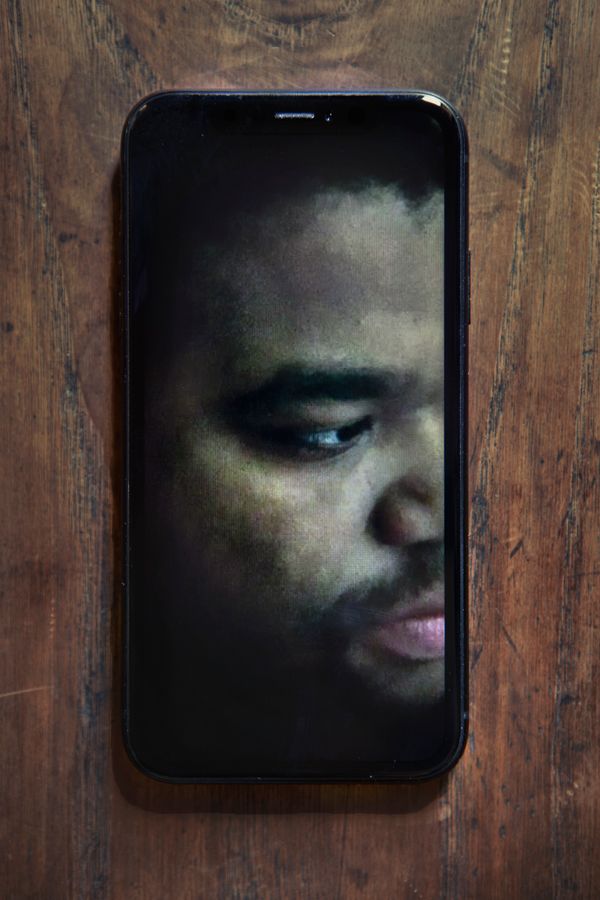

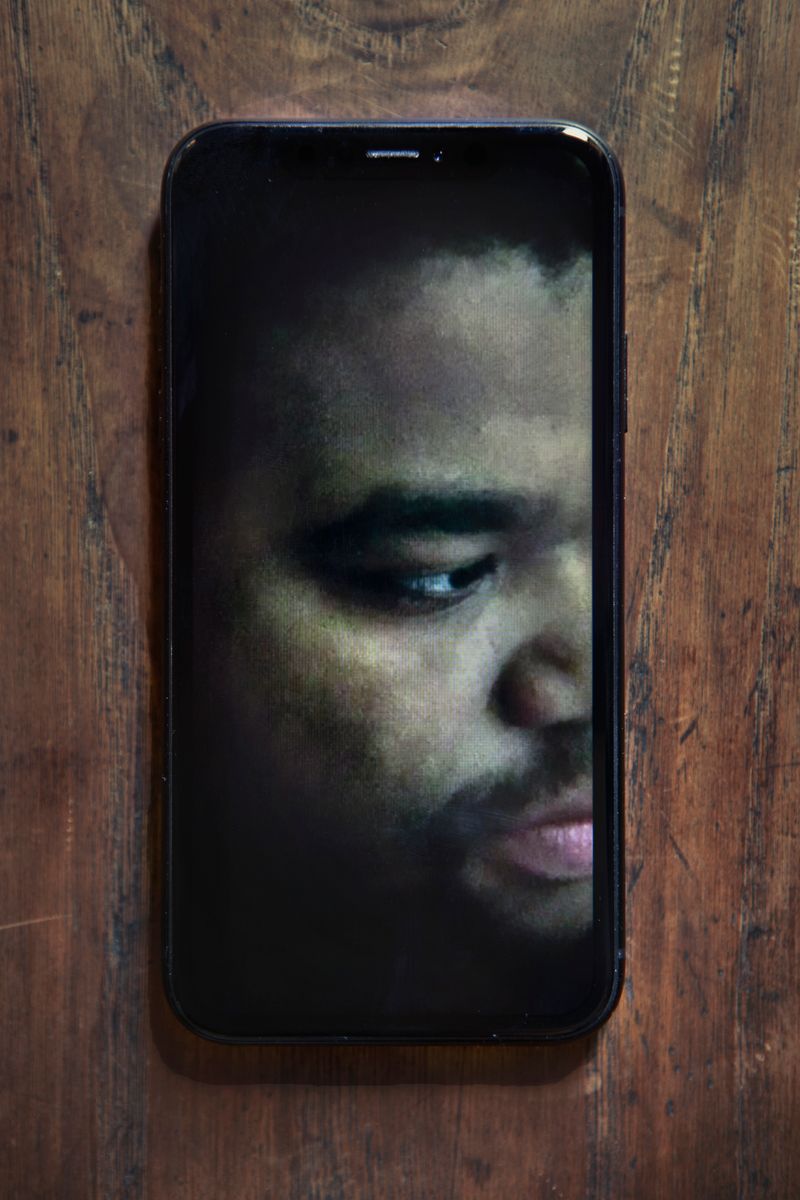

Marco Casula, 28, chemistry expert from Mestre, near Venice, Italy, stationed at the Ny-Alesund National Institute of Polar Research, Svalbard Archipelago, Norway The Svalbard Archipelago, around 1,000 kilometres from the North Pole, is the one of the northernmost inhabited places in the world. In summer, 200 people live here on the international research stations. This winter, the number dropped to around 30. It’s a key monitoring point for climate change, with researchers coming from Europe and Asia. And, due to its isolation, it’s one of the few truly COVID-19-free places in the world. People wear ski masks instead of medical masks, and gloves are used to protect against the cold, not the coronavirus. You can still shake hands, eat reindeer and have a beer together on a Saturday night. Marco arrived on January 1 to man the Italian research station and was supposed to return home in March, but nobody can replace him due to the virus crisis. “The coronavirus will decide the date of my return to Italy, and since none of my colleagues can come here at the moment, I’m staying. I also have a responsibility to carry on with my work and not interrupt (by leaving the station unattended) the climate data that Italy has been collecting in the Arctic for more than 10 years.” “Every day I take snow samples, measure the snow cover, the sea ice, maintain the instrumentation, collect data on this delicate environment, which is crucial in showing climate change. Here, you can see the effects of climate change in front of your eyes. … Last week, in the space of just a few hours, the temperature went from minus-30 to positive-2 degrees and it started raining. Rain at these latitudes is unheard of.” “I can go out and enjoy these unique and magnificent landscapes. I can have human contact with colleagues from the other international research stations. I have all the space I want. I think people who are forced to stay in their homes, not to mention those in quarantine or in hospital, have a much harder time. In this sense, I consider myself in a privileged position.” “When I left (to come here), my mother was very worried. She used to tell me to cover up. Now my thoughts are with them (my parents) and my friends.”