Cosmic Darkroom

-

Dates2014 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Guernsey, Berlin, Stockholm, Malmö

Light is pure presence. Or so it seems to our perception. But the fact that light has a specific velocity, i.e., it is not everywhere simultaneously, contradicts direct experience—because we cannot see that the sun’s brilliance is eight minutes old when it arrives on earth, or that even pale moonshine requires a full 1.3 seconds before reaching the human retina. At the moment we look at them, the heavenly bodies are— depending on their distance from earth—already minutes, years or millions of years older than the presence of their image. And this is a valid principle: light temporalizes images, which is alien to our vision, however. Johan Österholm’s artistic research interest starts out from this difference. As a photo artist, he is a kind of light historian; using photography as a medium of reflection with which to make the spatio-temporality inscribed into light aesthetically tangible and comprehensible. Formally, he adopts different approaches and modes of depiction, but cosmological and civilisatory aspects are always interwoven in them.

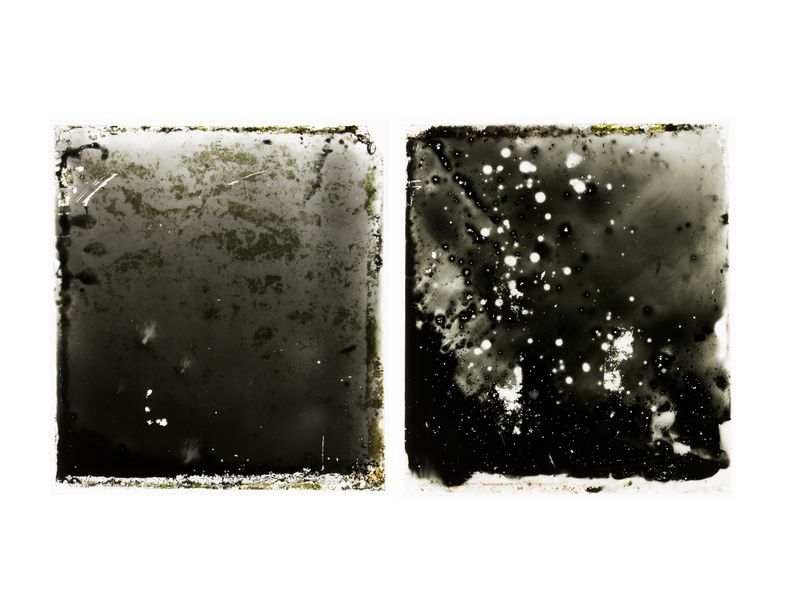

During his stay at Künstlerhaus Bethanien (in 2018), for example, he researched into the history of Berlin observatories in the context of the introduction of street lighting, which contributed decisively to the fading of the night skies over the big city. And so he was fascinated by the story of the “Neue Berliner Sternwarte” (“New Observatory Berlin”), which was constructed at the corner of Lindenstraße/Friedrich- straße in 1835. It was here that the planet Neptune was discovered in 1846. Over the course of universal electrification and the increasing prevalence of street lighting, however, its operations came to a standstill; the building was demolished in 1913 and the institute moved to Potsdam. There are apartment buildings on the original site today. Österholm responds artistically to the historical context in a kind of reverse manoeuvre: while urban illumination means that the night sky is beyond recognition, the artist uses the light fitting of a street lamp acquired especially for the purpose to make analogue prints from historical negatives in his studio, which picture stellar constellations in their turn (and intends in future to make some prints outside in the streets as well). Photos from the work group Antique Skies (2018–), for example, reproduce such sections of the night sky that have become invisible to the naked eye as a result of light pollution today. These are hand-produced prints made using a complicated process; the artist uses archive negatives produced in Berlin and Hamburg between 1880 and 1910 and exposes them with the help of the aforementioned street lamp—not onto traditional photo paper but onto pages torn from 19th century books about astronomy, prepared using a light-sensitive emulsion. A related group of works is Untitled Lantern Piece (2018–), for which Österholm produced prints from historical negatives of the night sky onto glass plates recalling the shape and dimensions of those found in old gas lanterns, which he also prepares with photographic emulsion.

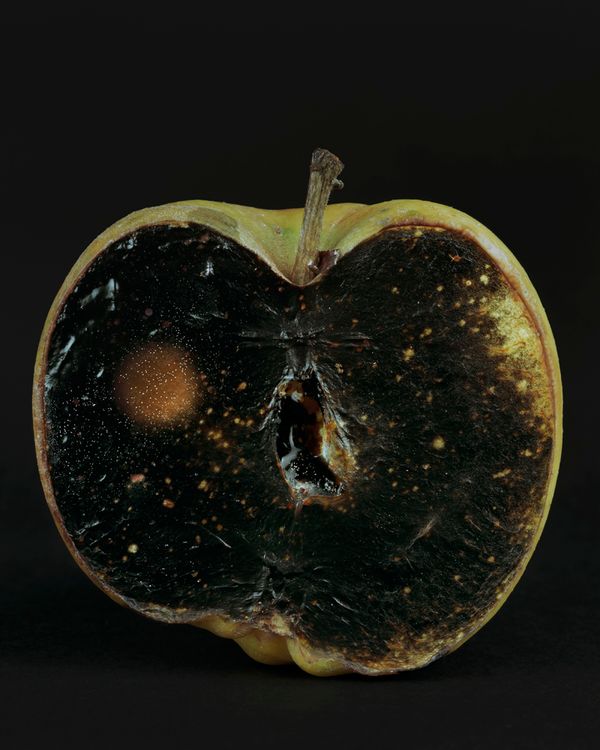

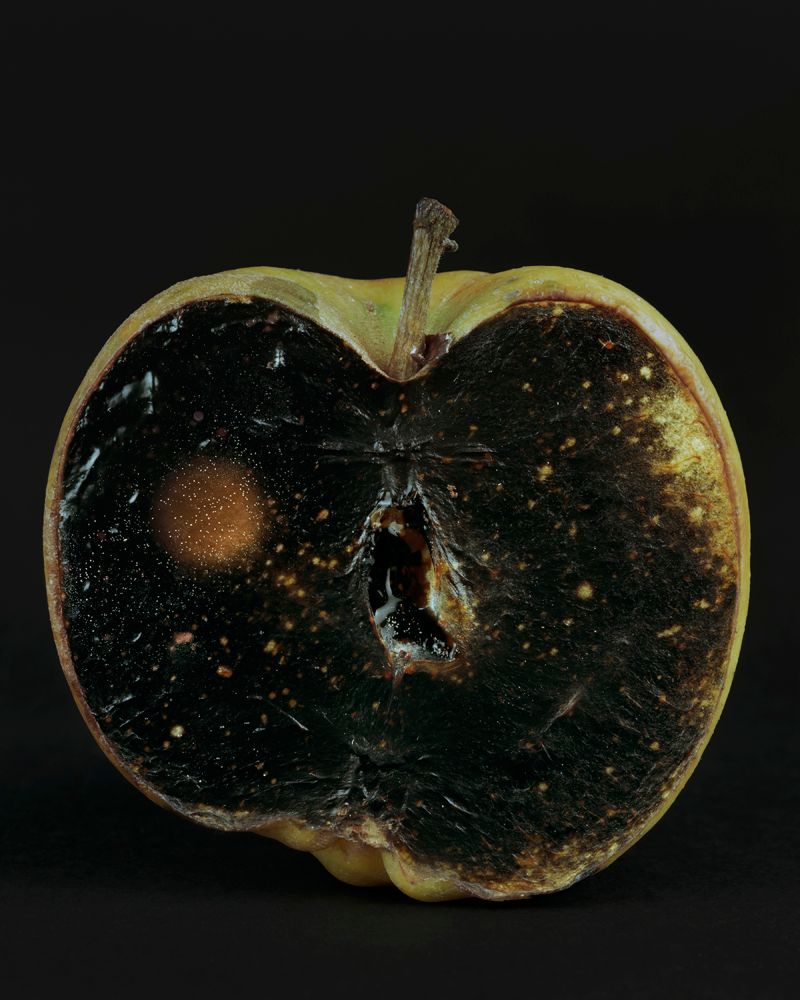

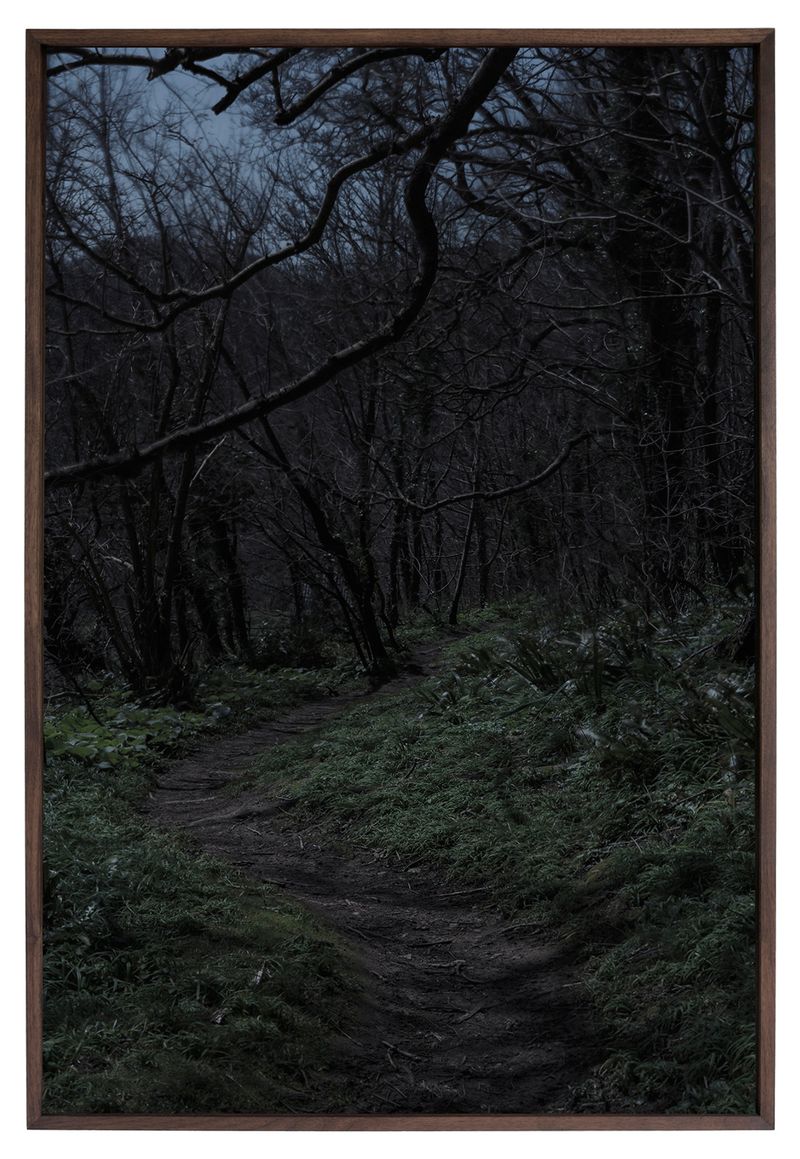

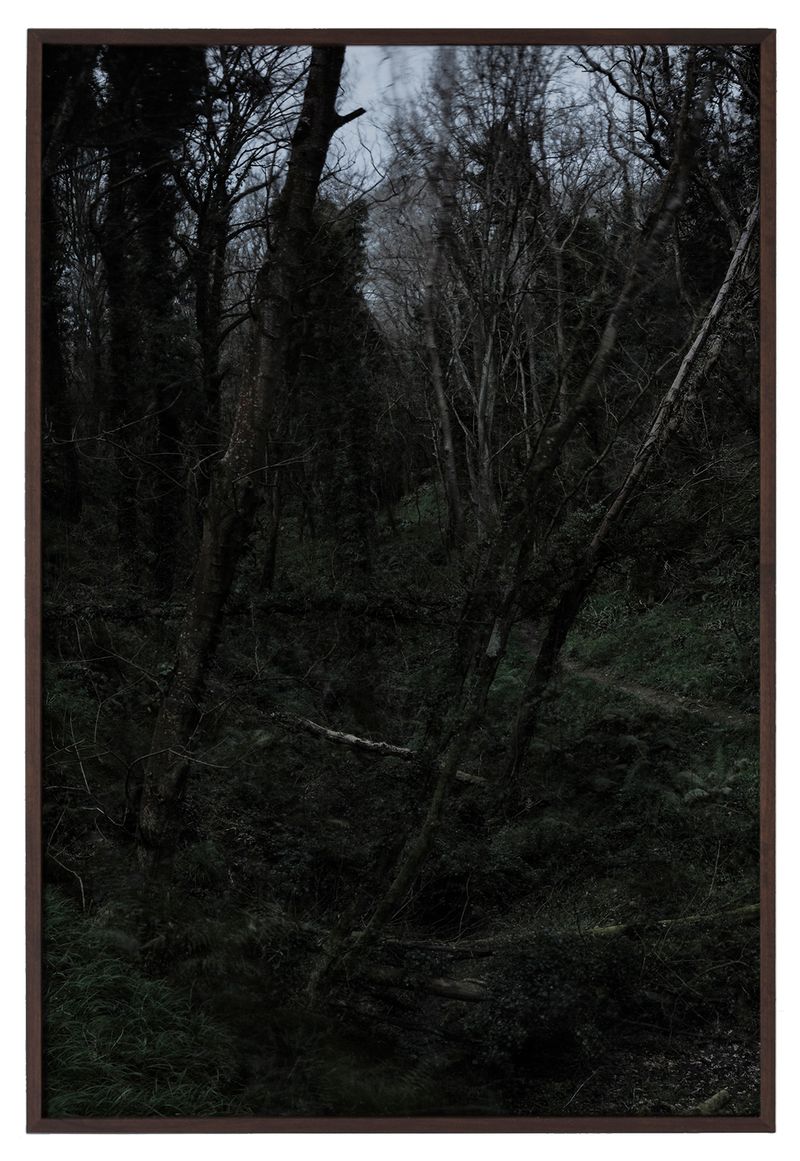

The theme is also present, albeit differently, in Some Moon Walks (Isle of Sark) (2017): Österholm spent several days on this particular Channel Island, a “crown dependency” of the British royal house, which received an award from the International Dark-sky Association in 2011 as the first dark sky island world-wide. There is neither public lighting nor traffic there, and the sea swallows the light from the neighbouring islands of Guernsey and Jersey. Sark has the “cleanest” night sky in Europe. For half a lunar cycle (from new moon to full moon) the artist went walking at night across the island, taking land- scape photos in the moonlight using long exposure times (incl. Some Moon Walks (Winding Path), 2017). There, he also exposed glass plates covered in emulsion to capture moonlight directly. The photographic work Moon Plate Exposing (Isle of Sark) (2017) reproduces an impression of the process—which Österholm had also applied similarly in Structure for Moon Plates and Moon Shards (2015). For this, he took glass panels and broken pieces from an old greenhouse, painted them over with silver gelatin emulsion and subsequently exposed them to moonlight. Then, he reassembled the developed glass plates into a hut-like, open structure—and so created the dark-side version of a light, sun-flooded greenhouse. The lively irregular black is a result of applying the emulsion by hand, so that the work also involves an aspect of light-painting.

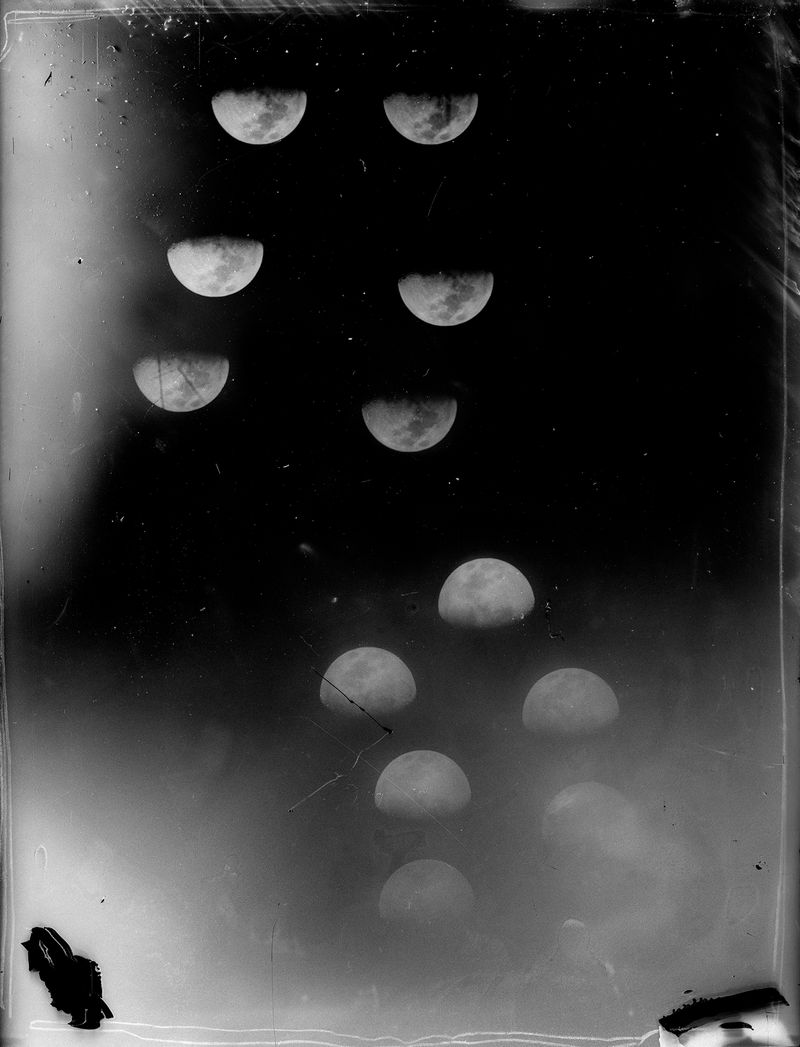

Österholm’s fascination with the cosmic dimensions of light is also connected to his biography. This is demonstrated in Lunar Year (1930s/2015), for example, the silver gelatin print of a glass negative showing the moon in twelvefold exposure. The negative came from Österholm’s great-grandfather, who also devoted himself to the night sky in photography, and from whom he inherited an archive. Originally, the motif was probably a series testing various expo- sure times. But Österholm also brings home to us its poetic-suggestive beauty with his print made over eighty years later. Homage to his ancestor—and to the moon, the light of which outshines and yet connects both their lifetimes.

Text by Jens Asthoff for (Künstlerhaus Bethanien) BE Magazine 25.