'Tsavt Tanem' — I take away your pain

-

Dates2018 - Ongoing

-

Author

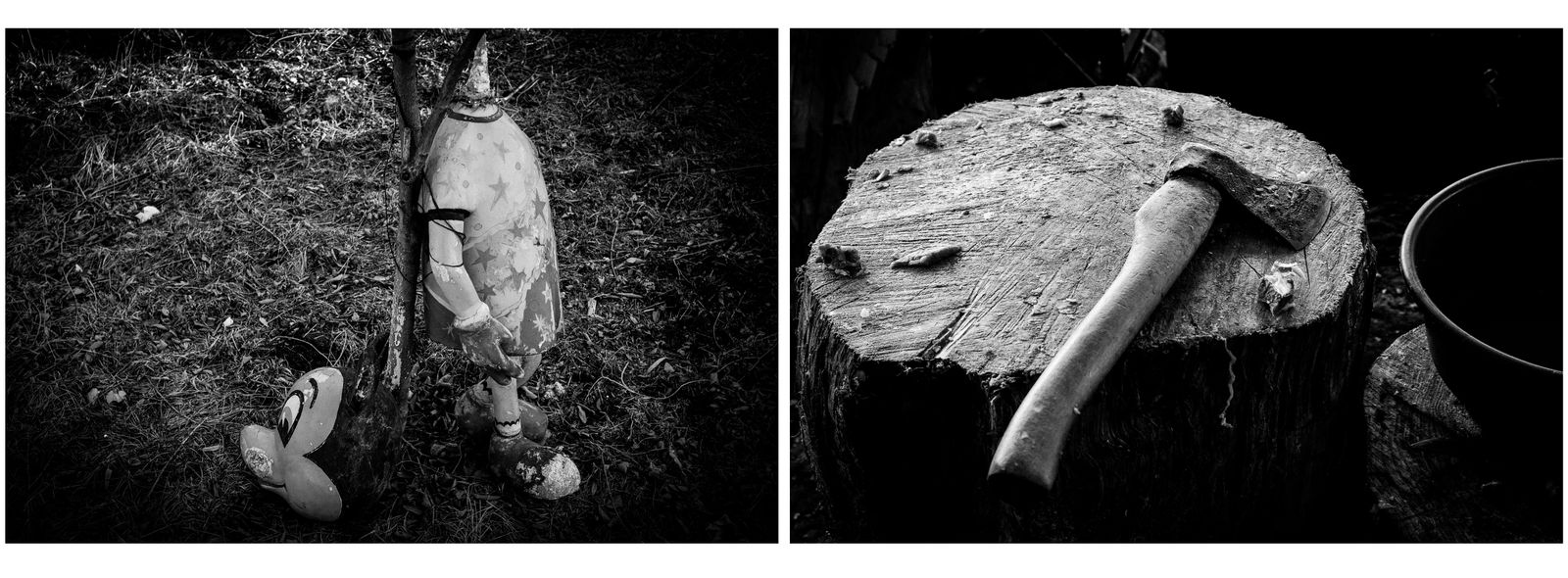

Armenia, the constant victim. At least this is how history seems to judge this tiny nation in the Caucasus, which has borne the brunt of many of the disasters — both geopolitical and natural — that have riven that region.

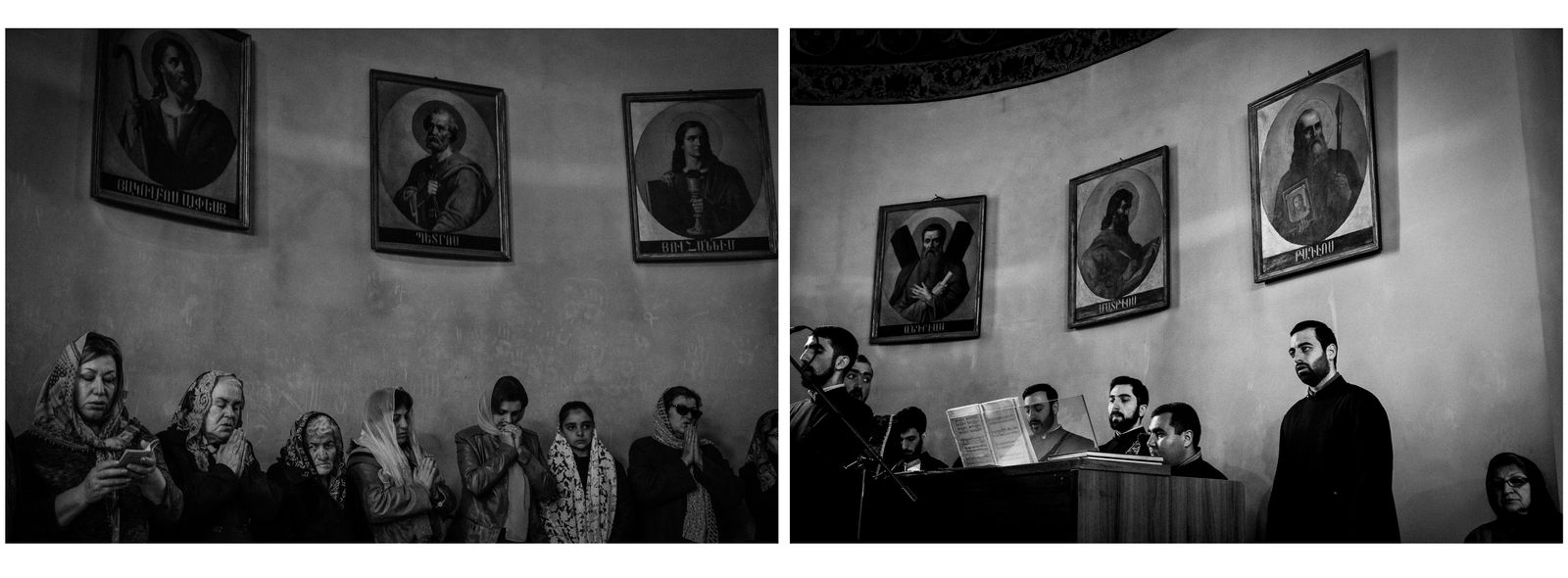

At times Armenian culture seems built on suffering, almost as if it thrives on it. A common term of endearment, ‘Tsavt tanem’, means ‘I take away your pain.’ The duduk, Armenia’s ubiquitous woodwind instrument, moans a doleful dirge that seems to echo centuries of struggle.

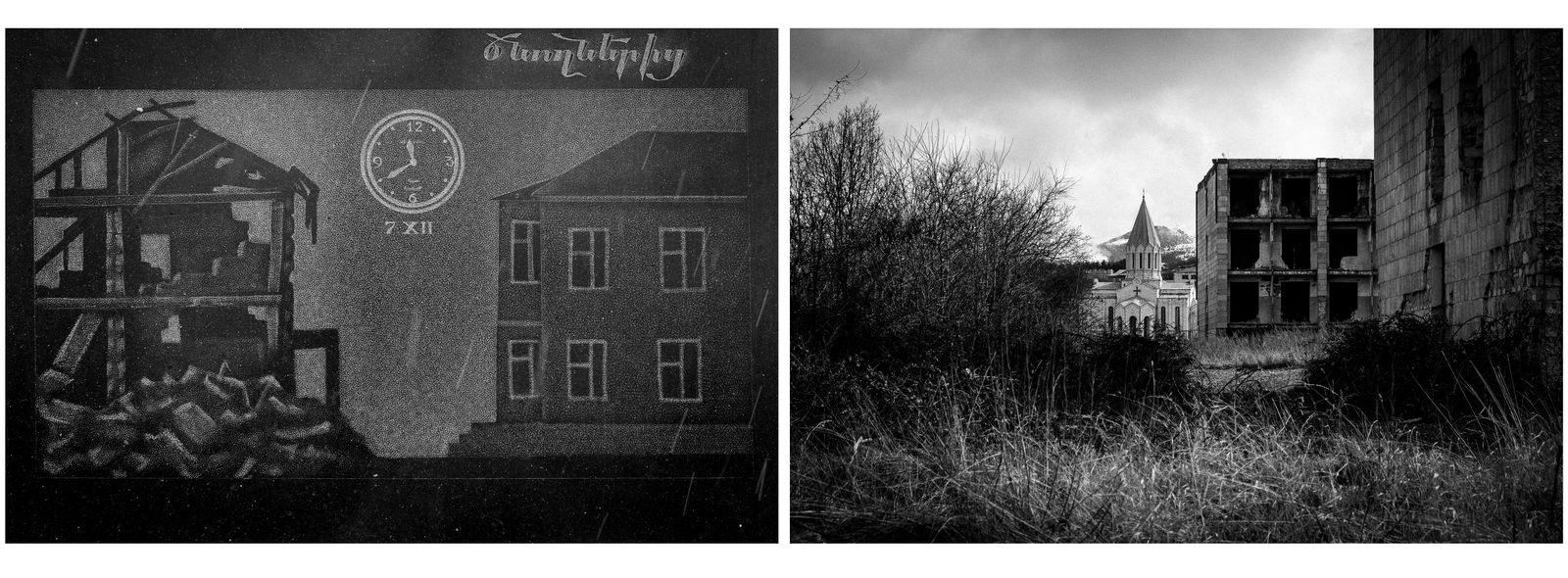

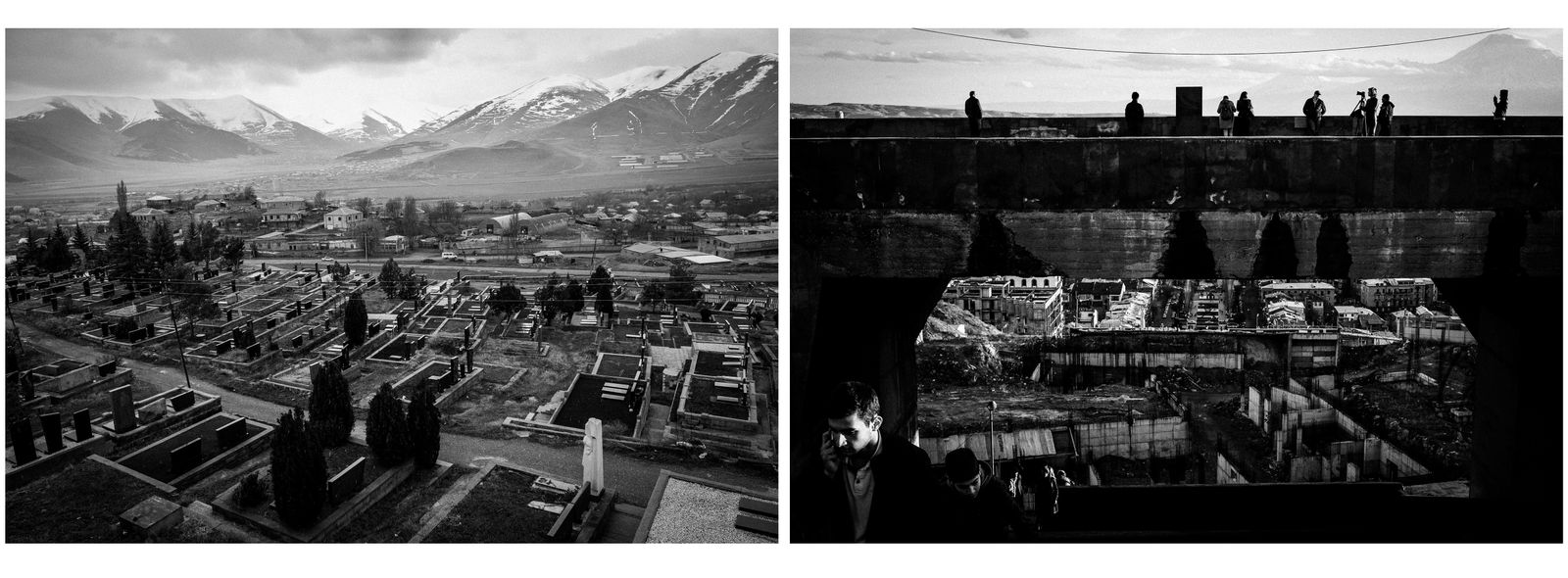

The last hundred years alone have seen conflicts with Turkey and the genocide of 1915, subjugation by the USSR and its eventual collapse, the loss of large swathes of territory (including the national symbol, Mount Ararat), the devastating earthquake of 1988 that killed tens of thousands, and the unresolved ‘frozen’ conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh with post-Soviet Azerbajian. This is a disproportionate level of turmoil for a nation of barely three million, but perhaps it is the price to be paid for its location on an historical crossroad and the fractures of a tectonic plate boundary.

Yet somehow it tenaciously survives, even as contemporary Armenia struggles with its domestic politics while also being squeezed between a strident Turkey in the west and an aggressive Azerbaijan in the east. Indeed, there is a sense that this devout land of countless churches is now far more willing than previously to assert itself.

This series seeks to take the viewer on a journey across an emerging Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh — burdened by history, forever caught betwixt and between. Surveying the tense borderlands with Turkey and Azerbaijan, the 1988 earthquake zone, and the Soviet legacy, the images meditate upon some of the touchstones of Armenia’s modern history, while questioning the future awaiting this geopolitically critical yet frequently overlooked nation. So often it has been shaken by forces beyond its control, but perhaps a future beckons in which it will no longer be the constant victim after all.

The grant would be used to continue and resolve the project.