The Lost Chapter: Nampula 1963

By Délio Jasse

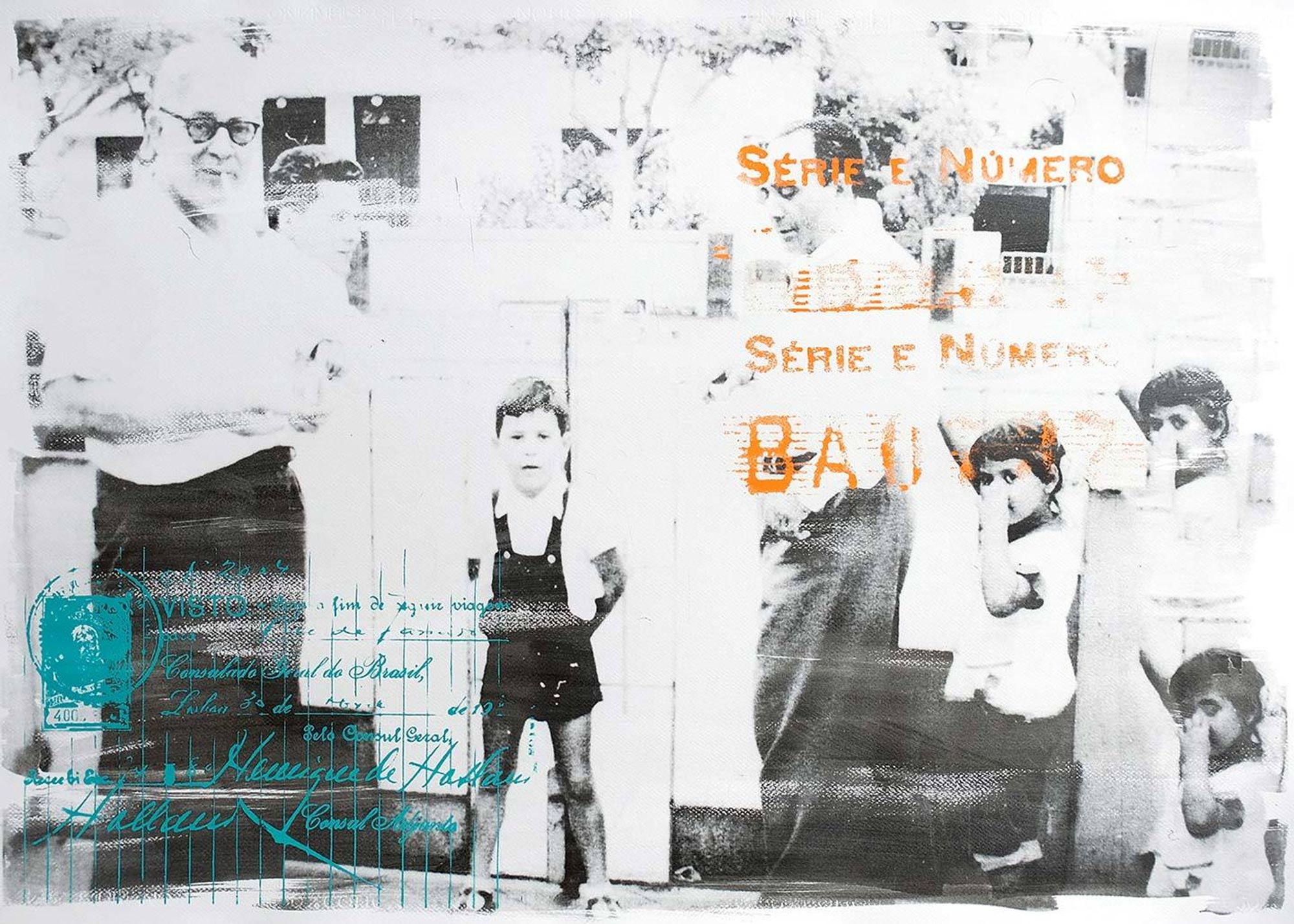

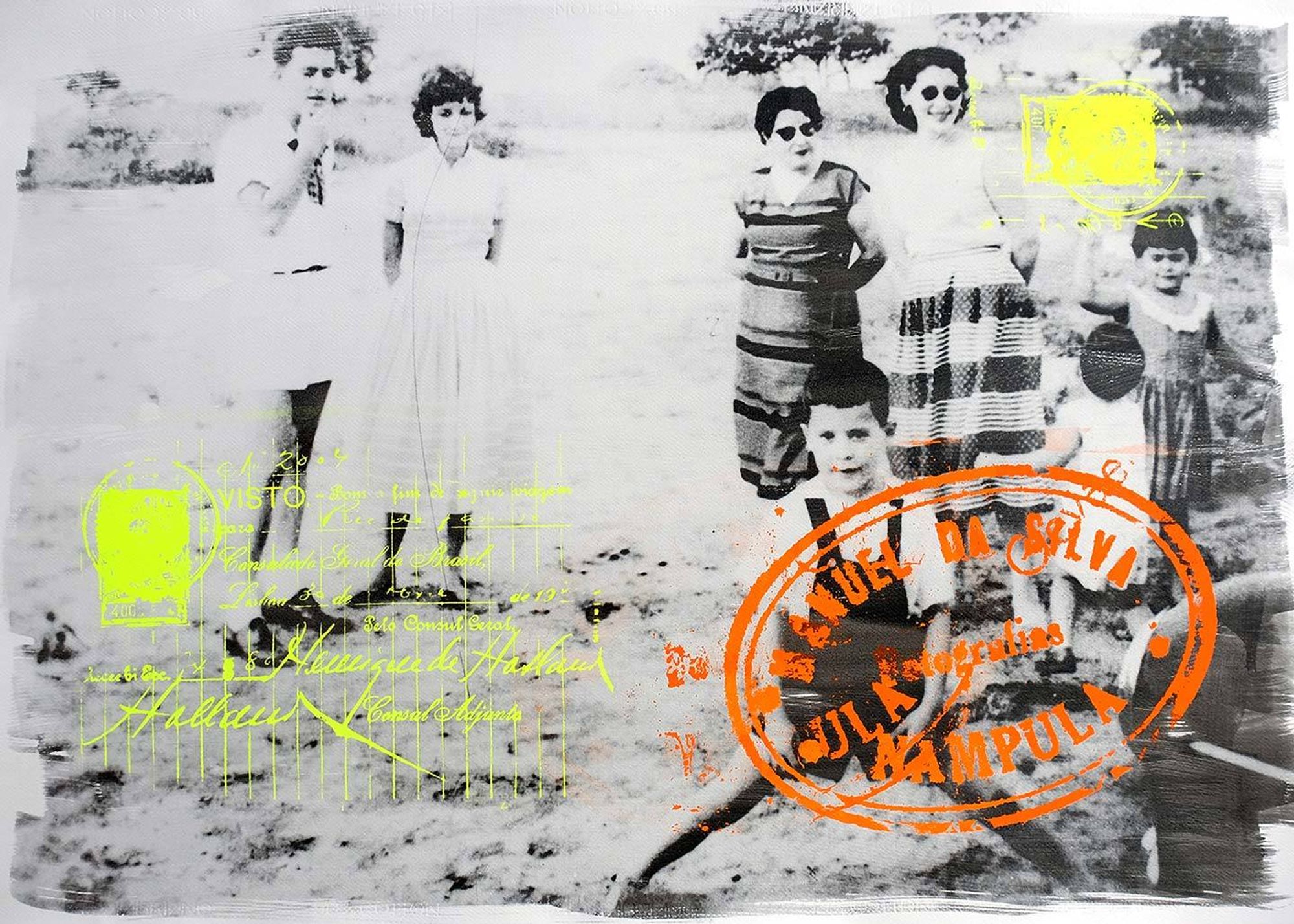

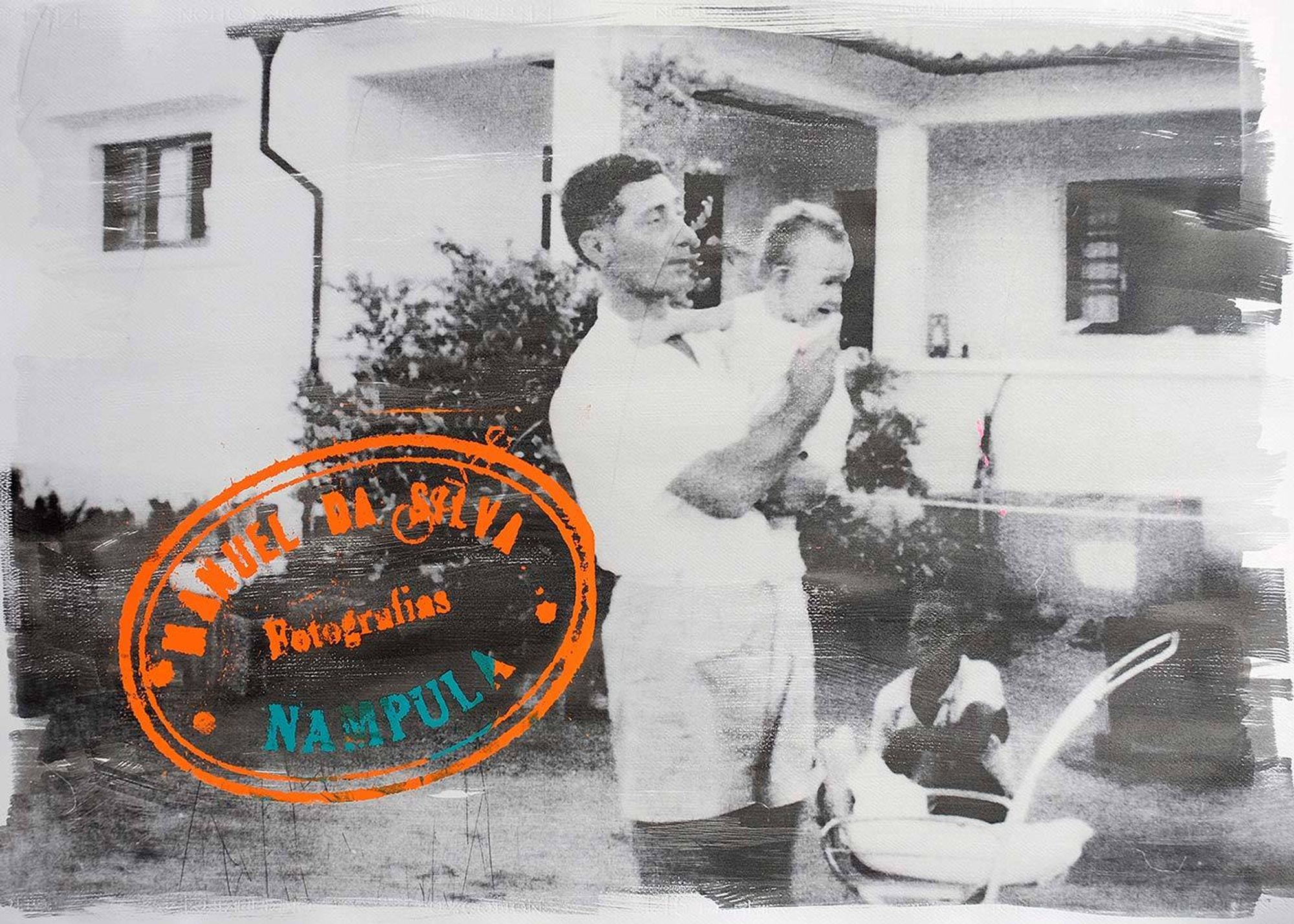

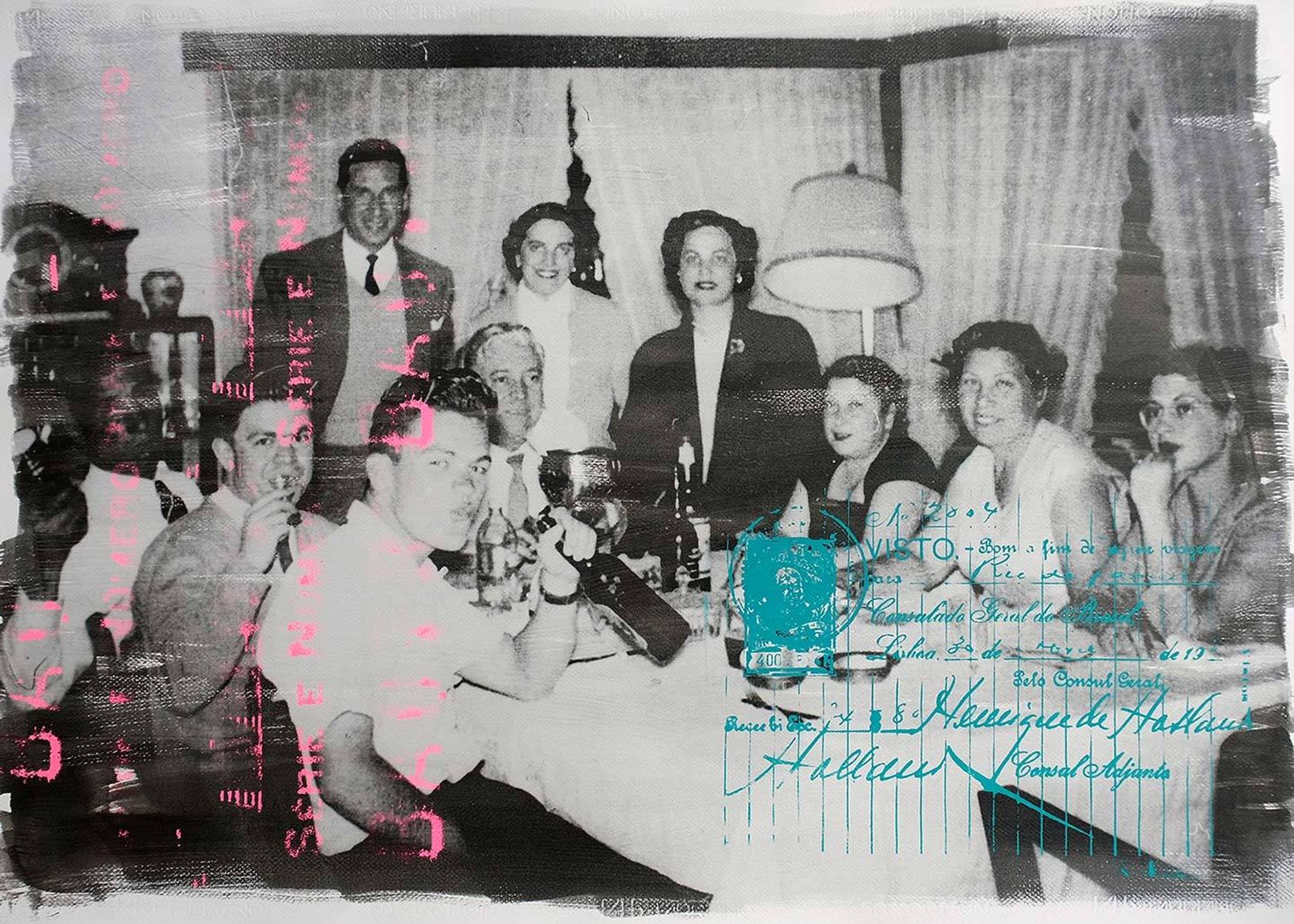

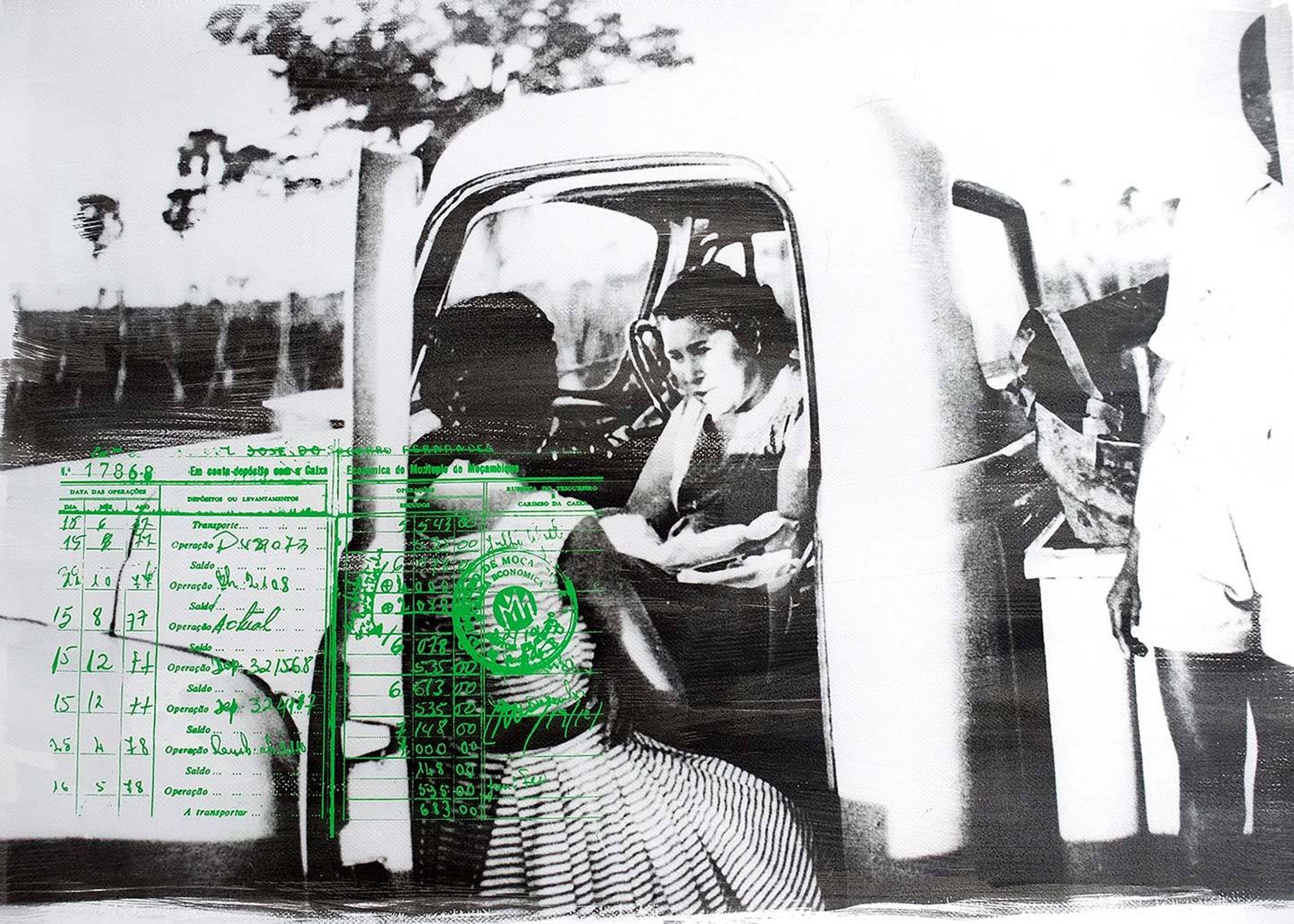

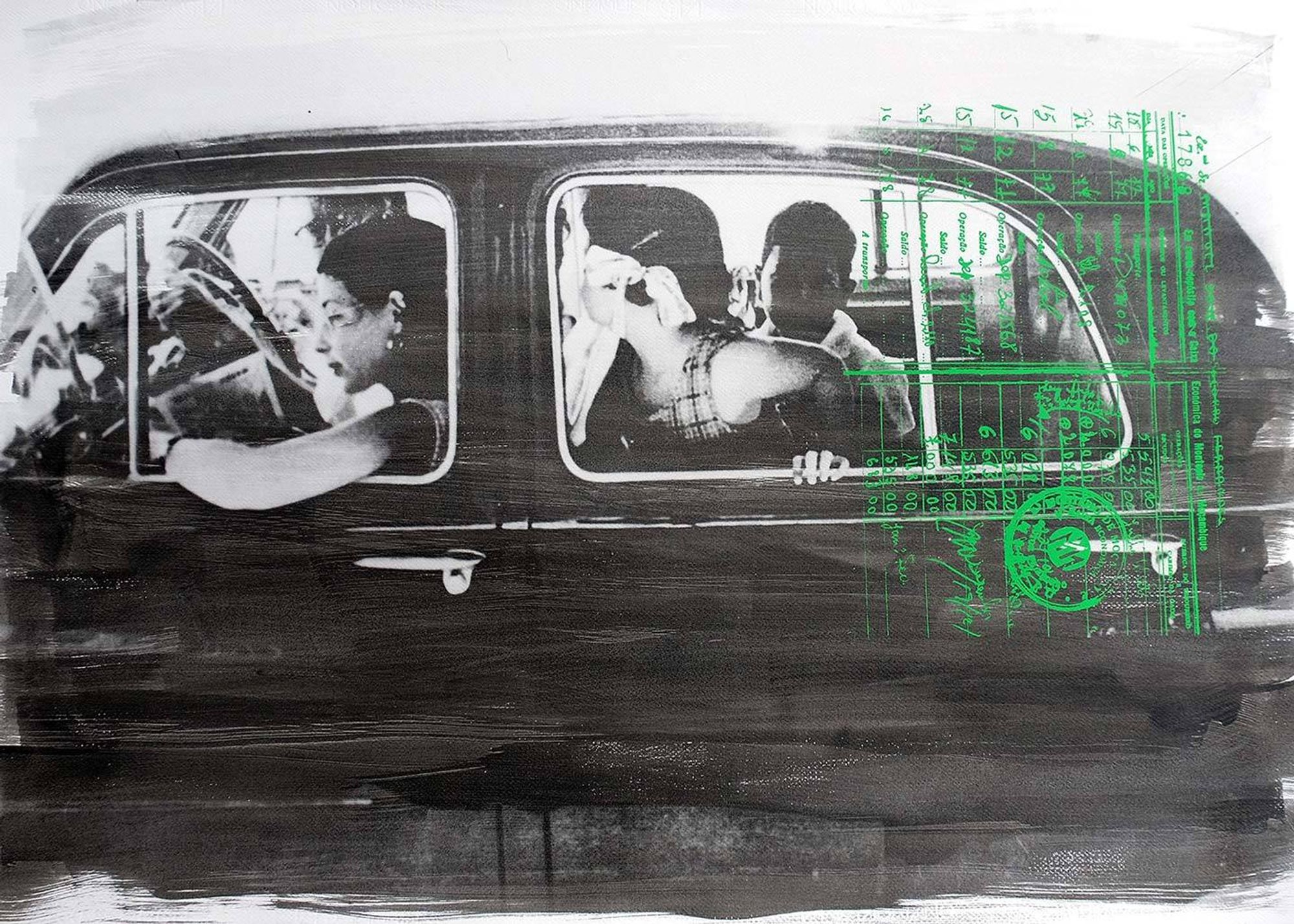

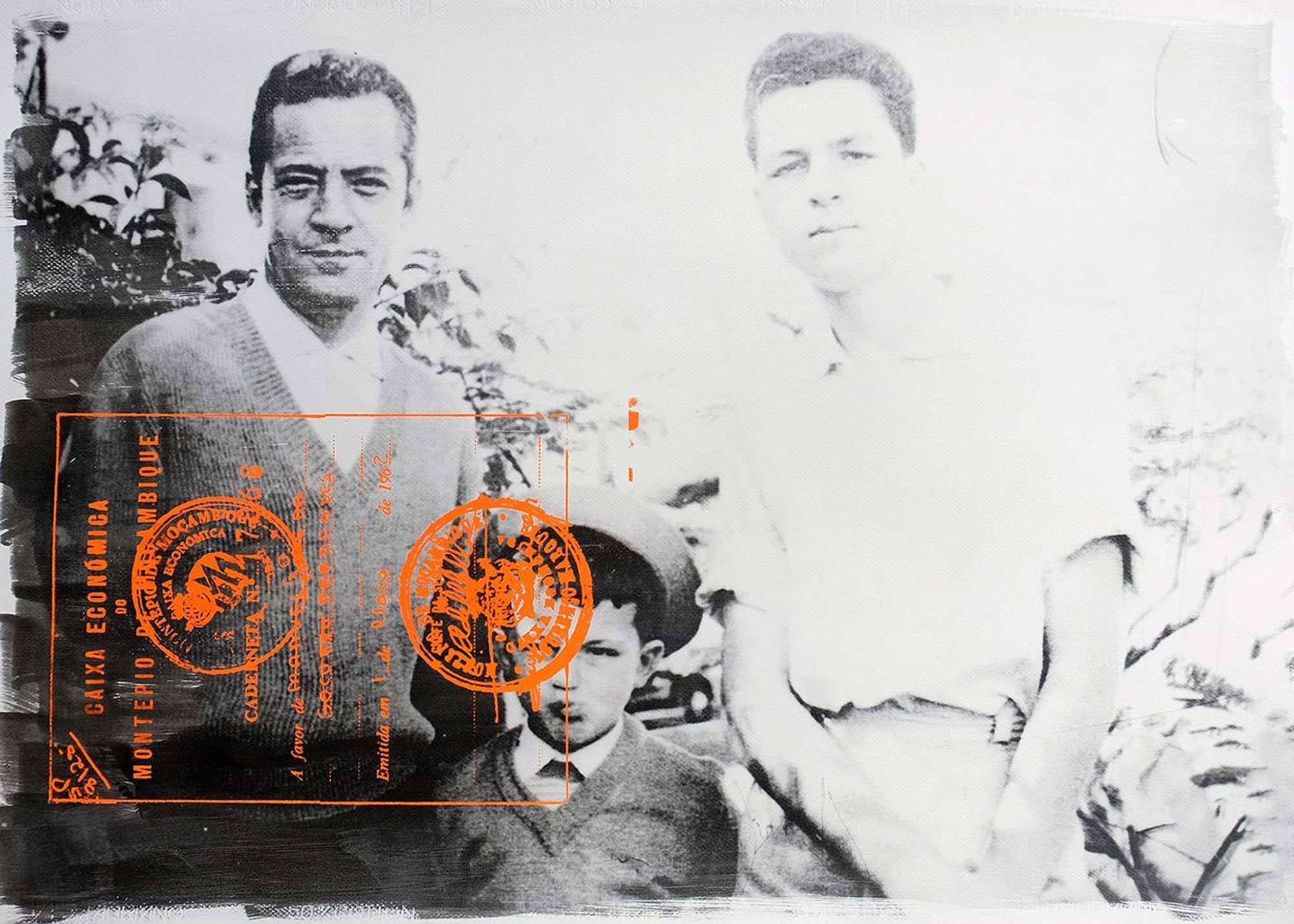

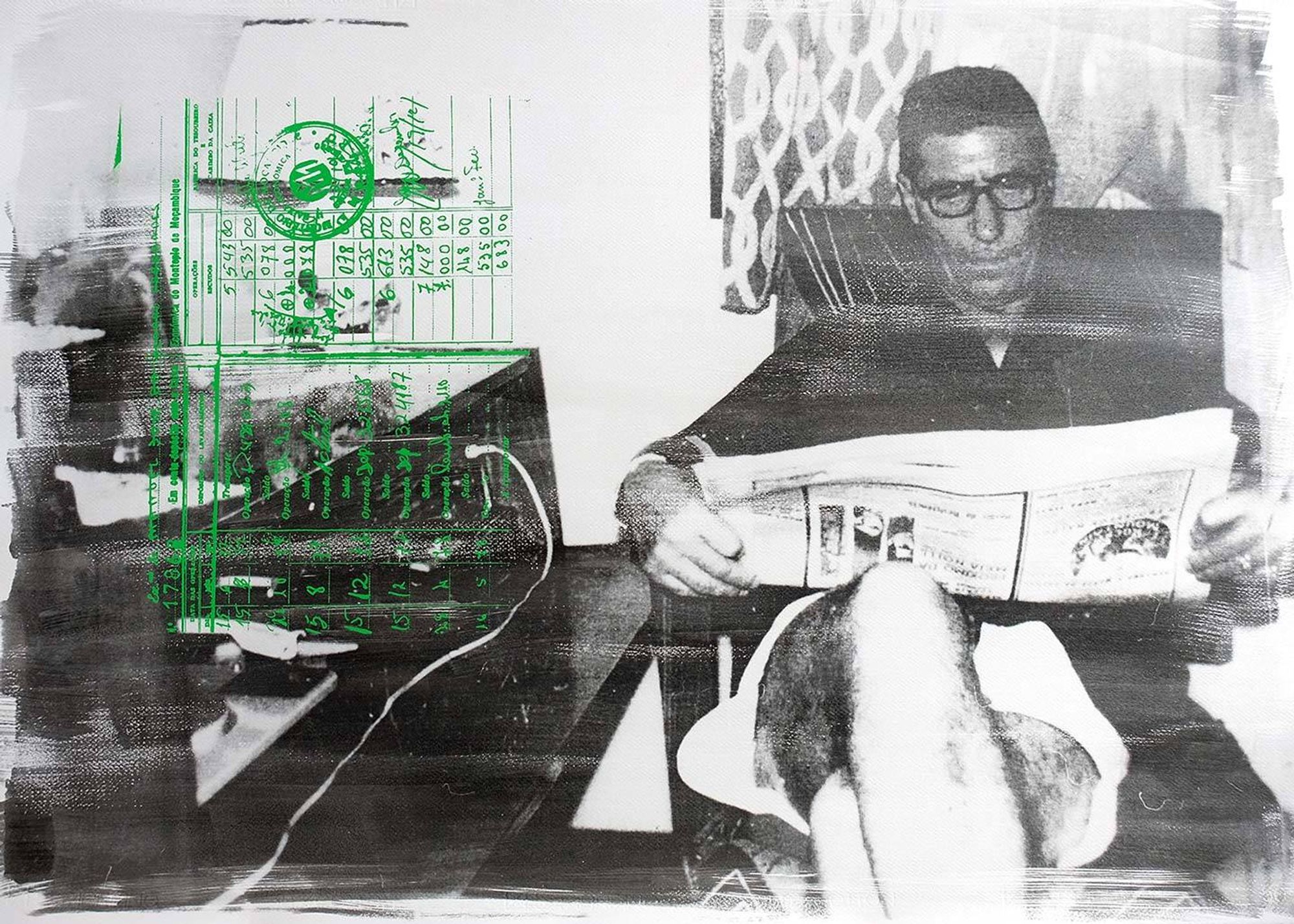

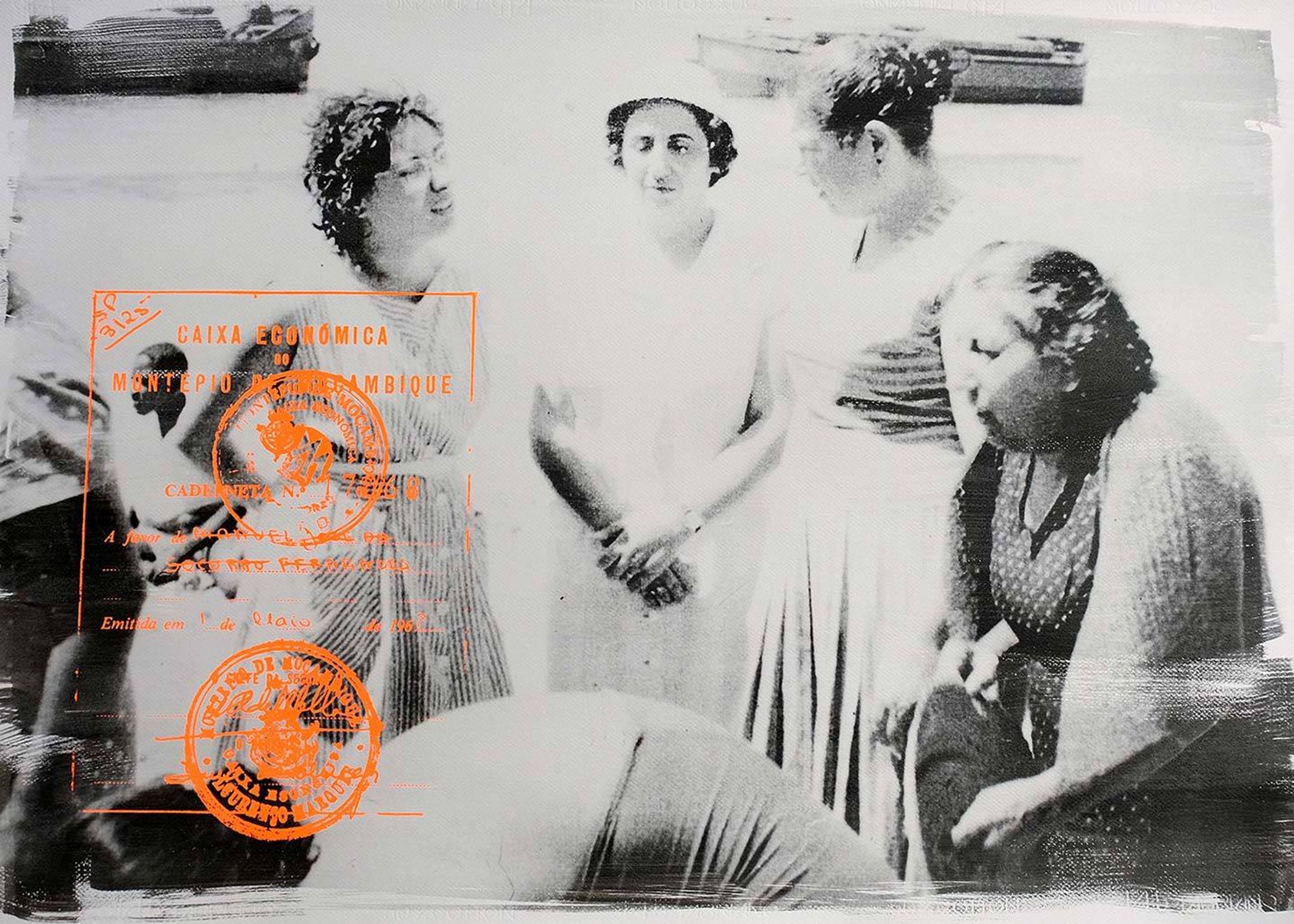

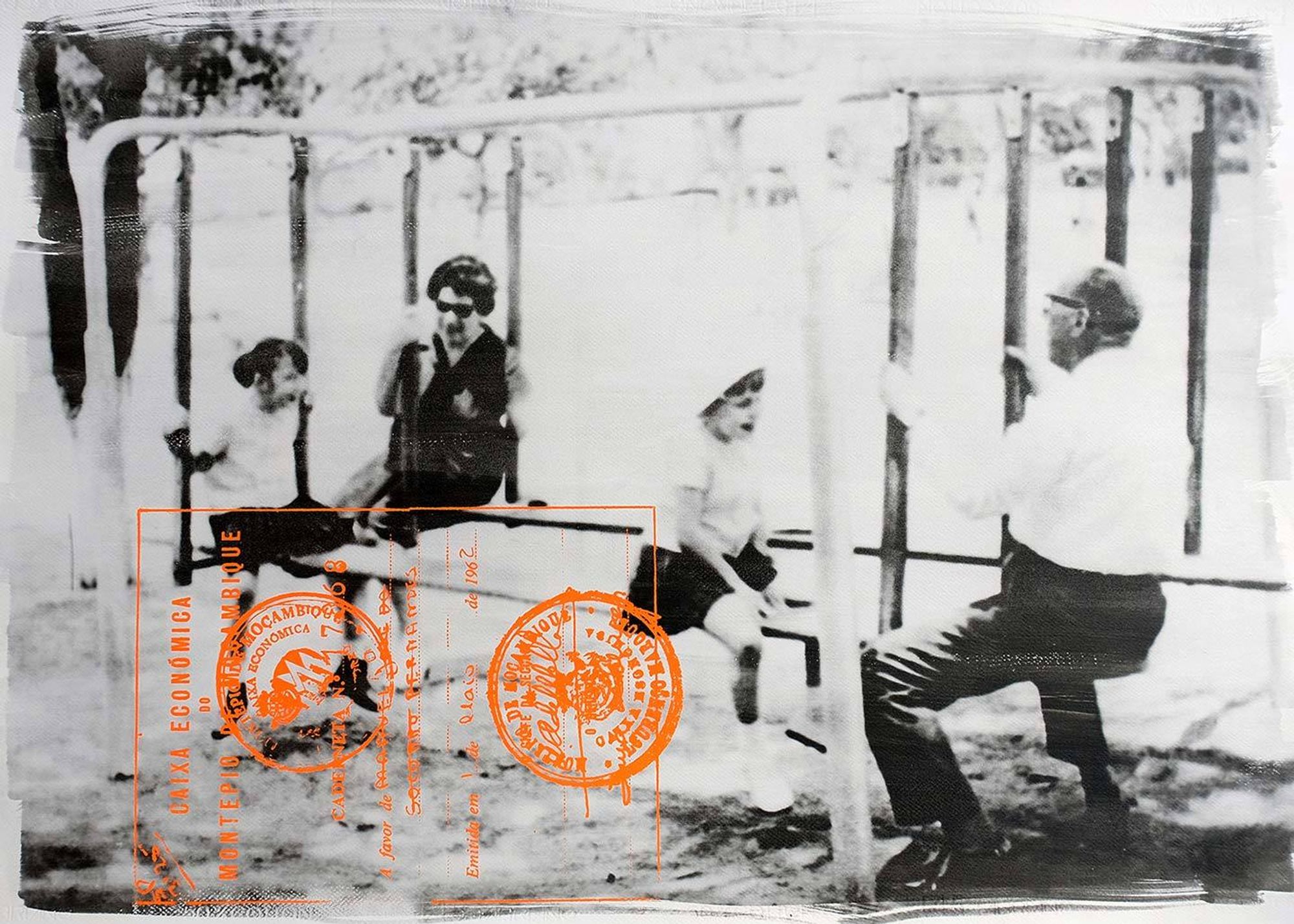

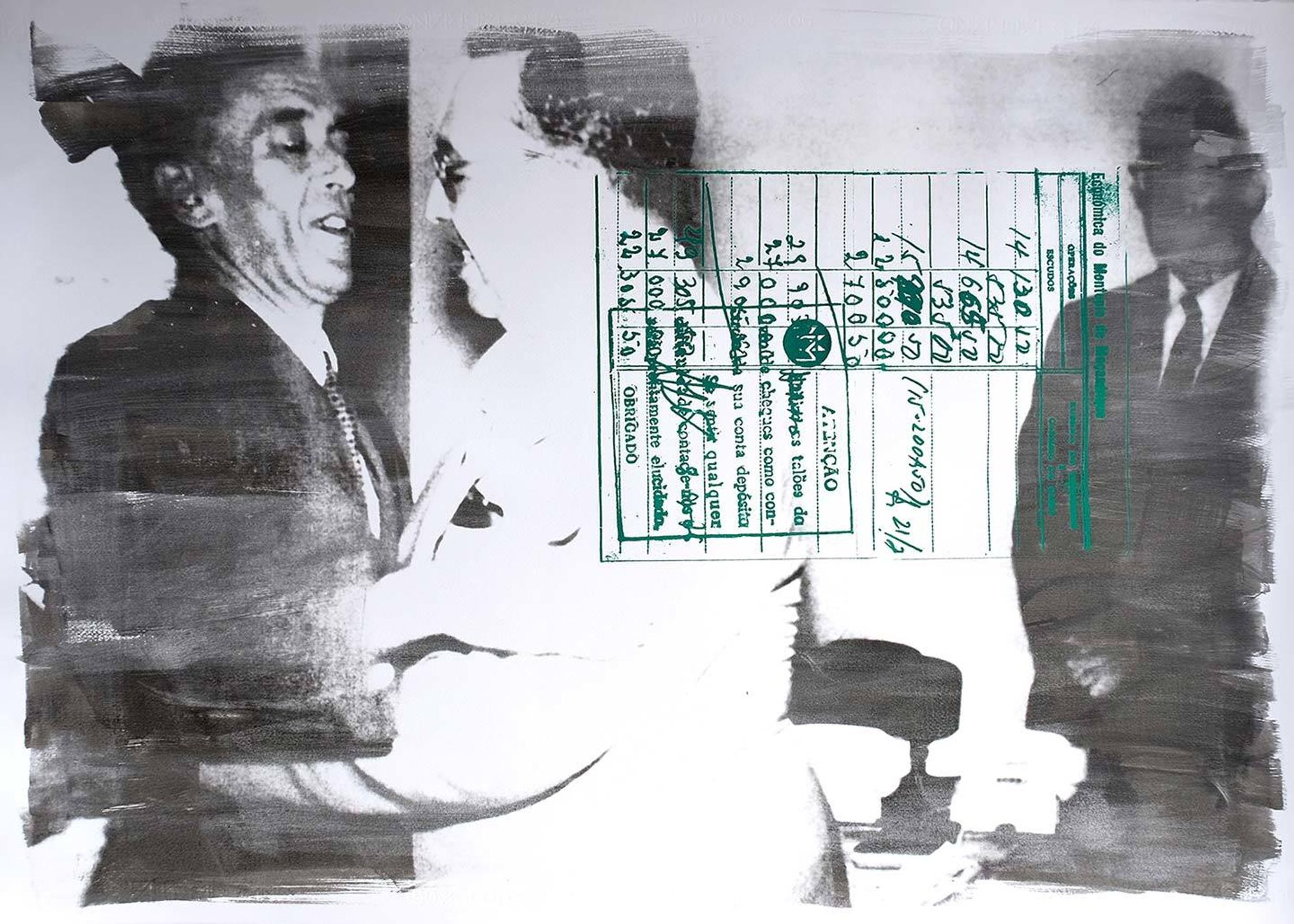

With The Lost Chapter: Nampula 1963 (2016), Délio Jasse continues his exploration of the photographic archive. While visiting a flea market in Lisbon, Jasse acquired a box of unwanted photographs which contained several dozens of prints documenting the life of a Portuguese family living in Mozambique in the 1960s. While the identity of the family remains unknown, Jasse was able, through months of archive work, to piece back together fragments of the family’s narrative, often cross referencing these with official documents – bank stamps, official government letters, personal correspondence - which shed light on some of the family’s identity and whereabouts.

Thanks to clues relating to the process of creating a photographic documentation of the family (such as stamps from the same photographic studio, a similar brand of photographic paper used throughout the photographs), Jasse was able to piece the archive together, bring together family members and reconstitute fragments of their narratives. The resulting body of work bears the traces of Jasses’ research and archiving process, as he often screen-prints atop the images, enlarged and fluo-coloured stamps lifted from the official documentation which he attributed to the family – a symbolic procedure mimicking that of a government official assigning stamps to documents and highlighting the role of photography in both, the process of memory-making in relation to the photograph but also how, since its inception, photography has been used as a tool of administrative control.

In the 1950s and 60s, the thriving colonial economy attracted thousands of new Portuguese settlers to Mozambique. Jasse’s photographs show mundane scenes of everyday life in a settler’s family: an afternoon at the beach, a birthday party, Sunday gatherings in quaint compound cottages with neat front lawns. The family’s blissful lifestyle highlights the geographies of inequality under the colonial rule, in particular the flagrant economic privilege of which the settlers benefited under the colonial regime.

Meanwhile, the absence of Mozambicans from most of the photographs, except for the few instances in which house staff of passers-by furtively appear in the frame, suggests that they were experiencing an entirely different reality. As Jasse reconstructs the family’s archive, it is the dynamics of Mozambique’s colonial past which appears ghostly, overshadowing the personal with wider historical narratives.

The Lost Chapter: Nampula 1963 raises questions around the role of the archive, in particular the role of the researcher (in this case, the artist), in interpreting the archive. A series of large double exposures directly addresses this idea, and further explores Jasse’s role as an interpreter of history. In these works, which broadly explore the notion of the metamorphosis, Jasse has created a new, fictive identity for some of the family’s members, a hybrid merging the architectural elements from their compound with their face, which alludes to the transient and imperfect nature of memory, to Jasse’s own interpretative work, ‘filling in the blanks’ and inevitably fictionalising the archive, especially where concrete information is missing, and altogether highlighting the transformative potential of the photographic archive.