn’t be a real Utopia – I don’t think that place exists… it’s like religion, sometimes we need to believe in something to make the rest of life bearable… for many that’s the idea of Utopia. I’m a realist, and I don’t believe in any god – I also don’t believe that Utopia exists. Yet, I find the concept of it fascinating. I can’t photograph ‘heaven’ but I could travel to a place that many believe is Utopia – a place that determined its own code for life in reaction and rejection of the outside world. In reality though, it is more like Alcatraz.

Initially, I aimed to photograph every islander to create a lasting record of this bizarre place, or at least that would be my starting point. I knew that the island had a dark history – not just the mutiny and that criminal past, but more recently. There had been an extensive investigation into a long legacy of child abuse. In 2004, several Pitcairn men went on trial – and in total eight men were convicted. One of these is the current mayor, Shawn Christian, and one is his father, the former mayor Steve Christian. So, I suppose I knew that it wouldn’t be easy to meet my goal. Of course, with the history, the islanders are very suspicious of outsiders, and particularly anyone seen as a journalist. I lived with Steve Christian and his wife Olive (for whom I felt very fond) for much of my time on island – I was conflicted. On the one hand Steve was convicted of awful things, but here he was being charming and charismatic.

In the end the project became partly about the island, and partly about my story and experience of it. The images all feel very personal to me, even though on the surface many may seem like straight portraits. I think that the way that I was treated allowed me to retreat into myself more – the project was a daily struggle, even motivating myself to go outside, smile and try to engage with the islanders became a struggle.

You mentioned the challenges of gaining access to locals due to being an outsider. However, you did manage to photograph several locals in what seem to represent their private/intimate spaces. How did you manage to break the barrier of trust?

It was extremely difficult. I don’t think that I ever gained their trust, but I think they got used to me being around. Some people I never won over and are not included at all… but I think in the end, most islanders are in some way represented in the wider project, if not always in portrait terms. The project evolved in any case, and it became less important to photograph each and every person, some are represented by objects or things that they have made, and some I photographed but I didn’t feel that their image necessarily added to the narrative and I have cut them out.

But I am very persistent – in some cases it took months to win subjects over, and with most I had just one chance to photograph them. Shawn’s portrait for instance, was taken on my very last day. Of course, the only accommodation on the island is home-stay – I was living in islanders’ homes. I had access to their lives, and I lived within both of the key family groups on the island. We would eat together, and chat, but it was hard to cross between that familial context and into my role as photographer.

Getting them to give up their time for me took a lot of persuasion… and not just that, many didn’t want to associate with me over fears for what that meant, and worries over my motive, and concerns of how they would be perceived by their fellow islanders. I was also definitely on the back foot – they had very bad experiences of solo female journalists in the past and put me in the same bracket – that I would publish negative stories from the island. Sadly, it became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Though I made some friends, and had moments of joy, the island as a whole certainly left a bitter taste in my mouth – I wonder if it will be able to carry on for too much longer. The Pitcairners don’t want you to say anything negative at all, but for me, truth is more important.

© Rhiannon Adam, from the series Big Fence, A Portrait of Pitcairn Island

The photographs capture a sense of claustrophobia - was this a conscious act while you were there? Can you elaborate?

Pitcairn is not just an island – it is an inaccessible island with a difficult history and a tiny population – when you add that it used to be the legendary home of the infamous Bounty mutineers, it is a heady mixture. Islanders didn’t really want to be seen to openly associate with me and those that did sit for me wanted to be photographed in private, one on one – I suppose this was in case they 'got it wrong', and that I was a 'snake in the grass' as I’ve since been called.

Every story comes back on itself, everyone is interlinked, every seemingly simple problem becomes boggy and elaborate. It’s impossible to separate fact from fiction, truth from lie. If I could say that the project was ‘about’ anything – it is probably ‘about’ claustrophobia and the implications of interdependence. Of course, many wonder about the validity of the trials – did the offences really take place? Or, if it was so widespread, why didn’t the women and girls report anything sooner? Why are families unsupportive of those who spoke out? Why did the wider community support the men? When your off island, these questions seem obvious ones to ask, but when you are there, it is crystal clear – there is almost a hive mind on Pitcairn – individualism is abstract. If you give evidence against an island man, the chances are they are a relation of yours, in fact if you look at the family tree, almost everyone is related to one another through multiple generational links.

Physically the island is impenetrable too – steep sided and rocky. There are no beaches, apart from a tiny strip of sand at the foot of a perilous cliff, only accessible by a high-risk descent. If you do decide that the risk is worthwhile, the sand is like a mirage – perfect from far away, but up close you realise that the water is filled with rocks and it’s impossible to swim in.

---------------

Rhiannon Adam was born in Cork, Ireland and currently lives and works in London. Her work is primarily concerned with myth, nostalgia and the passage of time. She regularly undertakes long-form projects, going wherever the work takes her. Follow her on PHmuseum, Twitter and Instagram.

Verónica Sanchis Bencomo is a Venezuelan photographer and curator based in Hong Kong. In 2014, she founded Foto Féminas, a platform that promotes the works of female Latin American and Caribbean photographers. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.