Kitsigsut: The forsaken village or the eradication of the Inuit identity

-

Dates2018 - Ongoing

-

Author

Synopsis :

This body of work was taken in Greenland last September on a deserted village in the middle of the Disko Bay located on a small group of islands called Kitsigsut.

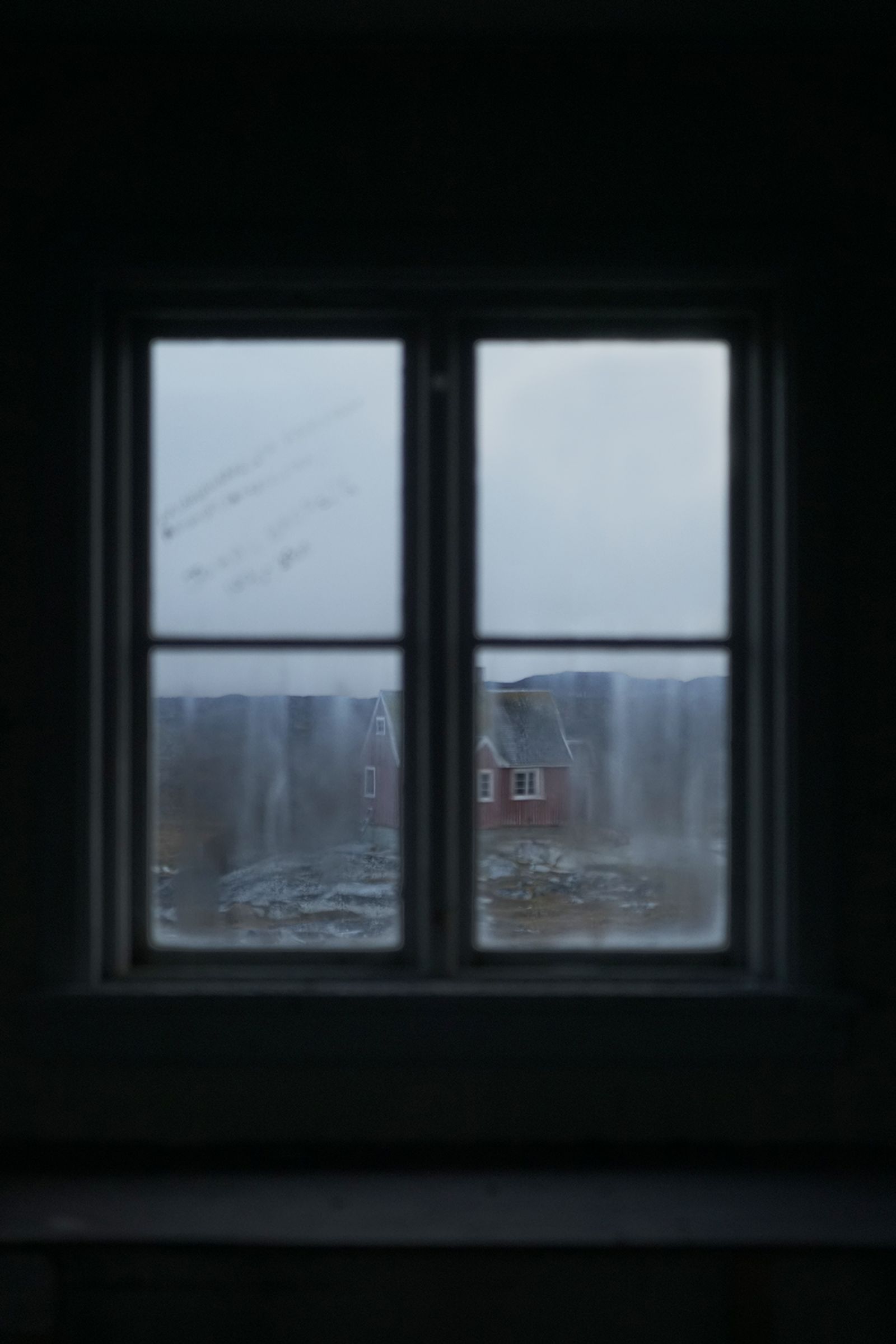

I’ve always been fascinated by abandoned places. I believe there‘s an incredible echo of poetry to those forsaken buildings. When Nature takes back its rights and takes over but that you could still imagine somewhere a child running or laughing. As if the soul of those that had once lived there had stay attached in some ways to the ground itself.

It feels as well as if the houses themselves were grieving for the people that had once lived there.

But in this case, this forsaken village appears to me as a symbol and a cruel visualisation of the lost Inuit identity. It’s not only crying out for its lost inhabitants but for the death of a way of life, for the Inuit culture and traditions that has been erased and demonized in less than a generation through the policies from the 70' and 80' (among which the closure of small villages). The Danish government decided to close this village (as dozens of others) and forced its inhabitants to move to bigger settlement where their way of life, based on collective hunting and trading of meat and skins, wouldn't make sense anymore. Today the suicide rate in Greenland is the highest in the world; it touches mainly the young ones and is linked, according to diverse analyst, to the eradication of the Inuit Identity.

.

.

.

Text:

In Greenland, between Aasiaat and Quequertarsuak, there is a small group of islands, Kitsigsut, which used to be the home of twenty or so families. After being nomads for generations, they had settled in this small piece of land in the middle of the Disko Bay living mainly of hunting and fishing. This body of work illustrate what’s left of this village today but to me, it is a representation of what happened to and what’s left of the Inuit identity and their way of life.

Years ago, the Danish government decided to close this village and forced those families to move to bigger settlement. They did so in several other small villages for obvious practical reasons: it was difficult to provide basic services like health clinics and school to every tiny village. It seems much easier to move those people to places where the infrastructure was already in place. So they just shut them down. But they did so without consideration for what those people would feel - to be torn apart from their roots-. They had to leave their traditional family home to move to concrete apartment block, with hundreds of other families from dozens of other small villages that had also been erased and where their way of life would not make sense anymore.

The identity issue is major in Greenland. From the first Greenlandic novel ever written: « A Greenlanders dream » by Mathias Storch in 1912 to more recent literature « Imaqa » by Jensen Flemming, you can feel this question raised over and over again. They used to be a proud people of hunters and fisherman. The Danish presence and influence changed that - most of all through the rapid modernisation post war and from policies of the '70s and '80s-. What used to be an honor, the most praised work a man could do – being a good hunter was a proof of both courage and skills -, became the occupation of the lower class of society. Greenlandic literature reflects over and over again a shame of being, an aspiration to the past or a renewal of lost identity.

Greenland has the highest rate of suicide in the world (In average in 2015: 82,8 suicide for 100 000 people, 6 or 7 time more than in the US for instance). It’s mainly touching the young generation. According to an article from the National public radio, it’s linked at a deeper level to the crisis of identity and Inuit’s culture: “a loss of identity that happens when a culture, in this case Inuit culture, is demonized and broken down ». When a culture is largely erased over less than a generation, as it was in Greenland, a lot of young people feel cut off from the older generations, but not really part of the new one. “It's especially difficult for young men, whose fathers and grandfathers were hunters, and who struggle to understand what it means to be an urban Inuit man”. As Musset wrote in Les confessions d’un enfant du siècle “Alors s’assit sur un monde en ruine une jeunesse soucieuse”, they had grown up in a world that didn’t exist anymore and the values they had been raised with had been erased. Like native people all around the Arctic — and all over the world — Greenlanders are seeing the deadly effects of rapid modernization and unprecedented cultural interference.

According to Anda Poulsen, interviewed by the NPR, he felt lucky as a child. He had been born in a village with great history: Kangeq, which was famous for its great hunters. It was a place people told stories about. He was proud. When his village was shut down, they had to move to apartment blocks that were supposed to be a symbol of progress. It didn’t feel that way to them. It felt foreign and lonely. ‘They was a culture clash », « there was prejudice against the people from the villages ». For Anda, they were two choices: he could stay as he was and wouldn’t de able to fit in or he could change and became a Danish speaking city kid in order to survive. At school the message was clear: Danish-speakers were better than Greenlandic-speakers; Danish stuff was cooler than Greenlandic stuff. Village kids were inferior to city kids.

In such a context, Inuit identity was bound to die. As Anda put it, he had to kill a part of himself, the village kid with all his traditions and belief, in order to survive.

I’ve always been fascinated by abandoned places. I believe there‘s an incredible echo of poetry to those forsaken buildings. When Nature takes back its rights and takes over but that you could still imagine somewhere a child running or laughing. As if the soul of those that had once lived there had stay attached in some ways to the ground itself. All human life is gone from it and yet, you can feel its presence everywhere. Any old object or trace opens the door to what used to be their lives, to the many stories that must have happened.

It feels as well as if the houses themselves were grieving for the people that had once lived there. Shadows of what they once were, they seem to cry out for the life that had left them.

But in this case, this abandoned village appears to me as the symbol of the loss of identity in Greenland. It’s not only crying out for its lost inhabitants but for the death of a way of life, for the Inuit culture and traditions that has been erased, for its identity. The fact the villagers were made to leave makes it even more so. They’ve been torn apart from their roots, they even been denied the possibility of mourning at the graveside of their loved ones and ancestors. Their way of life has been taken away. They have been forced to leave as part of those “modernisation policies” that destroyed the Inuit identity. One must wonder how much harm those forced relocations have done. If Greenlanders identity was already an issue at the beginning of the XX century with the Danish sovereignty, the death of those villages signed the death of the Inuit traditional way of life and destroyed its identity.

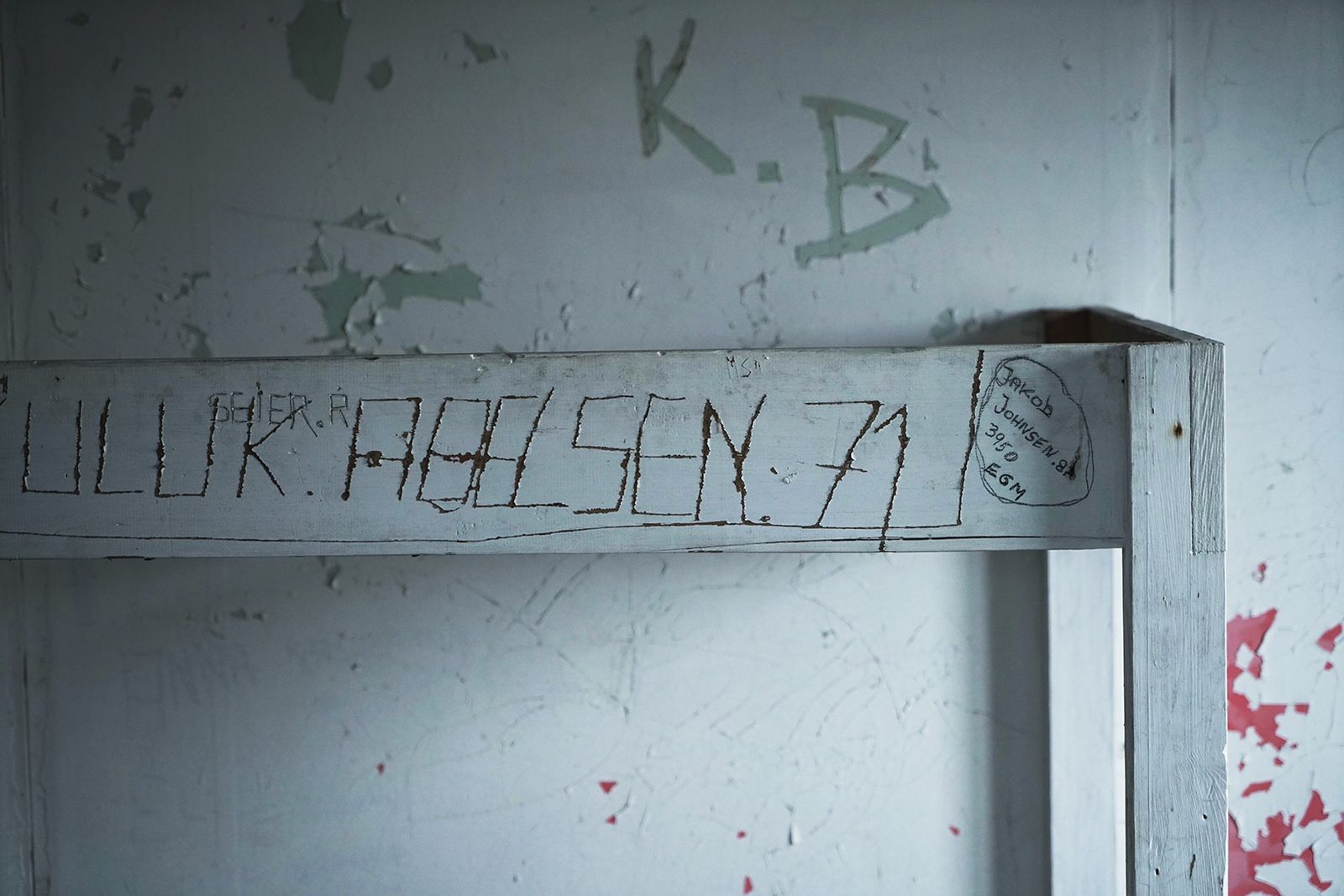

While it was still alive and filled with people it represented a way of life that was constitutive of the Inuit culture and identity and which is gone today: it was based on collective hunting and trading of meat and skins. A whale cemetery nearby indicates it used to be a good hunting place. Its inhabitants lived independently on this small island. It was a time when great tales were told about great hunter, when the villagers were proud of who they were. Looking at the stills of this forsaken village, you can still picture what it has once been. What’s left of it, the small wooden houses barely standing and sometime completely destroyed are the shadow of another era. By comparison to the town block apartment those villagers had to move in, they underline the radical difference of lifestyle they had to make. The bright colored walls, the forgotten hooks left behind testify from a way of life that has disappeared. The names and initials engraved on the wooden furniture or on the walls appear to me as a way to assert one’s identity and perhaps the Inuit one while it was being destroyed. The remains of the old school not only evoke children running around but recall the “lost generation”.

On a more general level: the actual state of the village appears to me as a cruel representation of what happened to the Inuit identity and culture; as a cruel way to visualise what is left of it today.