Resolution 808

-

Dates2017 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location The Hague, Netherlands

Resolution 808

inside the Yugoslavia tribunal

During the nineties, the world was shocked by the war that was raging over the Balkans. Europe’s deadliest conflict since World War II was marked by grim war crimes, including genocide, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing. The conflict lasted for almost ten years, left over 130,000 people dead, and led to the breakup of Yugoslavia.

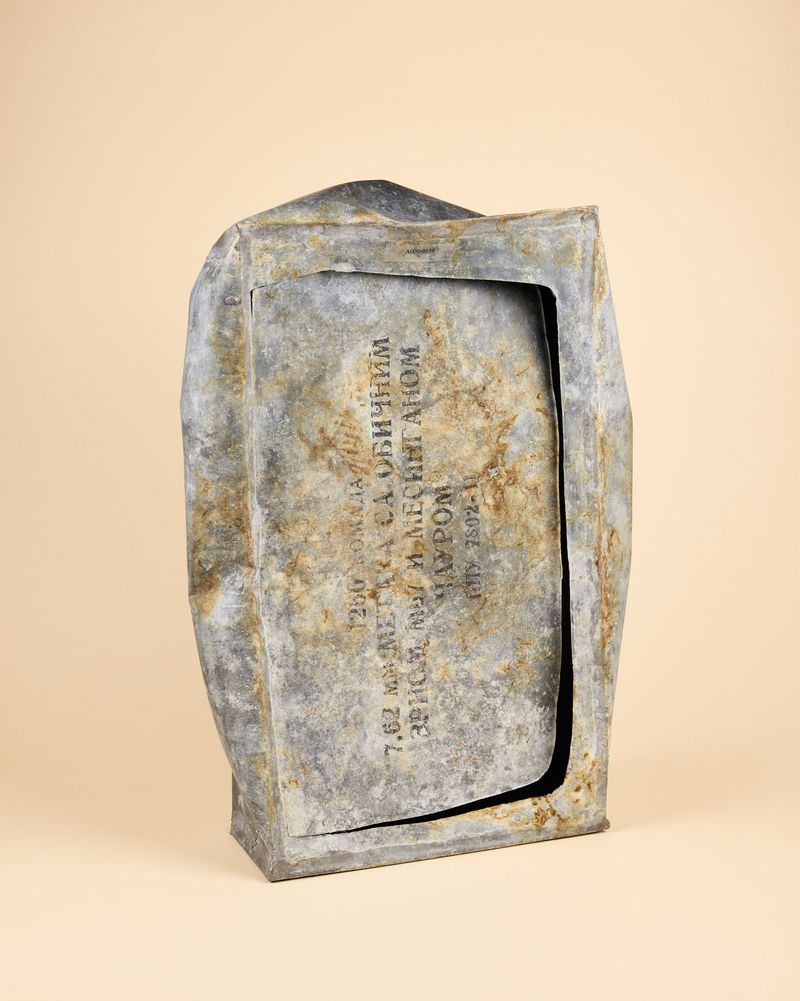

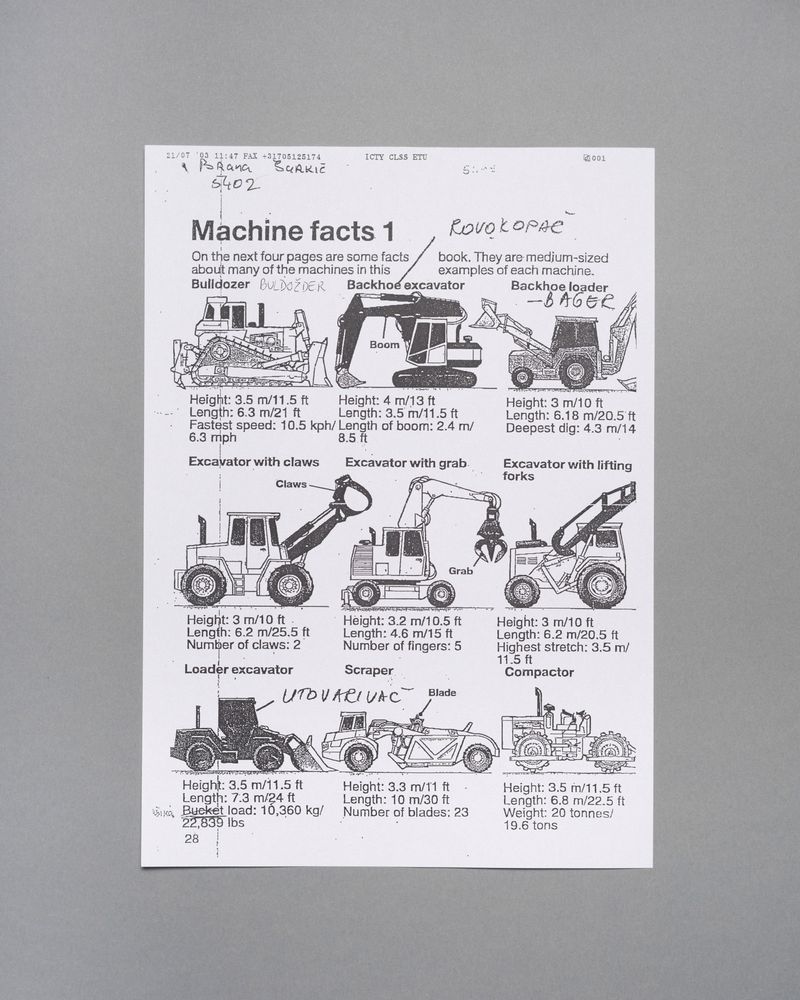

On February 22, 1993, in the midst of the atrocities, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 808 to establish the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). For the first time since the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials, a war crimes court was set up to prosecute the political and military leaders that orchestrated the war. While investigators started to collect evidence in the Balkans and prosecutors started to compose indictments in The Hague (the Netherlands), the hunt for the war criminals started. Ultimately, it took 24 years and over 10,800 trial days to bring the 161 indictees to justice.

In the final year before its closure, we entered behind the scenes of this international institution. We set out to tell the inside stories of the people that pioneered international criminal justice. Also, we wanted to document the places and objects that were essential to the trials, but remained closed to the public at large.

The grant will allow us to produce the second part of the project: we will investigate the impact of the work done by this tribunal in the Balkans, and how the memories of the conflict are built, perceived, transmitted and manipulated today in the region.

Interpreting war crimes (text by Jorie Horstuis, journalist)

‘Sometimes, I have to say nasty words that I would normally never use. Or I have to insult the judge, or the prosecutor. In the beginning, that was really awkward. I had to learn to distance myself from my speech, to become a mechanism. That is the only way it works.’

Martina Fryda-Kaurimsky works as interpreter at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Early 1995, she was asked by the office of the prosecutor to come and work as an interpreter in Bosnia, where war was still raging. For the first time in history, a tribunal was set up in the middle of a war to prosecute and judge the leading parties and their criminal acts. There was little or no precedent to guide the practical work of this institution, the first international war crimes court since the post-Second World War Nuremberg and Tokyo trials. After a couple of years in the field, Martina was sent to the ICTY, where she still works today. ‘When I came in 1999, everyone was thrilled: the first perpetrators of the war were finally sent to justice, after years of investigations. For me, it was a completely new way of working. Instead of interpreting the meaning of a statement, I had to interpret it word by word. In court, we had to stick to the original texts, even if we found them not important, or even inappropriate. The pressure was high: if I would misinterpret a sentence, the blame would immediately be put on me by the prosecutor or the defense. It was very unnerving.’

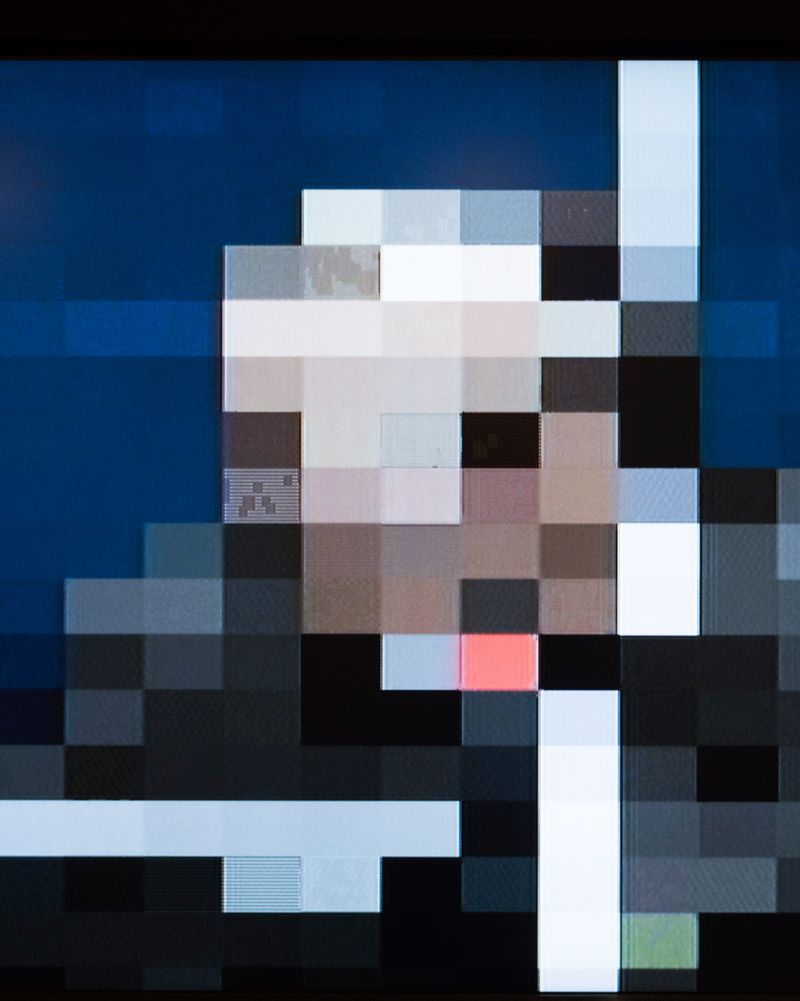

Interpreters like her tend to be invisible. If no one notices them, they are doing a great job. But in the meantime, their presence is of uttermost importance: judges, prosecutors, defense lawyers, accused and witnesses come from all over the world and speak different languages. The trials are all about words and their meaning, and without interpreters, the proceedings would not function.

'Interpreting requires an unnatural skill', explains interpreter Simonida Stosic. 'You have to speak and listen at the same time. Try it, and you will understand: it is a schizophrenic ability.' Simonida left the former Yugoslavia in 1992, at the beginning of the war. ‘I didn’t like what I was seeing. The leaders were about to destroy the country, and people easily fell for propaganda. If that’s the majority, I thought, my place is not here.'

She started working at the ICTY in 2000, and soon, she realized the gruesome stories she heard in court had a big impact on her live. 'The human power for evil leaves you speechless', she says. 'Everyone who is working here is a little damaged.' In the meantime, former leaders like Milosevic, Karadzic and Mladic used the trials as a new stage for their political speeches. 'For them, the courtroom is like a theatre. It requires a good act.' During the proceedings, Milosevic sometimes made friendly gestures to the booth and tried to get some sympathy. 'I simply ignored him', recounts Simonida. 'I will never forget what he did to our homeland.'

In December 2017 the tribunal has finally closed its doors: it has indicted 161 people, which is unprecedented in international criminal law. The interpreters in total have worked 80,000 days in the courtroom. 'Of course, I am proud of what we achieved', says Simonida. 'Even though there were some difficulties and mistakes on the way, I think the tribunal has done something good. If it wouldn't exist, these people might still have been in power.' Still, like most of her colleagues, she is reluctant to tell the people back home that she is working in The Hague. 'In Belgrade, they are very critical about the tribunal: they say it is a NATO puppet institution, and that there are only Serbs who are being prosecuted. They believe the tendentious allegations in the media. I prefer just not to talk about it.'